Fee for service payment of physicians is often blamed as a contributor to high and rapidly growing health care costs. In an analysis of primary care physicians, Helmchen and Lo Sasso provide a sense of how physicians respond to different compensation schedules:

Using a four-year [2003-2006] sample of 59 physicians and 1.1 million encounters, we study how physicians at a network of primary care clinics responded when their salaried compensation plan was replaced with a lower salary plus substantial piece rates for encounters and select procedures. Although patient characteristics remained unchanged, physicians increased encounters by 11 to 61%, both by increasing encounters per day and days worked at the network, and increased procedures to the maximum reimbursable level.

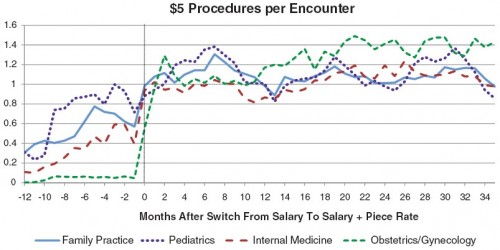

The extra payment that so dramatically increased encounters was $5 for each reported performance of an eligible procedure. The number of procedures per encounter in each month that qualify for the $5 bonus is illustrated in the following figure by practice area:

The policy implication is obvious, right? Paying fee for service is asking for higher costs. So, we could cut costs by reducing or eliminating piece rate based (fee for service) payment. Case closed.

Not so fast! Let’s talk about what those $5 bonus payment eligible procedures were.

[T]he network began paying physicians $5 for each reported instance of most immunizations for children and adults as well as counseling and screening services aimed at detecting or preventing risk behaviors such as substance abuse, contraction of infectious disease, suicide, obesity, and the patient’s exposure to violence. Importantly, physicians were only remunerated for an average of one $5 procedure per encounter.

It is not at all obvious that the extra money spent encouraging these particular procedures was not worth the personal and population health value they conferred. Put it this way, would you argue that the individuals who received those services should not have, that those services were part of the problem of overuse of unnecessary care? That is a hard argument to make. Yet the data show that without the extra $5 the studied physicians provided fewer of those very services.

As the authors point out, to make that precise, one would need to quantify the health gains and adjust for whether the provision of extra services by these physicians didn’t just offset a reduction of services by others for the same patients (crowd out). By doing so, it is possible to make a good argument that more health spending is worth the cost (see my post on Cutler’s book that makes this very argument, but with numbers.) This is important to keep in mind. Fee for service isn’t all bad. It just needs to be applied in a more nuanced way. Not all physician compensation should be fee for service. But some should be.

The Helmchen and Lo Sasso study illuminates another good point.

If physicians’ treatment decisions were guided exclusively by the patient’s clinical condition and treatment preferences, physicians’ practice patterns would be independent of the way they are compensated. Our findings suggest that, at least based on their reports to the network’s administrative database, physicians appear to respond quite stridently to incentives at the margin.

Yep. Money talks. Even for physicians.