Longtime readers of the blog know that I can easily go off on a rant about how survival rates are not the same as mortality rates. Improvements in one do not necessarily mean improvements in the other. Here’s my now-classic example:

Let’s say there’s a new cancer of the thumb killing people. From the time the first cancer cell appears, you have nine years to live, with chemo. From the time you can feel a lump, you have four years to live, with chemo. Let’s say we have no way to detect the disease until you feel a lump. The five year survival rate for this cancer is about 0, because within five years of detection, everyone dies, even on therapy.

Now I invent a new scanner that can detect thumb cancer when only one cell is there. Because it’s the United States, we invest heavily in those scanners. Early detection is everything, right? We have protests and lawsuits and now everyone is getting scanned like crazy. Not only that, but people are getting chemo earlier and earlier for the cancer. Sure, the side effects are terrible, but we want to live.

We made no improvements to the treatment. Everyone is still dying four years after they feel the lump. But since we are making the diagnosis five years earlier, our five year survival rate is now approaching 100%! Everyone is living nine years with the disease. Meanwhile, in England, they say that the scanner doesn’t extend life and won’t pay for it. Rationing! That’s why their five year survival rate is still 0%.

You have to understand that not all cancer is fatal. Many cases might never be detected and might never cause death. But if we screen like crazy, we will pick up those cases, too. Those cancers will be treated, and that can cause both mental and physical sequelae. In other words, we may be causing harm without any actual benefit in terms of saving lives.

There’s a new paper out in BMJ that directly hits this issue. It’s titled, “Preventing overdiagnosis: how to stop harming the healthy“:

Medicine’s much hailed ability to help the sick is fast being challenged by its propensity to harm the healthy. A burgeoning scientific literature is fuelling public concerns that too many people are being overdosed, overtreated, and overdiagnosed. Screening programmes are detecting early cancers that will never cause symptoms or death, sensitive diagnostic technologies identify “abnormalities” so tiny they will remain benign, while widening disease definitions mean people at ever lower risks receive permanent medical labels and lifelong treatments that will fail to benefit many of them. With estimates that more than $200bn (£128bn; €160bn) may be wasted on unnecessary treatment every year in the United States, the cumulative burden from overdiagnosis poses a significant threat to human health.

Narrowly defined, overdiagnosis occurs when people without symptoms are diagnosed with a disease that ultimately will not cause them to experience symptoms or early death. More broadly defined, overdiagnosis refers to the related problems of overmedicalisation and subsequent overtreatment, diagnosis creep, shifting thresholds, and disease mongering, all processes helping to reclassify healthy people with mild problems or at low risk as sick.

The downsides of overdiagnosis include the negative effects of unnecessary labelling, the harms of unneeded tests and therapies, and the opportunity cost of wasted resources that could be better used to treat or prevent genuine illness. The challenge is to articulate the nature and extent of the problem more widely, identify the patterns and drivers, and develop a suite of responses from the clinical to the cultural.

Here’s the money shot:

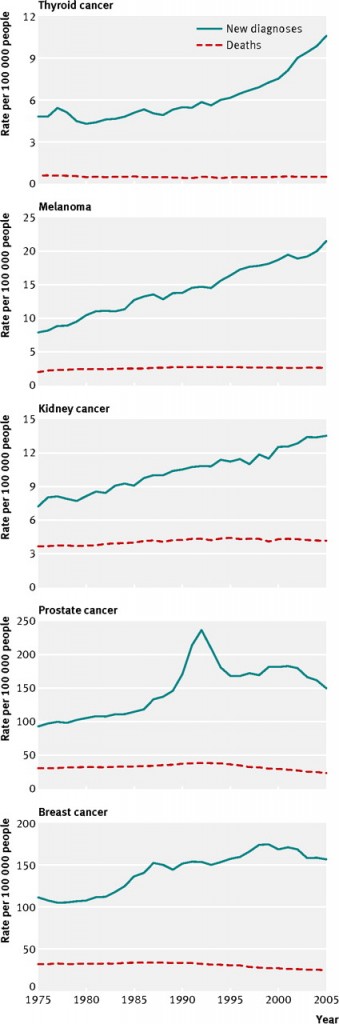

Let me orient you. The blue line represents the number of diagnoses of each type of cancer per 100,000 people. The red line represents the mortality rate for the population for that type of cancer, with deaths per 100,000 people. Data are presented for 1975-2005.

What you’re seeing is a significant increase in diagnoses of these diseases over the three decades. In some cases, the rate of diagnosis has tripled. Now, unless you think something has changed in the world to make cancer way more common, we can likely attribute this increase in the number of cases to the way we practice medicine; it’s due to increased screening and improved detection of disease. But look at the mortality rates. They’re pretty darn stable. This means that although we’re picking up way more disease, we’re not actually preventing a corresponding amount of death.

The simplest explanation for this is that many of the cases of cancer we are detecting might not really benefit from early, let alone any, diagnosis. I’m not denying that there is likely some number of people who benefited from early detection and treatment. But, looking at the above, that number is likely small. I can almost guarantee that all of those diagnosed, however, suffered from life-changing anxiety and fear, not to mention surgery, chemo, and/or radiation.

I won’t even mention the cost.

We have got to do a better job here. We’ve convinced ourselves that when it comes to screening, it’s got to be more, more, more. It’s getting harder to justify that the benefits outweigh the harms.

Go read the whole article. It’s ungated.