The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2014, The New York Times Company).

For years, we have known that diets high in salt can be bad for people with high blood pressure. A study published recently in The New England Journal of Medicine confirmed this fact. It monitored more than 100,000 people in 18 countries and found that people who consumed more sodium generally had significantly higher blood pressures than those who did not.

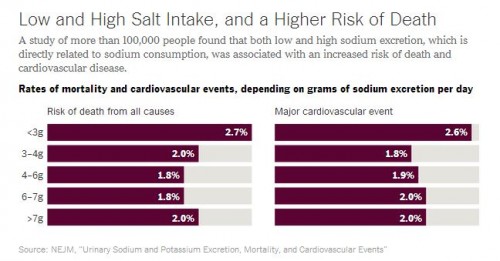

Another manuscript in the same journal looking at the same study population went even further. It found that people who consumed more than 7 grams of sodium per day had a significantly higher chance of death than people who ate 3-6 grams per day. People consuming high levels of sodium had higher rates of heart attacks, heart failures and strokes as well.

These results confirm that people who eat too much salt should eat less of it. The problem with the way we respond to such information, though, is that we often run too far and too fast in the other direction.

Americans consume, on average, 3.4 grams of sodium per day, or about the equivalent of three and a half tablespoons of soy sauce. This is on the low end of the “safe zone” of 3-6 grams in the study. The United States Food and Drug Administration thinks that’s not low enough. It recommends 2.3 grams per day. The World Health Organization says it should be 2.0 grams. The American Heart Association goes even further and recommends we consume no more than 1.5 grams.

Why? There’s surprisingly little rationale for this belief. Last year, experts convened by the Institute of Medicine assessed the evidence concerning sodium intake around the world. They agreed that efforts to reduce excessive sodium were warranted. But they cautioned that no such evidence existed to recommend a very low salt diet. They hoped that future research would assess the potential benefits of a diet where sodium intake was 1.5 to 2.3 grams per day.

The second New England Journal of Medicine study did just that. In addition to looking at high sodium diets, it compared the health outcomes of those who had very low sodium diets. What they found was worrisome. When compared with those who consumed 3-6 grams per day, people who consumed less than 3 grams of sodium per day had an even higher risk of death or cardiovascular incidents than those who consumed more than 7 grams per day.

This result would be shocking if we in the medical community hadn’t seen it before. But we have. In 2011, researchers published a study in the Journal of the American Medical Asssociation after following 3,681 people over almost a decade. They, too, found that excessive salt intake was associated with high blood pressure. They also found that a low-sodium diet was associated with higher mortality from cardiovascular causes.

Why experts and organizations feel the need to go from one extreme to the other is unclear. But it’s unfortunately something we do far too often in medicine.

Take cholesterol. Initially, people believed that the evidence was pretty compelling that high cholesterol was bad for you. But instead of focusing on those who are really at high risk, or those at the very highest ranges of cholesterol levels, we saw recommendations emerge that told us that all cholesterol was bad. We began to eliminate it from our diets completely. Eggs were shunned.

But later research showed us that egg consumption had no relationship to cardiovascular disease for most people. In fact, a majority of people’s serum cholesterol level has little to do with how much cholesterol is in their diet.

Today we use medications to lower our cholesterol levels. Once again, though, our sights keep shifting lower. Instead of focusing on those who are most at risk, we’ve decided cholesterol is so unhealthy that a 60-year-old African-American man with a total cholesterol of 150 might be placed on therapy. Just two years ago, a total cholesterol level of 200-239 was considered to be a definition of “intermediate” cardiovascular health. Theaverage total cholesterol value in America is 200.

This problem doesn’t run solely in the direction of eradication, though. It’s well understood that vitamin deficiencies can lead to significant diseases. Our response has often been to take them in ever increasing megadoses. There’s no evidence that this does any good, and some vitamins can actually harm usif we consume too much of them.

More often than not, though, the body can’t use the extra vitamins, and just gets rid of them. The truth is that vitamin megadoses mostly just createvery expensive urine.

Too many calories are bad for us. That doesn’t mean we should consume none. Too little exercise can lead to bad outcomes. That doesn’t mean you exercise to the point of hurting yourself. Too much sun can cause cancer. That doesn’t mean we should never go outside.

It’s a cliché but true: In so many things moderation is our best bet. We have to learn that when one extreme is detrimental, it doesn’t mean the opposite is our safest course. It’s time to acknowledge that we may be going too far with many of our recommendations.