The following is a slightly edited excerpt from the working paper version of my paper “How much do hospitals cost shift? A review of the evidence,” to appear in issue 1, volume 89 of The Milbank Quarterly (expected March 2011). See also “Estimating Hospital Cost Shift Rates:A Practitioners’ Guide“.

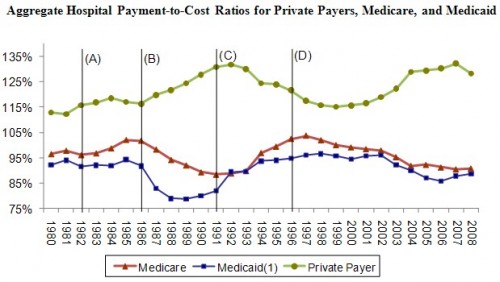

Yesterday, I explained the features of the following figure through 1991. Today, I’ll tell the story of the (more) modern era. (Figure sources: AHA (2003, 2010)). Before I get into it, make sure you’ve read my post on Monday for the definition of “cost shifting.”

The Ascendency of Managed Care (1992-1997)

The role of market power in price setting is made crystal clear by considering the experience of the 1990s (between lines (C) and (D) of the figure). The business community, desperate to put an end to the annual double-digit percent increases in premiums, changed course, removing traditional indemnity plans from their offerings and encouraging the growth of managed care. Managed care plans covered the majority of private plan enrollees beginning in 1993 (51%) and grew rapidly thereafter, capturing 70% of the market by 1995 (Mayes 2004). Robert Winters, head of the Business Roundtable’s Health Care Task Force from 1988 to 1994, said,

What happened in the late 1980s and in the early 1990s, was that health care costs became such a significant part of corporate budgets that they attracted the very significant scrutiny of CEOs. . . . More and more CEO’s [were] saying, ‘Goddammit, this has to stop!’ (Mayes 2004)

What stopped it was network-based contracting. The willingness for plans and their employer sponsors to exclude certain hospitals from their networks enhanced plans’ negotiating position. To be accepted into their networks, hospitals had to negotiate with plans on price. The balance of hospital-plan market power shifted, resulting in the 1992-1997 downward private payment-to-cost ratio trend illustrated in the figure.

By contrast, payment-to-cost ratios for public payers grew in the early 1990s. This isn’t a (reverse) cost shifting story, however, because there is no evidence that public payments increased in response to decreasing private ones. Instead, the dynamics are better explained by changes in cost. Guterman, Ashby, and Greene (1996) report that growth rates of hospital costs declined dramatically in the early 1990s, from above 8% in 1990 to below 2% by mid-decade, perhaps due to the pressures of managed care, a point echoed and empirically substantiated by Cutler (1998). The rise of hospital costs continued at low rates through the 1990s, averaging just 1.6% per year between 1994 and 1997. By contrast, Medicare payments per beneficiary to hospitals, which had been partially delinked from costs under the PPS, increased 4.7% per year (Mayes and Hurley 2006). That the movements in the time series of Figure 1 confound the effects of price and cost is a second way—along with obscuring market power effects—they give a false impression of large, pervasive cost shifting. Put simply, there are many ways for public and private payment-to-cost ratios to change and the causal connection between prices (cost shifting) is just one of them.

The Managed Care Backlash and the BBA (1997-2008)

With so much room for costs to fall, managed care plans profited relatively easily for several years, negotiating with hospitals to accept lower payment increases and reducing hospital use among subscribers (Reinhardt 1999). Plan profitability fell throughout the 1990s, however, as price competition among plans squeezed inefficiencies and surplus from the system. In an attempt to maintain profitability, plans imposed greater restrictions on enrollees, subjecting them to more stringent utilization reviews, tighter networks, elimination of coverage for certain services, and higher cost sharing (Rice 1999, Mayes and Hurley 2006).

These cost-saving measures became increasingly unpopular and a managed care backlash ensued. States and the federal government enacted managed care reform and consumer protection laws (Sorian and Feder 1999). By 1997 the era of managed care’s strong restraints on cost had ended and with it the low premium increases they delivered earlier in the decade. America entered the current age of health care plans, in which less restrictive network contracting embodied in the preferred provider organization (PPO) became the norm. Plans and hospitals still negotiate on price, but with consumers disliking restrictions on choice of providers, leverage shifted away from plans and toward hospitals. Reinforcing this shift, hospital mergers increased in the late 1990s (Vogt 2009). By the turn of the century, private payment-to-cost margins began to increase.

Coincidental with popular rejection of managed care, Congress turned its attention to the budget deficit and again sought savings from Medicare. The 1997 Balanced Budget Act (BBA) was enacted, promising $115 billion in Medicare savings over the 1998-2002 period by eliminating retrospective cost-reimbursement for post-acute care, long-term hospital services and for hospital outpatient departments (Wu 2009). Thus, hospital Medicare payment-to-cost ratios declined as those of private payers increased, but perhaps only coincidentally. The latter was facilitated by a shift in market power, the former by policy change. The extent to which they are causally related cannot be determined from the figure alone.

In summary, the figure reveals a negative correlation between public and private payment-to-cost ratios since 1985. This suggests cost-shifting but doesn’t prove it. Other hypotheses are consistent with the evidence. Historical changes in hospital costs and the balance of market power between hospitals and plans may explain all or some of the data. Only careful empirical analysis can reveal the causal effect of public prices on private ones, free of the confounding effects of changes in market power and hospital practices that impact costs. In my paper, I review such analysis. Want to know what I find? Regular readers of this blog already know. The details are in the paper.

Next week I’ll cover cost shifting theory in greater detail.

References

Cutler D. 1998. Cost Shifting or Cost Cutting? The Incidence of Reductions in Medicare Payments. Tax Policy and the Economy 12:1-27.

Guterman S, Ashby J, and Greene T. 1996. Hospital Cost Growth Down: Unprecedented Cost Constraint by Hospitals Has Maintained Their Bottom Line. But Can It Continue? Health Affairs 15.

Mayes R. 2004. Causal Chains and Cost Shifting: How Medicare’s Rescue Inadvertently Triggered the Managed-Care Revolution. Journal of Policy History 16:144-174.

Mayes R and Hurley R. 2006. Pursuing cost containment in a pluralistic payer environment: from the aftermath of Clinton’s failure at health care reform to the Balanced Budget Act of 1997. Health Economics, Policy and Law 1:237–261.

Reinhardt U. 1999. The predictable managed care Kvetch on the rocky road from adolescence to adulthood. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 24(5): 897-910.

Rice T. 1999. The microregulation of the health care marketplace. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 24(5):967-972.

Sorian R and Feder J. 1999. Why we need a patients’ Bill of Rights. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 24(5):1137-1144.

Vogt W. 2009. Hospital Market Consolidation: Trends and Consequences. National Institute for Health Care Management. Expert Voices. November.

Wu V. 2009. Hospital cost shifting revisited: new evidence from the Balanced Budget Act of 1997. Int J Health Care Finance Econ. Published online 12 August 2009.