This is a TIE-U post associated with Jonathan Oberlander’s Political Dynamics and Policy Dilemmas (UNC’s HPM 757, Fall 2011). For other posts in this series, see the course intro.

A year or so ago, the conventional wisdom was that legislative repeal of health reform was a near impossibility. The only hope for opponents of the ACA was via the judiciary, the thinking went. Things have changed since then.

In my mind, the relative odds have flipped. The individual mandate may be litigated before the Supreme Court as early as next spring. In NEJM, Wendy Mariner [1] covered the various angles and issues. However, the chances of a majority opinion against constitutionality seems unlikely. Not impossible, of course, but against the odds.

I draw this conclusion from the sentiments of proponents of repeal, even those involved in bringing the suits. Several of the participating attorneys spoke at an AEI event about the case (part of a good podcast series, by the way). They admitted that they could not easily find five justices that were likely to rule for unconstitutionality of the individual mandate.

However, the individual mandate is not the only point of attack. It’s just the easiest one to pursue while the government is not fully controlled by the Republicans. If the Supreme Court rules that it is, in fact, constitutional, expect opponents of the law to continue in pursuit of repeal, a point made by Jon Oberlander [2]. The chances that pursuit will end successfully for reform opponents will increase if Republicans sweep in 2012. In contrast to conventional wisdom of the past, it now seems plausible that much of health reform could even be repealed with a simple majority in the Senate (via Reconciliation). The filibuster provides protection against non-budgetary items only. So, while judicial repeal seems remote, (partial) legislative repeal may not be.

However, even if the law is not repealed, elements of it are still in potential jeopardy in at least one other way. Parts could be paired back if its budgetary assumptions prove unrealistic. Douglas Holtz-Eakin and Michael Ramlet [3] (ungated pdf here) make the case that they are, in direct opposition to predictions of the CBO (pdf) [4].

Putting most of Holtz-Eakin’s and Ramlet’s analysis aside, I want to focus on one issue, raised with more clarity and precision by the actuaries of CMS (pdf). CMS actuaries note that the law requires Medicare payments to hospitals and physicians to be reduced annually to account for growth in productivity. However, the productivity growth factor is that of “private, non-farm multifactor productivity,” not health care-specific productivity, which has been negative. The long-run private, non-farm productivity growth has been (positive) 1.1% per year. Hence, provider payments will be reduced by that factor, whether health care providers become more efficient or not. Paying less for care that is costing more is not a sustainable strategy.

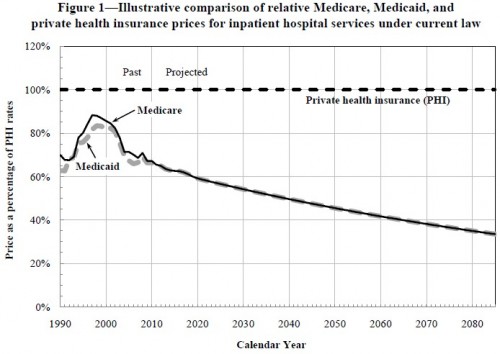

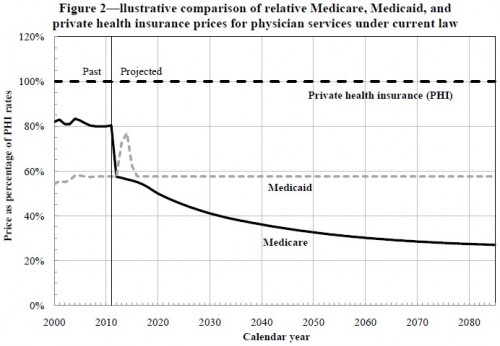

Here’s what this looks like graphically, for hospital and physician services (from the CMS report):

It is not plausible that Medicare rates will fall to roughly 30% of private rates. There is simply no reason to believe that providers would accept such rates. Nor is there reason to believe Congress would sustain them. Instead, several things could happen. One, and most obviously, is that the statutory rate updates will be canceled. In that case, health reform will cost more than predicted, jeopardizing our ability and willingness to fund coverage expansion and benefits generosity in the amount anticipated by the law.

There are other possibilities. The charts above are based on the assumption that there will be no further reform or innovations that change the nature of private health insurance. It could be that private health insurance rates come down along with Medicare’s. To the extent that occurs, Medicare rates will not fall as far below private ones as shown. Note that there is nothing (or little, if you count the Cadillac tax or whatever the IPAB might recommend) in the law to encourage such change on the private side. But the private sector can, in principle, innovate its way toward lower payments on its own. Private market advocates suggest it will or can. Congress could pass reforms to encourage it. In other words, another way to address a widening gap between private and Medicare rates is not to increase Medicare rates, but to push down private ones.

Finally, it is possible that lower Medicare payment growth will, itself, encourage lower private payment growth. This possibility has historical precedent. One, but not the only, reason private payment-to-cost ratios grew in the late 1980s is that Medicare payments were pushed downward, which encouraged hospitals to cut costs. In other words, hospitals can cut costs. In an insurance market capable of taking advantage of that through negotiations–as occurred in the 1990s via managed care–private payments could come down.

It’s far from evident insurers could put adequate pressure on hospitals to reduce payments. Hospitals have considerable and growing market power. But, this is, at least, a theoretical possibility. It won’t be encouraged by weakening insurer market power relative to providers, however. So, it is critical how we continue to reform the insurance market.

My point in all of this is to suggest that there are hidden assumptions in all analysis of health reform budgeting. I do not know which assumptions are likely to be closer to the truth. Time will tell. However, I do know that, one way or another, the payment differentials illustrated in the figures above will not come to fruition. About this, opponents of health reform are correct. Just how reality will deviate from those projections is unclear. It could lead to pairing back of health reform. Or it could usher in more reforms that alter the dynamics of the private market and the wider health care system in ways that improve the chances of reform’s success as envisioned.

References

[1] Wendy Mariner et al. 2011. Can Congress Make You Buy Broccoli? And Why That’s a Hard Question. New England Journal of Medicine: 364: 201-203.

[2] Jonathan Oberlander. 2011. Under Siege—The Individual Mandate for Health Insurance and its Alternatives. New England Journal of Medicine 364: 1085-87.

[3] Douglas Holtz-Eakin and Michael J. Ramlet. 2010. Health Care Reform is Likely to Widen Federal Budget Deficits. Not Reduce Them. Health Affairs 29: 1136-41.

[4] Congressional Budget Office. 2010. Cost Estimate of the Final Health Care Legislation.