I’m blogging my way through The Cost Disease, by William Baumol.  All posts related to the book will be tagged with “Cost Disease.”

All posts related to the book will be tagged with “Cost Disease.”

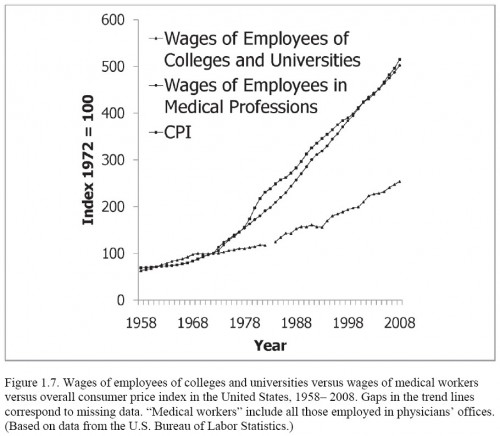

Chapter 1 sets the stage with the central puzzle and a sketch of the solution. The puzzle is observed in health care and higher education. In both, costs* have been rising at rates above that of overall inflation for decades. This is fairly well known and certainly so to readers of this blog. What is probably less well known is that the cost growth above that of inflation is not due to above-inflation wage growth in either sector. The chart below, reproduced with permission from the book’s publisher, Yale University Press, illustrates this fact. I know it’s a bit hard to make out, so I’ll explain it in words.

Inflation, as measured by the consumer price index (CPI), and wages of medical professionals nearly hug each other (the top two lines), with CPI higher from the late 1970s through the late 1990s. The wages of employees of colleges and universities (bottom line) are well below both those of medical professionals and CPI.

So, this is the puzzle, actually two: (1) How can, or why do, costs consistently rise for certain sectors and not others? (2) In the sectors that suffer this “cost disease,” why doesn’t the additional spending accrue to its workers? Baumol, I trust, will answer these questions. In Chapter 1, he provides a sketch:

My argument, in brief, is that the cost disease is largely a product of the unprecedented and spectacular productivity growth that the world’s industrialized nations have achieved since the Industrial Revolution, commonly said to have begun in the eighteenth century, which has contributed so much to standards of living and reduction of poverty. This unprecedented productivity growth—carried out primarily by the partnership of inventors and entrepreneurs and expanded to a large scale by companies, governments, and nonprofits—has all but eliminated famine in wealthy countries, created technology unimaginable in earlier eras, given us ever rising standards of living, and greatly reduced poverty in both extent and severity. But it has also brought the rising costs of health care, education, and other important services. The argument here is that the productivity growth that gives rise to the cost disease also gives society the means to deal with it.

So, I infer (and I also know from prior reading) that the cost disease is due to the difference in productivity growth between the diseased and non-diseased sectors. It’s relatively low in the former and higher in the latter. In reading the book, apart from connecting the dots in the above sketch, I look forward to understanding more about how productivity is measured in health care. To date, I’ve been disappointed with the approaches to this measurement problem I’ve seen. Today’s doctor visit, hospital stay, prescribed drug, and the like are not like those of prior decades. There have been qualitative changes in health care. It is a huge challenge to account for this in measures of productivity. How does Baumol do it, if at all? Let’s find out.

* I’m using “cost” because that’s the term used in the book. We mostly observe spending, which is different.