If you thought I was upset earlier, I was just getting started. The nonsense in some medical societies’ clinical guidelines really makes my blood boil.

Let’s go back to the beginning. In 1990, the Institute of Medicine recommended the development of clinical guidelines to reduce inappropriate variation in practice. This commenced an explosion of guidelines. For example, the National Guideline Clearinghouse now includes 471 guidelines for hypertension and 276 for stroke alone. For maximal variation reduction, the number of guidelines you need is one. Though it’s possible all of the hundreds of clinical guidelines on a subject say the same thing, that’s not the case. How can variation be reduced with so many guidelines?

As if that were not bad enough, the recommendations in many guidelines is based on some pretty flimsy evidence, or none at all.

A recent study of the quality of evidence in cardiology guidelines showed that of more than 7000 recommendations, a median of 11% were based on data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 48% on expert opinion, case studies, or standards of care. In this issue of the Archives, Lee and Vielemeyer report on a similar analysis of guidelines in infectious diseases. Their study shows that of more than 4000 recommendations, 14% were based on data from RCTs and 55% on opinion or case series. Both studies showed that although the number of recommendations increased across time, few of the new recommendations were based on RCT data.

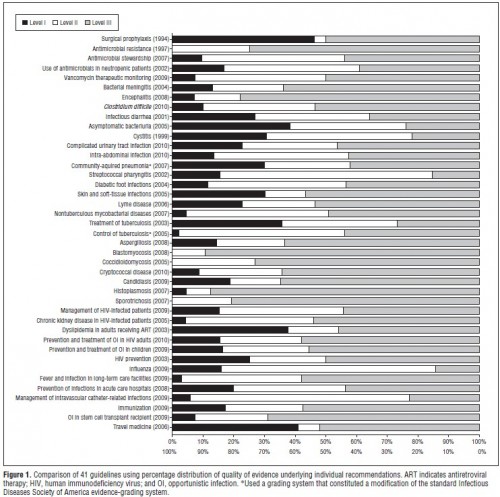

Are you crying yet? If not, maybe a picture would move you. Here’s one from Lee and Vielemeyer (click to enlarge):

In case you don’t know, Level I evidence is RCTs, Level II is from non-randomized trials, cohort or case-controlled studies, and Level III is, you guessed it, from opinions or descriptive studies. The figure above is showing you all the guidelines in the authors’ data that could be analyzed in this way. They didn’t cherry pick. These are all of them. The amount of Level III evidence (grey) should disturb you.

It makes sense to reduce variation in cases for which we have good evidence, such as that from RCTs. It does not make sense to reduce variation in cases for which all we have to go on is expert opinion, case studies, or standards of care. Those are the instances in which we should be encouraging doctors to use their best judgement and encouraging researchers to flesh out the body of evidence. And, by the way, there are also documented cases of guidelines going against what the best evidence says, even RCTs. If you listen to the SMART EM podcasts, you’ll hear about some of them.

Now maybe, in principle, a group of experts can divine an approach that is more likely to do good than harm. After all, following expert opinion is better than nothing, right? No, not always. It depends who the experts are and what their conflicts are. Sadly, we can’t be sure what’s driving the expert opinions that inform many clinical guidelines.

Major guideline-releasing organizations have recognized the importance of having a rigorous policy regarding conflicts of interest; such policies manage and balance potential conflicts rather than eliminating them. The ACC/AHA’s [American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association’s] code regulating potential conflicts of interest requires the collection and publication of relationships with industry by guideline-writing groups as well as peer reviewers. Relationships are orally disclosed at every meeting, votes are recorded for all recommendations, and members with significant conflicts abstain from voting, although they can participate in the discussion. In addition, the ACC/AHA task force now requires that 30 to 50% of writing group members have no conflicts of interest, and the guideline writing group must be chaired by someone with no conflicts of interest. Finally, there is no industry funding for guideline development, although the ACC and AHA do receive industry support for distribution of guideline derivative products such as pocket guides.

I’m sorry, the requirement is that only 30-50% of members of the guideline writing committee have no conflicts of interest?! That’s a joke. That leaves the possibility that a majority of members are conflicted. And industry support for guideline derivatives is not much of a firewall. Worse, the process of some guideline development is opaque. What’s being hidden and why?

All in all, this stinks. In the absence of a transparent, conflict-free process, it’s not unreasonable to throw away recommendations largely based on expert opinion. I think guidelines can play a very helpful role in improving the efficiency of medicine. But they have to be based on something real and they have to be developed in a manner that can be trusted. Is there any sound, patient-centered argument for allowing conflicts and hiding methods?