The following is a guest post by Allan Joseph, a medical student at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University and TIE research assistant. You can follow Allan on Twitter: @allanmjoseph or email him. This post is part of a series on the Institute of Medicine’s report on graduate medical education (GME), which you can follow with the tag IOM on GME.

In my previous posts prompted by the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM’s) report on GME, I discussed physician shortages. In this post, I’m going to get to perhaps the most controversial topic in GME policy: how governmental GME funding affects the supply of physicians. As a refresher, remember that GME costs taxpayers $15 billion each year, two-thirds of which is administered by Medicare, with the remainder from Medicaid and other programs. For more background, read this Health Affairs policy brief or the executive summary of the IOM report, linked above.

Let’s start with an informal statement of the theoretical argument for subsidizing GME: without a subsidy*, hospitals would not find graduate education sufficiently profitable** to open enough residency slots required to produce a sufficient physician workforce.

There are undoubtedly substantial costs associated with training residents: both the obvious costs of teaching, resident salaries, and program administration and the other costs that come because residents (as new doctors) tend to work more slowly and inefficiently than fully-trained attending physicians. (More about indirect costs in the subsequent post.)

But to assess accurately whether training residents might be unprofitable for hospitals, you have to consider not just the costs, but also the revenue generated by a resident physician. After all, private insurers and public programs reimburse the hospital for services provided, whether by a resident or a fully trained doctor. To assess whether hospitals earn positive net revenue from residents, researchers have watched their behavior when GME funding policies change.

One big change took place in 1997, when the Balanced Budget Act (BBA) capped the number of residency slots for which Medicare would pay at any given hospital, though hospitals were free to add new slots that Medicare wouldn’t pay for. It was a soft cap with some exceptions, but it applied to most hospitals in most cases.

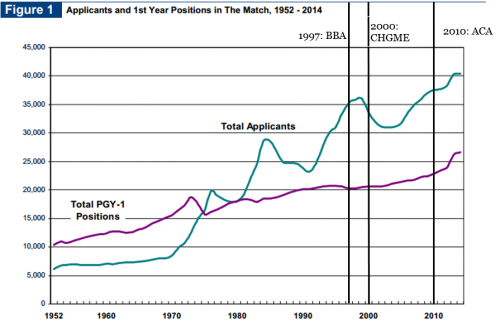

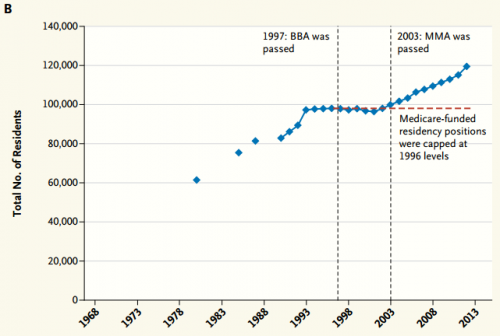

Take a look at these two graphs to assess the impact of the cap. Figure 1 is from the 2014 report by the Match (the organization which matches applicants with residencies) describing the openings for first-year residents (“PGY-1 positions”) and the number of applicants for those positions, with my annotations. The other is from the New England Journal of Medicine, depicting the total number of residents:

(For reference, “MMA” refers to the Medicare Modernization Act, which made minor changes to GME but is best known for instituting Medicare Part D.)

The graphs tell a very different story than the theory that hospitals cannot afford to train physicians without GME funding. If the theory is to be believed, hospitals would have maintained their residency programs at the same levels, or perhaps even cut them as inflation ate away at the cap. Put another way, if residencies were money-losers that needed to be subsidized, the pro-subsidy argument says that capping the subsidy would also cap the number of residency slots.

Yet the number of slots increased steadily after the BBA, both for incoming residents and for the total number of residents — over 20% for incoming residency slots and about a 17% increase in the total number. It’s not a smoking gun, but it does strongly suggest that even without Medicare funding for additional residencies, hospitals found that adding residents was in their interest (probably profitable).

So is that it? Is GME funding superfluous, because training residents is a profitable endeavor for hospitals anyway? Well, the story gets more complicated, because Medicare isn’t the only source of GME funding — as I said above, it accounts for only two-thirds of GME funding. Medicaid is the next biggest source at about $4 billion, which has increased by about $500 million since 1998. Other funding sources such as the Children’s Hospital GME (CHGME) program and ACA have added another $300 million in that same time period. (All dollar amounts are adjusted to 2013 dollars.)

Since Medicare’s GME spending has fallen by $1.2 billion since 1997, there’s been a net decrease in GME funding of about $400 million, or 2.8%, since the BBA. That analysis doesn’t include the VA, which has also increased its funding for GME programs, but I couldn’t find the numbers on how much. Given that Medicare and Medicaid account for the vast majority of GME funding, however, the VA increases are likely negligible. Therefore, other funding sources can’t explain the increase.

There are two more arguments in favor of GME subsidies to consider. First, it’s possible that residencies in some specialties are profitable and others aren’t, especially since residents in a hospital make the same salary regardless of their specialty. For example, residents in surgical or procedural specialties might bring in far more revenue than those in primary care. If that’s the case, the residencies added since the BBA may have only been in profitable specialties, since unprofitable specialties would no longer have been subsidized. One might argue for GME to prop up the less profitable specialties, for example.

The data I’ve found that might support this argument are mixed. The Match reports a list of specialties that have increased their slots by over 10% since 2010 in its data report. That list includes anesthesiology, emergency medicine, plastic surgery, general surgery, thoracic surgery, and vascular surgery — relatively high-billing specialties that could be more profitable. But it also includes family medicine, internal medicine, and pediatrics — the three primary care specialties. Now, that doesn’t reflect what happened between 1998 and 2010, but on this basis alone, I’d have to be moderately skeptical of the argument that hospitals have only increased profitable slots.

The second additional argument in favor of GME funding is summarized by the phrase “diminishing marginal returns.” In this explanation, hospitals might find adding some residents profitable, but only to a point. At some point, adding more residents might mean increased costs (more faculty) or decreased revenue (there’s only so many surgeries for residents to perform). For a completely hypothetical example, it might make financial sense for a hospital to go from 50 to 75 residents per class, but it might not make sense to have a 150-resident class.

If the financially-optimal number of residents for a hospital is lower than the socially-optimal number (however we might determine that), then that might be a reason to subsidize residency slots. However, the difficulty in accounting for residents’ share of revenue and costs means there’s little evidence beyond theoretical reasons to support this argument.***

The theoretical argument in favor of GME to maintain the profitability of hospital-provision of training for residents is on some very weak ground here. The available evidence strongly suggests that increases in GME funding are unnecessary for significant increases in GME slots. It’s not bulletproof by any means, but it’s the best we’ve got.

Despite all of that, there might be other reasons to support GME funding (though maybe not its name). We’ll get to those next.

* We’re using “subsidy” here broadly — some people object to the term, but I think it’s the best one for a governmental payment related to medical education. In addition, we’ll treat Medicare’s two funding streams as a single functional unit — though they differ in funding formulas and stated purpose, we’ll simplify and treat them as one payment. Money is fungible, after all.

**”Profitable” here refers to something that simply brings in more money than it costs. Most teaching hospitals are nonprofit institutions, but that’s doesn’t mean they’ll operate at a financial loss.

***Plus, you’d have to believe the labor market for residents has some failures to buy this explanation.