Adrianna, Nicholas, Aaron, and Austin and Aaron have written thoughtful pieces about what the Republicans will do about the ACA. The Republicans have power and hold the initiative. Even so, progressives have choices about how to respond, conditional on what the Republicans do. Austin discussed the Democrats’ choices here. Let’s take that discussion a step further.

The Republicans can repeal and, if they choose, replace the ACA. They can do it either through budget reconciliation bills or through an ordinary resolution.

If the Republicans proceed only through reconciliation, they do not need Democratic votes. The Democrats will hate an ACA replacement passed this way. They would hate it because of the procedure. But they’d also hate the bill itself. It’s a selection effect. If Republicans had a bill that Democrats liked, they would pass it through an ordinary resolution. In the short run, if the Republicans replace the ACA through reconciliation, progressive options are protesting and then watching in horror.

But at some point, a left/centre coalition will regain control of the US government. When it does, health care progressives will need a new design for health care reform. By this point the ACA will be, as Trotsky said, in the dustbin of history. So while the left is out of power, progressives need to clarify what they want. Republicans did not do this and are paying for it in confusion about what the ACA replacement will contain.

So what happens if the Republicans try to pass an ACA replacement through an ordinary resolution? An ordinary resolution will need 60 votes to overcome Democratic filibusters.* Getting to 60 requires the Republicans to find Democratic votes. Friend-of-the-blog Dan Diamond interviews conservatives Douglas Holtz-Eakin and Avik Roy here, and they argue for using an ordinary resolution. They believe that bipartisan health care reform will be more likely to survive a Democratic resurgence than a purely Republican bill.

If the Republicans offer the Democrats a deal, should they take it? I expect that there will be two points of view. Call them the compromise and the intransigent views.

The compromise view is this: take the deal if it gives more people health insurance than a reconciliation bill would. As Austin put it, the Republicans have

a gun to the Senate Democrats’ heads, so to speak. “Do you want something or nothing?”

This is the moral argument for compromise. The well-being of the uninsured was the main point of the ACA. Refusing the deal will deprive tens of millions of people of insurance. Getting something for a subgroup beats getting nothing for anybody.

Intransigent progressives would refuse the deal. By their lights, it would be politically and morally disastrous.

The political problem begins with the Republicans’ replacement ACA. It will likely deliver fewer benefits to less affluent Americans than the ACA did. This is not what Avik and other reform conservatives intend. Unfortunately for them, universal access implies a significant downward redistribution of resources. This spending will compete against top-bracket tax cuts, weapons, and building a wall. Given these choices, Republican legislators won’t pick redistribution.

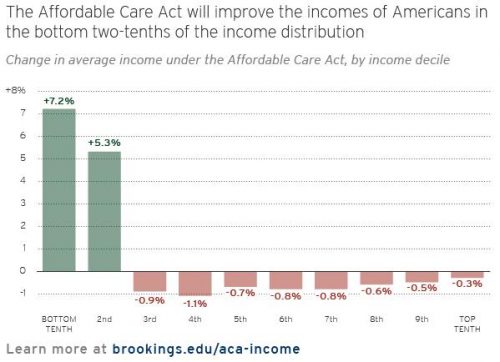

So the replacement offered in the deal will redistribute less than the ACA did. This is a political disaster. The 2016 election showed how little support the ACA generated among many less affluent Americans. One reason why is that it only benefited the least affluent. You can see it in this graph from Henry Aaron (discussed here).

The bottom 20% gained a lot from the ACA. But the maybe-not-poor-but-still-highly-stressed people in the 3rd, 4th, and 5th deciles lost money. Are we surprised that any of them hated the ACA? Or that some of them voted Republican in 2016? Well, they’re going to hate the Republican replacement as much or more.

Canny Republicans know this, and this is why they will want a bipartisan bill. As Paul Waldman explained:

given that Republicans don’t actually need [the Democrats] to pass anything.., all [the Democrats’] support does is put a bipartisan veneer on what Republicans were going to do anyway.

A bipartisan bill gets the Republicans off the hook for the hardship their replacement will cause.

Worse, if Democrats endorse an ACA replacement, they lose an opportunity for political education. Senator McConnell — who is both lucky and a genius — explained this well:

“It was absolutely critical that [every Republican] be together [in opposition to the ACA] because if the proponents of the bill were able to say it was bipartisan, it tended to convey to the public that this is O.K., they must have figured it out.”

Resolute opposition to the ACA taught the GOP base that the ACA was, by Republican lights, a terrible bill. McConnell was right. The way to build political support for true universal access is to refuse to compromise.

Finally, what about the compromisers’ moral argument that health insurance for some is better than nothing? Well, you compromisers don’t actually know how that calculus will work. Under your compromise, tens of millions will be without health insurance for decades. By fighting, we may achieve universal access sooner than that. So it’s not clear that your compromise is superior on utilitarian grounds. Moreover, by our lights, access to health care is a right, not just another benefit. We don’t compromise on rights.

Of course, the compromiser has rejoinders to the intransigent. I’m not endorsing either view. My point is this. Progressives need to think tactically about the possible Republican repeal and replace initiatives. But we also need to think strategically. Senator McConnell took the long view, and look where it got him. The defeat of the ACA reset the game. We can and must think deeply about what we want in health care reform.

* Or the Republicans could end the filibuster. Then they could pass an ACA replacement through an ordinary resolution without Democratic votes. Or as Austin points out here, the Republicans could try to use the filibuster to trap the Democrats.

I think Democrats would filibuster [any Republican ACA replacement] they could. The filibuster is not set in stone. A Senate majority can change it,… But that doesn’t appear to be what the Senate will do — they’ll retain the filibuster. This could play to their favor, since they can propose things they like, let the Democrats filibuster them and take the blame when repeal kicks in with no replacement. Perhaps that’s another way for Republicans to get out of their political bind.