The motivation to study health services is to discover things that will help improve health care. Yet most research papers are rarely read, few are cited, and very few directly influence the policy decisions that they are meant to inform. How can we — the discipline of health services research — get our data out of the journals and into the public square?

Articles in specialist journals are largely inaccessible to non-specialists, even other scientists. The field needs translators, great researcher/writers like Atul Gawande, who can take research findings and restate them in a way that connect the data to the concerns of the educated lay reader.

So how do we get more translators?

Perhaps everyone could become his or her own translator, writing about their research on blogs and other social media. This proposal, however, collides with the contempt many researchers hold for social media. David Grande and his colleagues (including the physician/writer Zach Meisel) surveyed researchers about their perceptions of social media:

Researchers described social media as being incompatible with research, of high risk professionally, of uncertain efficacy, and an unfamiliar technology that they did not know how to use.

Other than that, they liked social media just fine.

Many of the respondents to Grande’s survey are likely right about whether they should blog. Writing for non-scientists requires skills that not everyone has. Even for the talented, it takes significant time to blog well. Blogging can have career benefits if you succeed in a big way, but few writers do. On Twitter, Don Taylor (@donaldtaylorjr) advised researchers to

focus on your comparative advantage. Constantly re-evaluate if the time spent is worth it. Not blogging should be your default choice.

If you are expert in quantitative methods and just okay as writer, you and we will be better off if you focus on methodologically intensive research, perhaps teaming up with colleagues who can help write the papers.

Nevertheless, there are potential Atul Gawandes out there, people with a latent comparative advantage in translational writing. How can we help them flourish?

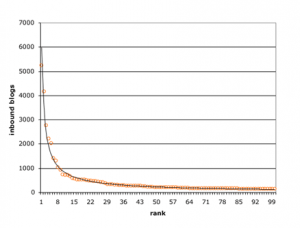

The biggest obstacle I found in blogging was finding an audience. Months of disciplined writing brought only a trickle of page views, until my work started getting recommended by other writers. The distribution of blogging audiences roughly follows a power law. A few top rank bloggers have a huge audience, but readership falls off precipitously, and the beginning blogger is way out on the long right hand tail of people with almost no audience. Similarly the median Twitter user has just a handful of followers. It bothers you that no one reads your articles? No one will read your blog either. And if you do not get readers, however well you write, you will not translate and disseminate science.

So what the health services discipline should do is help writers build their audiences. People select things to read based on the recommendations of trusted others: it doesn’t matter whether we are talking about John Grisham or the NEJM. Traditionally, people have gotten cues about what scientific articles to read in seminar, at the lunch table, or by following a reference in a text. Today, however, people are getting cues to good reads from links shared on social media.

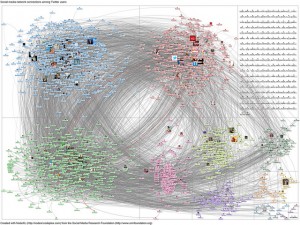

The first step to building the audience for translational writing is to grow the social media network of those who produce and consume health services research. We need a large, highly connected social graph of colleagues discussing the field, contributing links to articles, and retweeting good links. The velocity of dissemination of a link to an article is an increasing function of the extent of the network, the density of network interconnections, and the intensity of participation of network members. If links to good blog posts and journal articles start reaching more people faster, it will become easier for new translational writers to build an audience and find the reinforcement to sustain their efforts. As the translational literature grows, the connections between our network and journalists and policy intellectuals will grow. This will accelerate the diffusion of research out of our journals and meetings, and into the world.

So, then, how do we grow the social graph of health services research? Grande and his colleagues note that

Researchers will need evidence-based strategies, training, and institutional resources to use social media to communicate evidence.

Here are a few ideas. There are strategies for using Twitter efficiently and productively. AcademyHealth and similar groups could put together a brief guide and disseminate it. Social network analysis tools could be used to learn who the highly connected health services researchers are. These are the handles that novice users should follow and they could be provided to them as suggestions. A Twitter account could be established that provides links to new articles and blog posts of interest.

Despite the pessimism about social media documented by Grande and colleagues, there are many reasons for optimism. We all know that the future of research is on the network.