We all need 8 hours of sleep per night for good health, right?. And the more sleep we get, the better health we’ll enjoy, yes? It turns out the evidence doesn’t support either claim. The optimal sleep length may be closer to 7 hours than 8, and it may be worse to sleep more than 7 hours than it is to sleep less than that amount.

In “Sleep duration and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis,” Lisa Gallicchio and Bindu Kalesan conducted a review of

23 prospective cohort studies that examined the associations between sleep duration and all-cause and ⁄ or cause-specific mortality. Findings from the quantitative analyses indicate that among both males and females, short sleepers and long sleepers are at increased risk for all-cause mortality compared to individuals who report, on average, a medium amount of sleep per night (generally defined as 7 to 7.9 h).

In fact, the pooled relative risks for all-cause mortality, as well as cardiovascular- and cancer-related mortality, was higher for long sleepers than short sleepers, relative to those who slept between 7 and 8 hours.* So sleeping longer may, in fact, be bad for you.

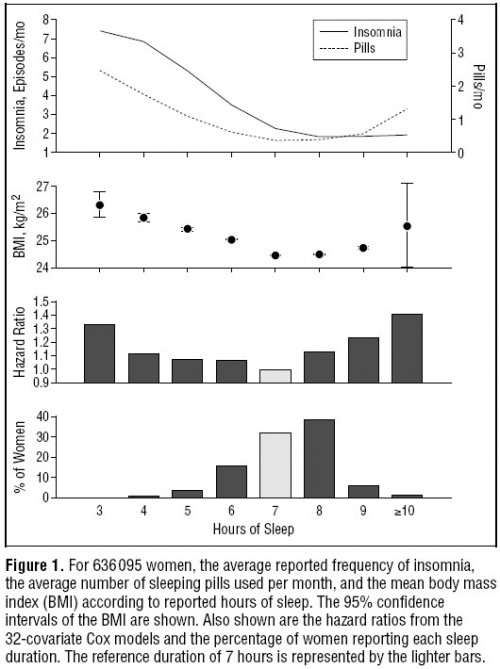

That conclusion is also suggested in the following chart from “Mortality associated with sleep duration and insomnia,” by Daniel Kripke, Lawrence Garfinkel, Deborah Wingard, Melville Klauber, and Matthew Marler. In the figure, the “hazard ratio” is for mortality. Also, this figure is for women, but one for men telling the same basic story is also provided in the paper. Notice that sleeping 8, 9, or 10 hours is actually worse than sleeping 6, 5, or 4, respectively. In fact, 8 hours is worse than 4. Seven hours of sleep appears optimal, and insomnia isn’t so bad! And, yes, the researchers controlled for some stuff (see footnote**).

Even with all their controls, though, can we be sure it’s sleep duration that drives the mortality results? No, of course not. I know from personal experience, it doesn’t take much to disrupt sleep. For example, a bad back or depression can shorten sleep duration. They’re not among the controls in the study. There are many medications that lengthen it, not all of which were controlled for, among other things. Sleep researchers know this.

Much of the data indicates that some but not all of the excess mortality among the long and short sleepers is due to differences in the characteristics of the individuals who comprise these groups; for example, individuals who report shorter and longer sleep times are more likely to be in poorer overall health and to have been diagnosed with medical conditions, including depression, than individuals who report average sleep times (Ayas et al., 2003a; Ferrie et al., 2007; Kohatsu et al., 2006; Patel et al., 2006). Further, lower income has been shown to be associated with both shorter and longer sleep (Ferrie et al., 2007; Patel et al., 2006); therefore, it has been hypothesized that the association between short sleep and mortality may be due to socio-economic status.

The socio-economic hypothesis is fascinating. Of course there is also a connection between it and mortality, so it’s the perfect culprit, possibly explaining why sleeping more or less than about 7 hours is associated with higher mortality. Still, it’s only a hypothesis. And, I don’t really understand what mechanism would relate socio-economic status to shorter and longer duration sleep.

Be that as it may, I remain a bit skeptical that we really know that long and/or short sleep itself increases mortality risk. In this, I have a lot of company. In a very good review article on mortality and sleep duration, Michael Grander, Lauren Hale, Melisa Moor, and Nirav Patel write

Both under adjustment and over adjustment present concerns. Not adjusting for enough variables could mean that some relationships are driven by third factors, and not by sleep duration. Over adjusting may remove some of the causal effects of sleep, if the covariate is on the causal pathway between sleep and mortality.

By the way, in a companion review some of the same authors write,

Over 40 years of epidemiological studies have examined the association between habitual sleep duration and risk of mortality. These studies, spanning several decades and continents, and including millions of study participants, have replicated the pattern that ‘‘short sleep’’ and ‘‘long sleep’’ (with varied definitions across studies) are associated with increased mortality relative to those in the normative group–usually this consists of those sleeping 7–8h. In addition, studies comparing several sleep duration groups have generally found that the further the deviation from the normative range, the greater the increase in mortality risk.

But notice the continual use of “associated” and nary a use of “cause.” All we can say is that sleeping about 7 to 8 hours is what healthy people tend to do. There’s no evidence sleeping longer is helpful, and it could be harmful.

* Not all studies used exactly the same comparison group, but the vast majority used 7-8 hours.

** Here are their control variables: age, race, education, occupation, marital status, exercise level, smoking at intake, years of smoking, churchgoing, fat in diet, fiber in diet, reported sleep duration, insomnia frequency, self reported illness or being “upset,” body mass index, leg pain, history of heart disease, hypertension, cancer, diabetes, stroke, bronchitis, emphysema, or kidney disease, sleeping pills, Valium, Librium, blood pressure medication, diuretics, Tylenol, Tagamet.