The following is a guest post by Allan Joseph, a medical student at the Warren Alpert School of Medicine at Brown University. You can follow Allan on Twitter: @allanmjoseph. (Note from Austin: I recently read TAHCP and found it to be thought provoking and an excellent source for the history of American health and social services. The case studies quoted provide valuable insight one doesn’t get from quantitative analysis alone.)

Annie Lowrey had a fantastic piece in the New York Times this past Sunday exploring the relationship between geography and health outcomes, using Virginia’s Fairfax County and West Virginia’s McDowell County as case studies.

Fairfax County, Lowrey explains, is one of the richest counties in America, and in turn has one of the highest life expectancies in the country: 82 for men and 85 for women. McDowell County, on the other hand, is one of the poorest in the country, with predictably short life expectancy: 64 for men and 73 for women—about the same as in Iraq.

It’s excellent reporting, especially with its grasp of the underlying research, so go read it in full. One thing Lowrey didn’t mention, however, was the link between the social determinants of health (which often correlate with geography) and healthcare costs. That’s where The American Health Care Paradox, a new book by Elizabeth H. Bradley and Lauren A. Taylor, comes in.

TAHCP aims to shed light on the titular paradox, familiar to readers of this blog—why does America get such poor health outcomes, given the staggering amount spent on healthcare? It turns out that Bradley and Taylor don’t think America’s spending too much on improving health—it’s that it’s spending on the wrong things.

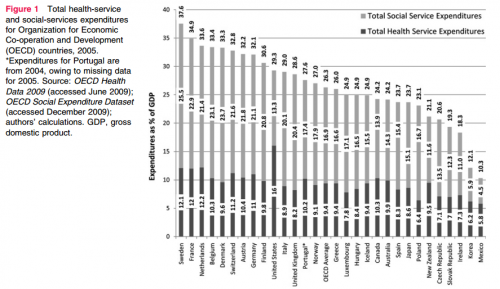

Before we dive into the book itself, let’s go back to the original research that sparked TAHCP, published back in 2011. Bradley and her coauthors took two decades of commonly-used OECD data on healthcare spending, social-services spending, and health outcomes, and tried to make sense of it all.

The key finding is buried a bit in the figure below (click to enlarge):

Look closely and you’ll see that the United States is not exceptional in terms of its total spending on health and social services. But it is exceptional in how little it spends on social services relative to health. It spends $0.91 on social services for every dollar it spends on health services, compared to the OECD average of $2 on social services relative to a dollar on health.

The book examines the American experience with more recent data. Most importantly, the authors find this:

[I]n 2007, while the United States ranked highest in health spending, it ranked only thirteenth in spending on health services and social services combined (p. 17).

In terms of total spending that affects health, America’s actually right in the middle of the pack—implying a gross misallocation of spending: too much spending in health services, and too little in social services. This is the core assertion of the book: implicating the social determinants of health as a central player in the problems of American healthcare.

Bradley and Taylor leverage this finding to create a quality book. They outline the historical development of the social-service and health-service sector, show that they split early in American history, unlike in other countries, which see them as two facets of the same system. That’s helpful information to have, if only to understand that the gulf between the two worlds is wide, and it’s not a simple task to shift spending from health services to social services.

Perhaps most importantly for lay readers, the book brings the data to life. It demonstrates, with case studies, how social services—or the lack of them—can directly impact health. The stories will be familiar to anyone who has worked in health care, and they’re not limited to the poor. Take, for example, the story of Barry, a business executive whose startups went under:

As this business closed its doors in the same year it opened, Barry found himself financially and emotionally depleted. He was without a permanent home, unable to pay rent, and feeling like a failure…Barry is now morbidly obese, at six feet tall and 320 pounds, a binge eater, and prediabetic. He is uninsured and lives in temporary housing. He suffers from frequent leg cramps, periodic chest pain and despondency, and is in the early stages of developing some of the costliest disease to treat, including clinical depression, heart disease, and diabetes. (p. 53)

The stories of patients—and of change in America and abroad—help bring potential policy solutions into focus, too. Often, wonks forget to tell stories, and storytellers forget the data. TAHCP strikes an excellent balance between the two.

The weakness of the book is that it’s based on associations and correlations, not on strict causative research. That’s not a fatal flaw. Beyond the sheer difficulty of proving causality in such a messy subject like this one, there are very good putative mechanisms for causation to run from “low social spending” to “poor health outcomes,” many of which are evident in Lowrey’s piece. Importantly, Bradley and Taylor aren’t saying that the lack of social spending is the only problem in American health care, but rather that it’s an important one that’s too often ignored in healthcare debates.

So what does all that have to do with Fairfax and McDowell counties? Well, Lowrey mentions that Fairfax County offers its residents exceptional social services, including public schools (which are an important force for health). It also has relatively lower Medicare spending. Nationally in 2009, per capita price-adjusted Medicare reimbursements were $9,477. McDowell County clocked in above-average: $9,534—but Fairfax County, with more generous social services had nearly 20% lower per capita health care costs: $7,861. (Data from the Dartmouth Atlas.) There are confounding factors, of course, but Bradley and Taylor would be the first to tell you that Fairfax County’s robust social services likely play a big role in keeping that spending down.

TAHCP doesn’t solve the paradox it illuminates, nor does it purport to. But for anyone interested in health policy, especially those who rarely think about the social determinants of health, it’s an important step down the road towards addressing it by reframing the issue with a wider lens. And without a doubt, TAHCP provides insight to help understand the stories of Fairfax and McDowell Counties and their residents—stories repeated around the country.