What happens to children when their parents lose their jobs? My intuition is that job losses stress families and put children at increased risk of child abuse. But Jason Lindo, Jessamyn Schaller, and Benjamin Hansen have surprising data saying that the answer is more interesting than that.

Previous data suggested that my intuition was wrong and that hard economic times have little influence on child abuse. For example,

Despite the onset of our most recent recession and the declines in family income that followed, victimization rates have actually fallen slightly from 2007 to 2010 (from 9.6 per 1,000 children to 9.2 per 1,000 children)…

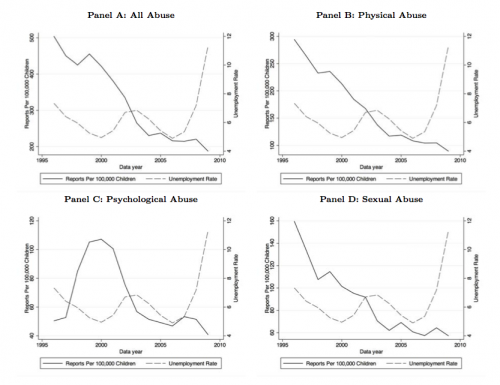

The graph below shows the association between unemployment in California (the broken lines) and four measures of officially-reported child abuse (the solid lines).

Notice, for example, how unemployment rockets up starting in 2007, but child abuse rates do not. (This lack of association may have occurred in part because the recession reduced the ability of the state to find and report child abuse. However, I don’t think this was a threat to Lindo’s analyses.)

The authors took a fresh look at the issue of unemployment and child abuse using California county data from 1996 to 2009. The problem with looking at the simple correlation between unemployment and child abuse is that many other factors, most of them unmeasured, affect both variables. So what Lindo and colleagues did was to look at county-specific fluctuations in unemployment and child abuse. A county-specific fluctuation is how, for example, 2005 unemployment in Los Angeles County deviated from both historical LA County unemployment levels and 2005 California-wide levels. Lindo and colleagues reasoned that local deviations for unemployment (or child abuse) in a specific county and year would be relatively uncontaminated by trends in other social factors. And therefore if they found that local upticks in unemployment corresponded to local upticks in child abuse, this would be strong evidence that increased unemployment causes child abuse.

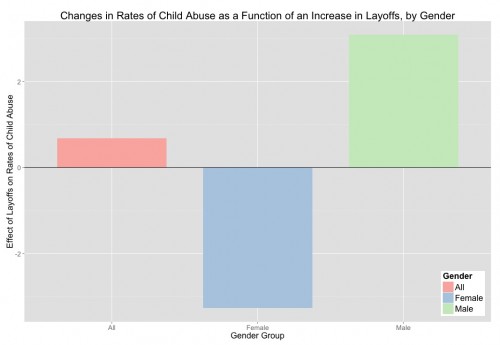

In the graph below, the vertical axis is the percentage increase in county-specific child abuse associated with a 0.1% increase in county-specific layoffs.

The pink bar on the left represents a 0.68% increase in child abuse associated with layoffs of all workers. This increase was so small that it was not statistically different from zero. The blue and green bars, however, are the effects of layoffs of female and male workers respectively. They show that

a 0.1% increase in the fraction of working-age males being laid off leads to a 3.09% increase in the number of reports of abuse. In contrast, the point estimates imply that 0.1% increase in the fraction of working-age females being laid off leads to a 3.27% reduction in the number of reports of abuse. [Emphasis added, both effects statistically significant.]

So layoffs have large and opposite effects on child abuse, depending on whether men or women are laid off.

Lindo and colleagues have a plausible explanation for this. Female layoffs increase the proportion of time children are with mom. Male layoffs increase the proportion they are with dad. Both genders abuse children, but a man is about three times more likely to abuse on a per hour basis than a woman.

So much for my intuitions: I thought the story was about stress, but it is also about time and gender. This study tells us to look at how the effect of a treatment or a risk factor varies depending on the person it is applied to. This is why research study populations should be as diverse as is practicable. When it makes sense, we should include both adults and children, or men and women, and carry out the analyses that look for heterogeneity of effects. This is the motivation behind personalized medicine: finding out what works for whom.

The policy upshot of some previous research on unemployment and child abuse was that although reducing unemployment is a very good thing, it probably won’t do much to reduce child abuse. This study doesn’t change that conclusion. But it does suggest that we need to do a better job of socializing men to be authoritative, effective, and non-abusive parents.