The following is the text of my email to Peter Friedmann, Brown University Professor of Medicine and Professor of Health Services, Policy & Practice and an expert on substance use and addiction medicine:

In response to my NYT piece on treatment for opioid dependence, I received email with a question I thought I answered in the post: why should we replace one addiction for another?

But now I suspect there’s something else behind this question that I did not address because I didn’t know how. Perhaps people think that longer-term opioid dependents are getting high rather than relieving cravings when they use. And, maybe some also think that by prescribing methadone or buprenorphine, one is just offering a legal way of obtaining that high.

I can imagine that if one thinks that opioid users are getting high both ways, then using substitution therapy feels somehow like an illegitimate way to treat the chronic condition: replacing one addiction for another, as they say. Is there any truth to this?

Peter’s response:

The concern you describe speaks to a common misunderstanding of the definition of addiction.

Substance addiction is a behavioral disorder characterized by a compulsive drive for the reinforcing euphoria, loss of control over it, and substance use despite adverse consequences leading to the sacrifice of normative life goals, values, coping mechanisms and functioning (including health, family, work, etc.) at the altar of the substance.

People often confuse physical dependence (tolerance and withdrawal) with addiction (partly because the confusing DSM-IV and earlier definition of substance dependence was synonymous with addiction). The oral, long-acting opioid agonists currently FDA approved to treat opioid use disorders produce physical dependence, but by diminishing the reinforcing effects of short-acting opioids they function to extinguish addictive behavior.

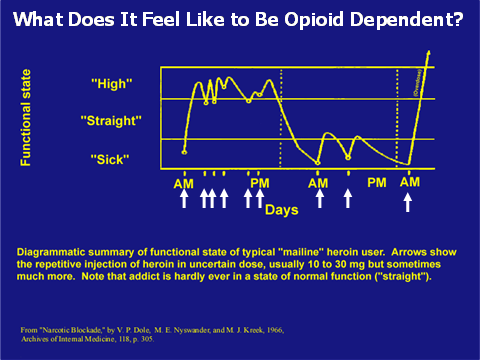

The chart above gives you an idea of the difference – drug users of short-acting opioids like heroin or oxycodone spend most of their days either “high” or “sick” – and require multiple doses a day. Over time the development of tolerance often means they are either sick or straight – they no longer get high (more complex discussion – but at this point they need a higher dose, more potent opioid or to change to a more direct route of administration to get high again – but eventually tolerance will occur again).

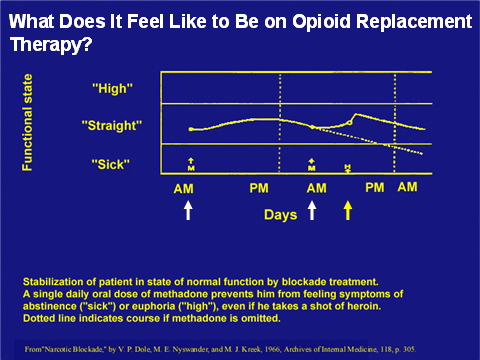

The goal of maintenance doses of long-acting opioids like methadone or buprenorphine is to keep them straight (feeling normal) for most of the time, as opposed to feeling either “high” or “sick” most of the time (see chart below)

The idea is that blocking the euphoria (positive reinforcement) and stopping the withdrawal symptoms (negative reinforcer for cessation) will extinguish the antisocial and dysfunctional behaviors. Spending more time feeling normal also allows the patient to focus on the difficult process of self-exploration, life re-orientation and relationship re-building necessary for long-term remission and recovery.

Now I know, and you do too. See also Peter’s interview with Harold Pollack.