The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2015, The New York Times Company).

Can hospitals provide better care for less money? The assumption that they can is baked into the Affordable Care Act.

Historically, hospital productivity has grown much more slowly than the overall economy, if at all. That’s true of health care in general. Productivity — in this case the provision of care per dollar and the improvements in health to which it leads — has never grown as quickly as would be required for hospitals to keep pace with scheduled cuts to reimbursements fromMedicare.

But to finance coverage expansion, the Affordable Care Act made a big bet that hospitals could provide better care for less money from Medicare. Hospitals that cannot become more productive quickly enough will be forced to cut back. If the past is any guide, they may do so in ways that harm patients.

The Obamacare gamble that hospitals can become much more productive conflicts with a famous theory of why health care costs rise. William Baumol, a New York University economist, called it the “cost disease.” (He wrote a book about it by that title; I blogged on it as I read it if you’d like to quickly get the gist.)

This theory asserts that productivity growth in health care is inherently low for the same reason it is in education: Productivity-enhancing technologies cannot easily replace human doctors or teachers. In contrast with, say, manufacturing — a sector in which machines have rapidly taken over functions that workers used to do, and have done them better and more cheaply — there are, at least for the time being, far fewer machines that can step in and outperform doctors, nurses or other health sector jobs.

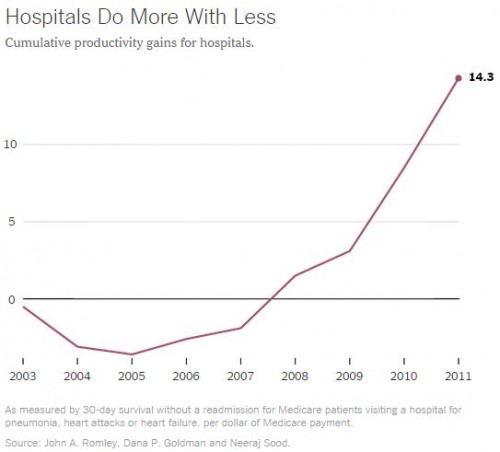

But a new study casts doubt on that theory and suggests Obamacare’s bet may indeed pay off. The study, published in Health Affairs by John Romley, Dana Goldman and Neeraj Sood, found that hospitals’ productivity has grown more rapidly in recent years than in prior ones. Hospitals are providing better care at a faster rate than growth in the payments they receive from Medicare, according to the study.

[Note: y-axis is cumulative percent increase in productivity, as defined in the chart’s footnote.]

This is both good news for patients and good news for the financing of the health reform law, which assumes hospitals will become significantly more productive. This bet is built into a schedule of reductions in the rate of growth in Medicare payments to hospitals. According to the law, those rates are to be reduced commensurate with the productivity growth of the overall economy. The only way for hospitals to keep up is if their productivity rises just as quickly.

The cost disease theory says it can’t be done. This, according to the theory, is what causes health care spending growth to outpace that of the overall economy.

Computers, cellphones, televisions — over the years they’ve all gotten better and cheaper. High productivity growth in such sectors — not mirrored in health care — leads to wage growth in those sectors. Higher wages provide more resources to spend on goods and services. Because health care is valuable, we use those resources to pay health care workers more, too, to keep them from doing something else. This helps explain why health care spending outpaces economic growth: We keep paying more for health care (through growing wages) without getting more (because of low productivity growth).

Not all economists find every detail of the cost disease theory compelling. Some have argued, for example, that it gives short shrift to ways in which the quality of care changes, along with its price. Heart attack treatment certainly costs more today than a decade ago. Perhaps it’s also better. The acceptance of inevitably low health care productivity growth also troubles some economists.

Amitabh Chandra, a Harvard economist, is one of them: “In Baumol’s view, as long as there is a steady stream of innovation in sectors others than health care — from cars to computers to everything on Amazon — we’ll be able to spend even more on health care, despite its jaundiced productivity growth. But if productivity in health care improves, too, then think about how much more health care we’ll be able to afford.”

If the cost disease theory’s premise of low health care productivity growth holds, then the idea of tying reductions in the growth of Medicare payments to hospitals to economic growth — as the Affordable Care Act does — spells trouble.

The findings by Mr. Romley and colleagues from the Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics at the University of Southern California are a hopeful sign this need not happen. A strength of the study is it incorporated an aspect of the quality of care into its measure of productivity: whether the care received kept more patients alive and out of the hospital for at least 30 days. The findings were qualitatively similar for shorter (two weeks) or longer windows (one year). This distinguishes it from other approaches that measure productivity according to how many procedures a hospital can do per dollar, but not how well they do them.

According to the analysis, productivity fell for heart attack and heart failure patients between 2002 and 2005, after which it began to rise. For hospital care for all three conditions examined — heart attacks, heart failure and pneumonia — productivity growth accelerated after 2007. By 2011 it was more than 14 percent over the level it had been in 2002.

The source of the broadest optimism from the study: Hospital productivity increased in the most recent years faster than that of the overall economy.

Though the study is an important one, we should interpret it with some caution. It examined only one measure of productivity; it examined only three conditions in Medicare patients; and it examined data only through 2011. More studies like this one — but using different methods and more recent data — could confirm or refute these findings.

Nevertheless, for decades the conventional wisdom has been that hospitals — and the health care sector in general — could not become more productive, explaining its growing expense. This new study suggests that such a cost disease may not be as inherent as once believed — and that the health care law’s cuts to Medicare are not as risky a bet as they once seemed.