There’s much wonderful reporting in Monica Davey’s front-page New York Times’ piece on Chicago’s current homicide challenge. But I hate the headline: “In a Soaring Homicide Rate, a Divide in Chicago.” To be more precise, I hate the first half of the headline. The second half is right on the money.

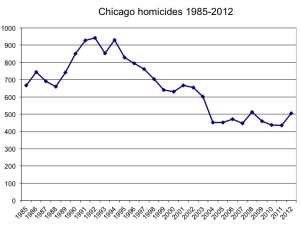

Why do I hate the headline? Below is the piece’s missing graph: Chicago homicides 1985-2012.

It’s obvious from the graph that the city’s homicides displayed a disturbing uptick. 2012 displayed an almost 20% increase over 2011.

That’s a serious concern. I co-direct the University of Chicago Crime Lab. We received many calls from reporters the night Chicago reported its 500th homicide two weeks ago.

Without in any way diminishing the seriousness of the issue, I would emphasize that our homicide rate last year was far below Chicago’s rate in any year between 1985 and 2002. We had almost twice that homicide rate in the worst years of the crack epidemic. Chicago experienced a high homicide rate during the first quarter of 2012. Rates were quite similar to the past several years for the rest of the year.

Chicago is in the middle of the pack when compared with the broad swathe of American metropolitan areas. Chicago ranks 79th on Neighborhood Scout’s list of the 100 most dangerous places to live in America. Chicago does not earn a place in the various “top ten” lists of the most dangerous cities in America….

Chicago does have markedly higher homicide rates than Los Angeles or New York. We have more homicides than New York, although New York is more than twice the size. That’s a big problem. Still, the idea that Chicago faces a unique or unprecedented rise in homicides is incorrect. Our problems are all too familiar and chronic throughout much of urban America. No one in Milwaukee, Cleveland, Detroit, Buffalo, or Houston would be very surprised by what’s happening in Chicago’s highest-crime communities.

Here’s where Davey’s reporting is right on the money. She depicts quite accurately the human face of an ongoing tragedy. The Times multimedia displays remarkable disparities across Chicagoland. Residents of Lincoln Park and other prosperous neighborhoods live in levels of physical safety rather comparable to western European cities. Meanwhile, young people across much of Chicago’s south and west sides endure real dangers and heartbreaking conditions of hopelessness that extend far beyond the stark homicide statistics that make the front page. Working in these communities, I’m struck by just how hard it is to be a 17-year-old kid in Chicago.

Our nation recently committed hundreds of billions dollars because it was unthinkable to allow our financial system to collapse. We’ve shown a conspicuous lack of similar urgency in addressing the human problems these young people face: not just the violence, but also widespread joblessness, poverty, home foreclosures, and public heath problems in these same hard-hit communities.

There’s much we can do to reduce homicides and violence in Chicago—and in many other places. We can do a better job helping young people develop academic and social-emotional skills. We can get a better handle on illegal gun markets, gun possession, and use. We can do a better job addressing truancy and educational failures. We can support state and local efforts to put more cops on the street—and to deploy cops on the dots where crimes actually occur. We can provide better substance abuse and mental health treatment services.

Much of this work requires methodical, evidence-based work to determine which interventions are most effective, for whom, and at what cost-effectiveness. We need the right mix of patience and urgency in doing this work. Davey’s story does a great service by showing the human face of violence in a great city.

We spend huge amounts of money on crime prevention, law enforcement, and other aspects of the criminal justice system. We know far less than we should about the return on these investments. The University of Chicago Crime Lab website contains more information on promising strategies.

Barring late-changes, I’ll be one of tomorrow’s guests on Up with Chris Hayes discussing crime issues. Yeah I’m a little nervous.