The following is a guest post by Allan Joseph, a medical student at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University and TIE research assistant. You can follow Allan on Twitter: @allanmjoseph or email him. This post is part of a series on the Institute of Medicine’s report on graduate medical education (GME), which you can follow with the tag IOM on GME.

Perhaps one of the most common arguments for federal GME funding is that without it, the academic medical centers (AMCs) that are the linchpins of medical training would be far worse off. The argument suggests that certain services provided by AMCs are unprofitable to AMCs but valuable from a social perspective — and thus ought to be subsidized. Since money is fungible and those activities aren’t subsidized elsewhere, GME funding might be thought of as a subsidy for these other activities. If you’re skeptical that GME funding is needed to increase GME training slots (and I am), it’s still worth considering this argument for the subsidy.*

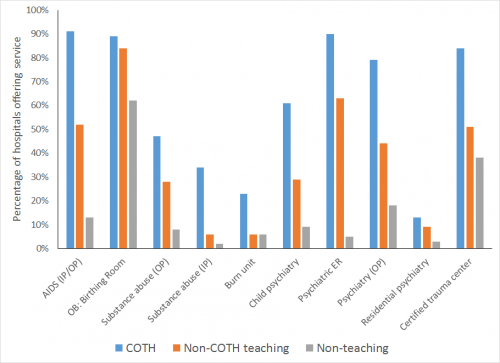

So what are “unprofitable” services? Opinions vary, but this Health Affairs paper lists them as treatment for AIDS, substance abuse, burns, and trauma, as well as inpatient and emergency psychiatric units, emergency rooms, child psychiatry, and obstetrics among them.

If GME funding is serving to subsidize these services, then we’d expect teaching hospitals that receive GME funding to be more likely to offer them. Thanks to a helpful analysis of American Hospital Association data provided to me by Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) staff, we can examine this question for fiscal year 2012. The chart below shows the percentage of large teaching hospitals, small teaching hospitals, and non-teaching hospitals that offer a particular service.

(For reference, “IP” = inpatient, “OP” = outpatient, “OB” = obstetrics, and “COTH” is the AAMC’s Council of Teaching Hospitals, the group representing the roughly 400 largest teaching hospitals.)

From the graph, it’s clear that teaching hospitals are far more likely to offer these services than non-teaching hospitals, and larger teaching hospitals are even more likely. That’s a strong sign that GME funding might in fact be helping hospitals offer these services.

The problem is that this is pretty rough evidence. We’re counting services that we think are unprofitable, not ones that we know are unprofitable.

There also might be other ways to explain this data:

- Teaching hospitals are more likely to be government or nonprofit hospitals, and these services are generally more likely to be offered by these types of hospitals.

- The same data analysis shows that COTH hospitals are only about 5% of hospitals yet account for 22% of admissions and 19% of hospital beds. This means that they’re much larger hospitals, on average, and therefore might have economies of scale, pricing power, or other advantages that allow them to extract greater profits in profitable services and cross-subsidize unprofitable services.

- Teaching hospitals may also receive Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments as safety-net hospitals that they can use to subsidize unprofitable services.

- Teaching hospitals might be supported by externally-funded research in areas considered unprofitable. Even if that support doesn’t fully offset costs, such hospitals might be willing to accept losses in order to accommodate prestigious research programs. (It’s not hard to imagine that infectious-disease physicians working on AIDS research might want to join institutions that actually treat AIDS patients, for example.)

From the graph, this does seem to be the strongest argument for GME funding: cuts in GME funding might mean that AMCs stop offering unprofitable services like those above. But we really don’t know for sure; it’s almost impossible to draw further conclusions without better research to rule out other explanations such as those above.

The IOM committee struggled to provide good information without answers to many questions, and we too should probably refrain from making stronger conclusions until we get more research. A great place to start for any enterprising researcher would be examining the proportion of hospitals offering each service in the chart above over time in the same way that the proportion of GME slots over time has been examined. Cuts and changes in funding could provide us information on the role GME funding plays in subsidizing these services as well.

The debate will continue for the foreseeable future, but hopefully the IOM report will at least have shifted it towards using more evidence. It’ll be imperfect evidence — such are the travails of policy research — but if considered thoughtfully, imperfect evidence is better than no evidence. After all, when we’re talking about $15 billion of yearly funding, the least we can do is be thoughtful.

*This argument isn’t to say that calling it “GME funding” instead of “AMC funding” is a total misnomer. These unprofitable services are often required to offer residency training: for example, you can’t offer a psychiatric residency without inpatient psychiatric services. So in some way this is related to medical training, but that’s a side issue.