The most recent edition of Health Affairs contains a provocative paper by Thomas Bodenheimer and Mark Smith; it opens by imploring we halt our reliance on “policy wish lists” when it comes to the primary care shortage facing the United States. Increasing capacity through new physicians would take decades, they argue. Improving reimbursements isn’t feasible; we’d need to hike Medicare rates for primary docs by 50% to narrow the gap with specialty care.

The authors propose that “shortage” is a misnomer and we need to reframe the problem to tackle it productively:

The first step is to redefine the crisis, which is currently mislabeled as a physician workforce shortage. The accurate formulation is a demand-capacity mismatch. Primary care practices could greatly increase their capacity to meet patient demand if they reallocate clinical responsibilities—with the help of current technologies—to nonphysician team members and to patients themselves. Physicians often complain that they are responsible for tasks that team members with far less training could perform.

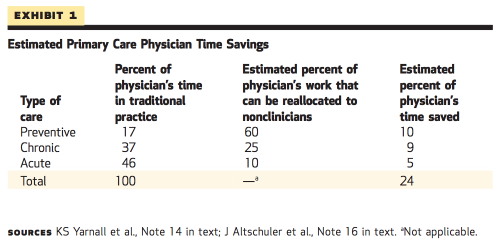

Their analysis finds that nearly a quarter of the average family physician’s time could be reallocated to other members of a primary care team, allowing PCPs to see more patients without extending their hours.

Adding up the potential rechanneling of care from clinicians to nonclinician personnel for preventive, chronic, and acute issues, it is possible that 24 percent (10 percent plus 9 percent plus 5 percent) of clinician time could be saved by sharing the care among a primary care team. The registered nurse and pharmacist workforces are sufficient to add primary care capacity. Expanding the medical assistant workforce could be accomplished quickly and would both enhance primary care capacity and create jobs. Many of these concepts are being implemented in a variety of primary care practices throughout the United States.

Reorganizing primary care delivery looks promisingly straightforward in the paper; the authors outline specific tasks that could be readily redistributed to registered nurses, pharmacists, or other team members. But these efforts would encounter predictable complications. There are regulatory regimes in many states that prevent the delegation of certain authorities to non-physician practitioners. Less tangible cultural divides are no easier to repair—especially when entrenched payment structures favor the status quo.

“Reconceptualizing” the primary care shortage in practice will take a lot of policy legwork, but it may be the most viable solution to a problem that’s been percolating for years. The paper—well worth reading in full–sets up a valuable framework for moving forward.

Adrianna (@onceuponA)