Some people argue that mass shootings in America result from mental health problem and require mental health policy solutions. Can this work?

Let’s think through the possible mental health policies for preventing mass shootings. I see three: 1) we could reduce the social determinants of mental illness to lower the population prevalence of mental disorders, 2) we could increase the availability of treatments for mental illnesses, and 3) we could attempt to identify the specific individuals likely to kill and get them into treatment.

1. Reduce the population prevalence of mental illness. Mental illness is associated with social adversity. The causality runs both ways: getting ill will hammer your life and, conversely, falling down the social gradient substantially increases your risk of getting ill. Providing more and better jobs and improving the social safety net would raise the well-being of Americans and, plausibly, reduce the population prevalence of mental and substance abuse disorders.

However, the causal association between mental illness and mass killing is weak. Few mentally ill people ever kill anyone. A mentally ill person is, at worst, only slightly more likely to be violent than anyone else. Conversely, it is not clear how many mass shooters were mentally ill. So even a substantial reduction in the prevalence of mental illness would have only a small effect on the number of mass shootings.

2. Increase the availability of mental health treatments. Let’s stipulate that if you are mentally ill and you are at risk of carrying out a massacre, mental health treatment might help you avoid this tragedy. Access to mental health treatment could be increased by training more evidence-based mental health providers, insuring the uninsured, and requiring that health insurance cover mental health treatment.

Unfortunately, the effect of increased access on mass shootings would be limited, because a) it’s likely that many potential shooters are not mentally ill; b) even with improved access, not all mentally-ill potential killers will seek treatment; and c) mental health treatment doesn’t always work.

Policies 1 and 2 are eminently worth pursuing because they would reduce mental illnesses and the suffering they entail. However, they would be expensive, and few of the politicians who talk about mental health as a response to mass killing support these policies. In any event, these strategies would have at best small effects on mass murders.

3. Identify likely mass shooters and deliver mental health care to them. This policy is a non-starter because of the mathematics of prediction. Murderers are too rare in the population. Any conceivable prediction model will generate overwhelming numbers of false positives. There is no Minority Report future world.

In summary: America needs better mental health care. However, the nation is unlikely to make the required effort, and if it did, it wouldn’t have much effect on mass shootings.

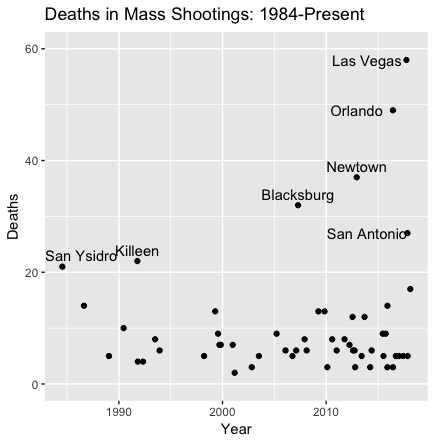

I have updated my graphs of mass shootings to include yesterday’s killings in Parkland, FL, but nothing in the overall pattern has changed. This graph plots the number of deaths in shootings that killed more than four people.

This plot only labels shootings that killed 20 or more, so Parkland with only 17 doesn’t get a label. It is, oxymoronically, a routine massacre. As someone noted on Twitter yesterday, it’s a bitter irony that the 1929 Valentine’s Day Massacre involved only seven murders.

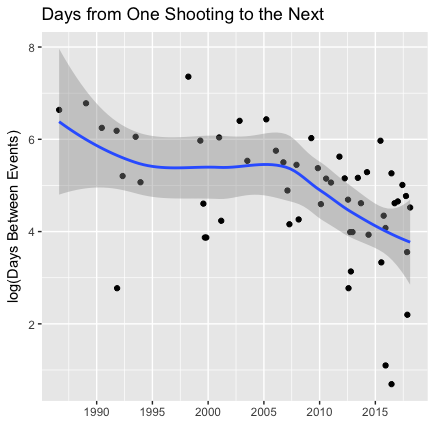

The next graph plots the logarithm of the number of days between successive mass shootings against time and adds a smoothed curve. The declining curve starting in about 2007 indicates that mass shootings are happening increasingly frequently.