This is a TIE-U post associated with Karoline Mortensen’s Introduction to Health Systems (UMD’s HLSA 601, Fall 2012). For other posts in this series, see the course intro.

As a health outcome, mortality has its advantages: apart from zombies, it’s a relatively unambiguous condition, and it’s unambiguously bad. In contrast, hospitalization, even emergency department use, can be good or bad, depending on the circumstances. Mortality has its disadvantages too: it’s a relatively rare event, requiring a long follow-up to observe in large numbers. And, it isn’t representative of the full spectrum of risks we want health care to mitigate. Still, it’s worth knowing the extent to which health insurance affects mortality. As recent events from the presidential campaign trail illustrate, there is some controversy in this area.

It’s hard to know the effect of health insurance on mortality with great precision. One reason is that other things, like poor health and low income, lead to both increased mortality and uninsurance. Worse, not all of those other things are observable, so it’s hard to control for them. One often sees estimates of associations coupled with strained language that is all too easy to interpret as causation. That’s not to say that insurance doesn’t have a causal effect on financial and health outcomes, including mortality. It’s just very hard to estimate the sizes of the causal effects. All this could be addressed with a randomized trial in which people are randomly assigned to insured and uninsured states, but such an experiment is unethical. Clever researchers find other ways around the problem, e.g., the Oregon Health Study.

This week, Mortensen assigned two readings that relate insurance to financial and health outcomes, including mortality: a primer on the uninsured by the Kaiser Family Foundation and a paper on health insurance and mortality by Andrew Wilper and colleagues (PDF). Both are ungated. Apart from my broad comments about association and causation above, instead of discussing either of these documents, I am going to summarize a relatively recent NBER paper that uses a clever technique.

In an August 2012 NBER paper, Bruce Meyer and Laura Wherry applied a powerful statistical approach to the issue of whether Medicaid saves lives.

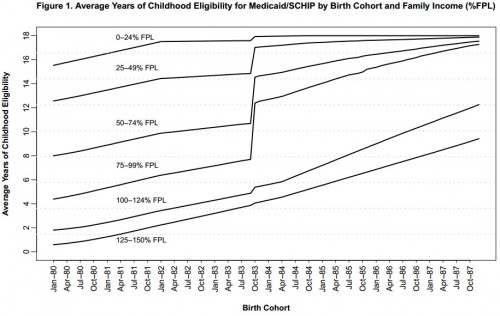

This paper provides new evidence on the mortality effects of expansions in public health insurance eligibility for children in the mid 1980s to early 1990s. Our identification strategy exploits a unique feature of several early Medicaid expansions that extended eligibility only to children born after September 30, 1983. This feature led to a large cumulative difference in public health insurance eligibility for children born on either side of this birthdate cutoff. Children in families with incomes at or just below the poverty line gained close to five additional years of eligibility if they were born in October 1983 rather than just one month before. Black children were more likely to be affected by the Medicaid expansions and gained twice the years of eligibility on average as white children at this birthdate cutoff. The average gain in eligibility also varied by state of residence due to differences in state Medicaid eligibility rules prior to and during the expansions, as well as differences in the demographic characteristics of state residents.

The authors are exploiting a discontinuity in children’s Medicaid eligibility. The intuition is that there is no reason to believe that kids born just before the September 30, 1983 cutoff are different from those born just after: there are no relevant, unobservable factors. A before/after cutoff date indicator is akin to a random flip of a coin. Broadly, your understanding of randomized controlled trials applies. The following chart shows the discontinuity in action.

The authors argue that this regression discontinuity design is stronger than relying on state variation in Medicaid eligibility, the main technique in many of the studies on Medicaid outcomes I’ve reviewed on this blog.

We should emphasize that this source of variation in Medicaid eligibility is not as clearly exogenous as birthdate. States with improving child mortality may be less likely to expand coverage, for example.

The study results are nuanced.

The results provide strong evidence of an improvement in mortality for black children under the Medicaid expansions. Although there is some evidence of a decline in mortality rates during the period of coverage (ages 8-14), we find a substantial decline in the later life mortality of black children at ages 15-18. The regression estimates indicate a 13-18 percent decrease in the internal mortality rate of black teens born after September 30, 1983. Because deaths due to internal causes are more likely to be influenced by access to medical care, this result supports an improvement in the underlying health of black children under the eligibility expansions. Early evidence indicates that this gain in health is not reversed during the early adult years. We find no evidence of an improvement in the mortality of white children under the expansions. Furthermore, we are unable to detect mortality improvements among children residing in those states with the largest gains in public health insurance eligibility under the expansions.

Why wouldn’t mortality improvements be larger in states with larger gains in public health insurance eligibility? The authors explanation boils down to, eligibility isn’t everything:

One potential explanation for this result is that larger expansions in eligibility do not directly translate into higher levels of enrollment or improvements in access to medical care for children. Increases in enrollment require outreach by states and the dissemination of eligibility information to parents. In addition, larger numbers of new beneficiaries may strain limited supply-side resources, particularly if physicians opt not to accept Medicaid clients due to low reimbursement rates or slow payment.

Readers particularly interested in this subject should also be familiar with the recent article by Sommers, Baicker, and Epstein. See also the FAQ on the effects of health insurance on health.

UPDATE: Added explanation for why there were no observed mortality improvements in states with the largest health insurance eligibility.