The following is a guest post by Galen Benshoof, a Master in Public Affairs candidate at Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School, where he focuses on health policy. Find him on Twitter: @benshoof.

Critics of the Affordable Care Act have a new bugbear: a program known as risk corridors, which is part of a trio of premium stabilization mechanisms collectively known as the 3Rs.

Back in November, Senator Marco Rubio introduced legislation aimed at doing away with risk corridors, branding the program a “bailout” of insurance companies. Over the past few weeks, multiple conservative media outlets have joined in the call for repeal.

Recent reporting on risk corridors has left plenty of questions unanswered. Here, I hope to provide a simple explanation of what the risk corridor program is and what it isn’t.

What it is

1. It’s certainty for insurers. Think of risk corridors as a hedge for insurers. Back in early 2013, they were facing a brand new market, with a huge amount of prospective consumers but little information on who among them would actually enroll. Thanks to the introduction of guaranteed issue and the departure of risk rating, they knew of the potential for adverse selection in the new market. For the first time, many sick people would now have access to insurance. Those consumers would seem likely to enroll, because they urgently need coverage and care. Less clear is the behavior of healthy people, who tend to pay more in premiums than they cost in claims. So if you’re an insurer facing this uncertainty, what do you do?

Maybe you don’t offer plans on the exchange at all. Or, if you’re set on participating, a conservative approach would be to set premiums high, so that you are less likely to pay out more in claims than you take in through premiums. But the higher you price your products, the fewer healthy people are interested in purchasing them. And the fewer healthy people you have, the greater your proportion of sick people, meaning you may have to raise premiums yet again. That is a pattern that the architects of the ACA were interested in avoiding.

Enter risk corridors. The program is a way for the federal government to give a little security to (and get some from) insurers in the new market by sharing in the losses (and gains) of all exchange carriers. Thanks to risk corridors, insurers know that any losses they experience will be limited, motivating them to enter the market in the first place and then to price rates competitively, which triggers competition among plans and choice among consumers.

2. It’s an affordability mechanism. Because risk corridors attenuate losses, insurers are better able to price their premiums competitively. That means lower premiums for consumers. Thus, the largest beneficiaries of risk corridors are consumers themselves! And some seek to take away that benefit. Depending on how enrollment looks in a couple of months, repeal of the risk corridor program could easily mean higher rates for consumers: insurers would no longer have a vital shock absorber, so they might feel compelled to raise their rates for 2015.

3. It’s only temporary. Risk corridors were intended to offer certainty during an uncertain period. They begin in 2014 and end with the third year of the ACA’s exchanges, in 2016. Once insurers have some experience with the new market, and once claims come in over the course of this year and next, they’ll have a better sense of what kind of risk pool they are facing and what their premium prices should be. Risk corridors help them get safely to that point, benefitting consumers in the process.

What it isn’t

1. It isn’t a bailout. Many talented writers have already covered this territory. For agreement that risk corridors do not constitute a bailout, I’ll point you to conservatives Yevgeniy Feyman and Scott Gottlieb and progressives Jonathan Cohn and Sy Mukherjee.

I’ll add one thing to their arguments: risk corridors are different from Wall Street bailouts because the moral hazard created by risk corridors ends up benefitting consumers. Risk-taking under risk corridors means low premiums for consumers and potentially some payment from the federal government. Risk-taking on Wall Street resulted in massive losses for investors and payouts from taxpayers. Put a different way, the most potent criticism of Wall Street bailouts was that they privatized gains and socialized losses. But the gains under risk corridors accrue broadly, to millions of consumers in every state across the country.

2. It isn’t new. As Cohn notes, risk corridors are not a feature unique to the ACA. In fact the program appears in Medicare Part D, legislation passed under President George W. Bush and a Republican-controlled Congress. Furthermore, while risk corridors in the ACA are only a temporary measure, the version in Medicare Part D is permanent.

3. It doesn’t guarantee federal spending. Yesterday, the WSJ posted a risk corridor explainer. Drawing a contrast with risk corridors, they write that risk adjustment, another one of the 3Rs, “is less controversial because it doesn’t call for any federal spending”—the implication being, of course, that the risk corridor program calls for federal spending. However, that’s a bit misleading. Although the reporters’ language implies that federal spending is a foregone conclusion, in reality it’s conceivable that net federal government outlays on risk corridors is zero. That’s largely because of two program characteristics:

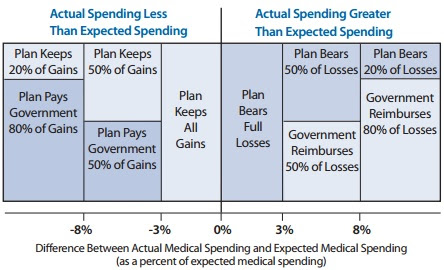

First, some insurers will not pay or receive anything at all. Quoting KFF’s excellent recent explainer: “If an insurer’s actual claims fall within plus or minus three percent of the target amount, it makes no payments into the risk corridor program and receives no payments from it.” Thus, insurers who priced their premiums close to the cost of their claims do nothing with regard to risk corridors, meaning no cost (or benefit) to the federal government.

Second, for the insurers above or below the three percent marker, some may receive payments and some may make payments. Plans with greater than expected gains make payments to the federal government, and plans with greater than expected losses receive federal payments. (See the chart below, from an American Academy of Actuaries fact sheet on ACA risk sharing provisions.) There could easily be plenty of instances of both. It’s possible, in other words, that the two sides actually cancel each other out. It’s even possible that the program ends up being a net money-maker for the federal government.

But the final result is up in the air. On one hand, last November’s like-it/keep-it fix could cause an increase in risk corridor spending in a handful of states (see Nicholas Bagley for more on that). On the other hand, the final risk pools may be healthier than expected: apparently most current enrollees were previously insured, meaning they were able to get insurance before the ACA, often impossible for sicker populations. But then again demographics could change between now and March: we could see increased enrollment among previously uninsured enrollees, who are likely to be higher-cost.

It’s hard to predict what will happen with the program, in the end. But it’s important to recognize that while federal spending on risk corridors is possible, it certainly isn’t assured.

A slightly different version of this post originally appeared at Project Millennial.