From the American Journal of Public Health, “Dentist Supply and Children’s Oral Health in the United States“:

Objectives. We evaluated the relationship between dentist supply and children’s oral health and explored heterogeneity by children’s age and urbanicity.

Methods. We obtained data from the 2007 National Survey of Children’s Health (> 27 000 children aged 1–10 years; > 23 000 children aged 11–17 years). We estimated the association between state-level dentist supply and multiple measures of children’s oral health using regression analysis adjusting for several child, family, and population-level characteristics.

We always talk about the “doc shortage” in the US, but sometimes we don’t spend enough time talking about dentists. Although fluoride has made a difference, cavities are still the most common chronic disease of childhood. Dental health is still a real issue.

This study examined the relationship between the number of dentists at a state level and different metrics of oral health in children. And, before you ask, they controlled for the following:

child’s gender, race/ethnicity, country of birth (United States vs others), numbers of children and adults in the household, and maternal age and marital status. We included the following household socioeconomic characteristics: maternal education, household income relative to federal poverty level (according to the Department of Health and Human Services’ federal poverty guidelines for 2007), and child’s health insurance coverage. We also included measures of various aspects of the neighborhood where the child lived, including physical condition (presence of litter or garbage, poorly kept or rundown housing, and availability of a library or bookmobile), safety (presence of vandalism and maternal perception of child’s safety), and social capital (people in the neighborhood helping each other, watching out for each other’s children, and counting on each other, and adults helping children if they are hurt or scared).

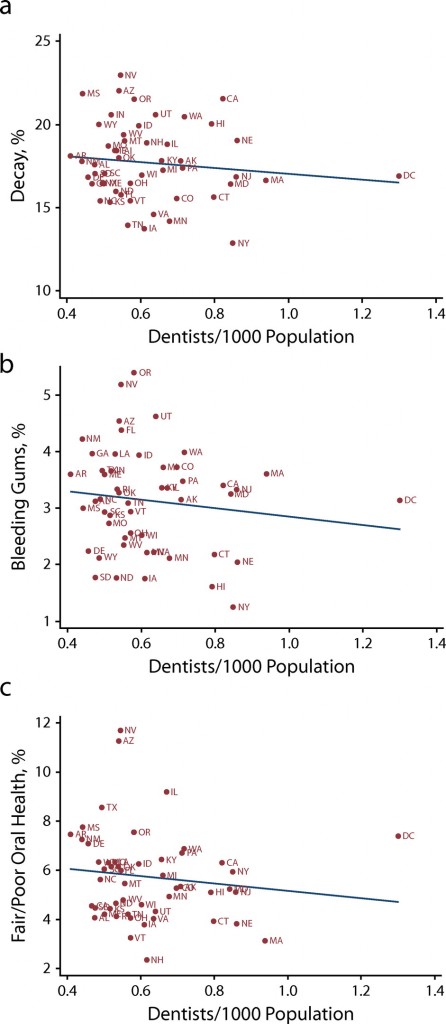

What did they find? Dentist supply was significantly associated with a lot. For each additional dentist per 1000 population, the odds of decay in kids’ teeth halved, and the odds of kids’ having bleeding gums went down 80%. More:

Yes, this is state-level aggregation. Yes, this association was only robust for children in urban areas. Yes, it’s observational data. But we spend so much time ignoring dental health in exchange for “medical” health. This is part of “health”. It shouldn’t be minimized.