The following is a guest post by Allan Joseph, a medical student at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University and TIE research assistant. You can follow Allan on Twitter: @allanmjoseph. You can read previous TIE coverage of Sovaldi here.

CVS Health recently released a whitepaper on trends in the use of Sovaldi (sofosbuvir), the hepatitis C drug that’s been making waves for both its effectiveness and costs. Two things jumped out at me from that report that were worth highlighting.

Drug discontinuation

The CVS report used a cohort of about 2,000 patients who recently started hepatitis C treatment that included Sovaldi to assess the rate of discontinuation in these patients — that is, what proportion of patients started Sovaldi and didn’t finish the course for any reason.

About 8% of patients taking a treatment course involving Sovaldi discontinued their treatment, though this varied greatly by the specific regimen (from 4% to 10%). That’s quite a bit higher than in clinical trials (discontinuation rates around 3%), which is causing some alarm. All the evidence suggests benefits of Sovaldi only accrue to those who complete a full course of treatment.

Discontinuation rates are undoubtedly important. A patient who starts Sovaldi but doesn’t finish the course is responsible for costs to the system for no benefit. Yet it shouldn’t be surprising that more patients are discontinuing Sovaldi in the real world than in its clinical trials. Not only do clinical trials depend on providers who are in close contact with their patients, but they enroll the type of patients who are eager to volunteer to try a new drug for their disease, and are thus more invested in the drug they’re taking. I’d be surprised if there were any drugs that had a lower discontinuation rate in the real world than in a clinical trial.

It’s important to put these rates in context by comparing them to previous treatments for hepatitis C. Adherence rates are much more often measured in “real-world” patients than discontinuation rates*, but in at least one clinical trial, discontinuation rates for telaprevir (the standard of care from 2011 to 2013) were about 34%. That’s a lower bound, since as we discussed above, real-world discontinuation rates tend to be higher than those in clinical trials. So even by that standard, patients prescribed Sovaldi tend to stay with it much longer than previous hepatitis C drugs. That’s not to say Sovaldi discontinuation isn’t still a problem, but it’s not as big of a problem as discontinuation of prior hepatitis C treatments, as best we can tell.

Usage trends

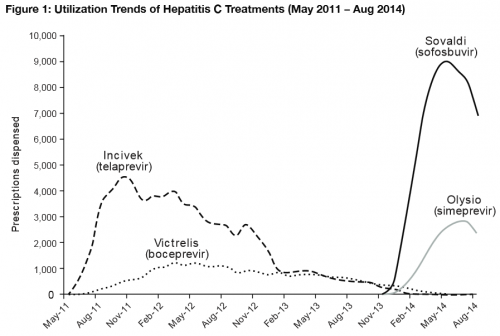

Wonkblog’s Jason Millman highlighted another interesting finding in CVS’ report: After initially skyrocketing, the use of Sovaldi has actually dipped from its peak in the last few months:

As Millman astutely noted, that’s in part because providers are aware that even-newer hepatitis C drugs are scheduled to hit the market very soon, though the one providers are most anxiously awaiting is a combination of Sovaldi with a new drug called ledipasvir that should allow for even easier use by patients. It’s a fascinating trend, though, because it highlights the difficulty of projecting the use of new innovations when you don’t know what the future marketplace for those innovations looks like.

Rationing?

Finally, Eric Schultz alerted me to the preliminary recommendations for Sovaldi treatment issued this week by New York State’s Medicaid program. They’re a very interesting set of guidelines, to say they least. They place the highest priority on treatment for patients with advanced hepatitis C and/or who have other important comorbidities such as liver disease or HIV — yet they place a huge number of restrictions on the prescription of Sovaldi. Because hepatitis C is easily transmitted through IV drug use, patients must show no evidence of alcohol or drug abuse at follow-up appointments to receive the drug, nor should they demonstrate any signs of “high-risk behavior.” Additionally, patients have to undergo routine blood tests during their treatments, while patients with HIV must also demonstrate that their HIV was undetectable before receiving Sovaldi. Finally, patients who become re-infected after one course of Sovaldi would be less likely to be approved for a second course.

Combined, the guidelines would reduce the number of patients eligible for Sovaldi treatment through Medicaid by about 40 percent. To many, this is straightforward rationing — it’s denying patients a clinically helpful treatment. I don’t want to get into most of that debate, especially those around the ethics of the requirements on Medicaid patients.

I did want to point out, however, that there’s at least some reason to think that limiting treatment to those with relatively advanced disease makes sense. New York isn’t the only state to consider this — California and Oregon are also considering versions of this idea. A very significant portion of patients with chronic hepatitis C infection will never display symptoms, and only 20% will progress to end-stage disease. There’s a legitimate argument to be made that patients who don’t have any signs of disease (other than the virus in their blood) should just be carefully watched before spending huge sums of the state’s money on a treatment they might have never needed.

These states are essentially saying that they’ll pay for treatment for patients who really need it, and not patients who don’t. Of course, it’s hard to decide what “true need” is: it could range from testing positive for the virus to mild liver problems only noticed on laboratory results to deeply sick patients on the verge of end-stage liver disease. Then again, when it comes to hepatitis C, treatment is prevention, so there are very good reasons to treat everyone who has the virus. As previously covered, however, the distribution of cost of such widespread prevention is problematic.

The point here is that it’s easy to cry “rationing,” and to be accurate, this is rationing. But so too is rationing by price or waiting times, or any other mediator of access. Sovaldi will continue to be a fascinating test case in how our society deals with tradeoffs — this is hard stuff, and it’s high time we start thinking deeply about it.

*As an aside, it’s actually somewhat difficult to compare “adherence rates” and “discontinuation rates.” Adherence rates measure how many doses are missed in a given time period in which the medication was prescribed, while discontinuation rates measure how many patients completely stopped taking their medication before the course ended (either because their doctor took them off the medication or of their own volition.) Thus, a patient who forgot to take their Sovaldi on Saturday mornings might be nonadherent without discontinuing, while one whose physician took them off the drug due to side effects despite taking every dose as prescribed would be counted as discontinued, even though they were adherent.