The following was originally posted on the AcademyHealth blog earlier this year.

Long understood by some clinicians and policymakers, there is growing awareness of America’s opiate use crisis, and renewed efforts to do something about it.

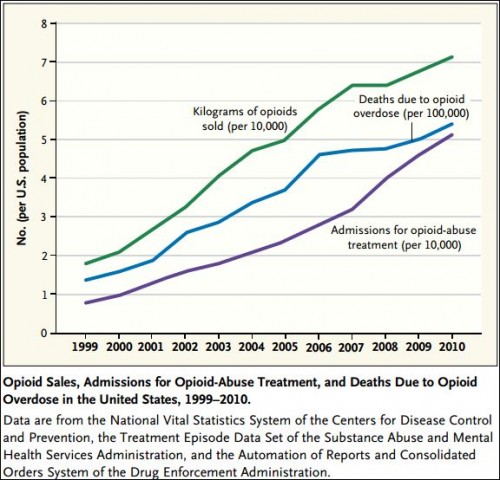

A few statistics serve to make the case that use of opioids is a serious problem in the U.S.: Opioid use is now the leading cause of substance use-related ambulatory visits. The number of fatal drug overdoses doubled between 1999 and 2010; deaths from opioid pain relievers account for most of that increase, quadrupling between 1999 and 2010. Overdose deaths are the leading cause of accidental death in the U.S., exceeding those from motor vehicles. As if loss of life weren’t alarming enough, abuse of opioids costs a lot of money too: prescription opioid abuse costs were about $72.5 billion in 2007, and patients abusing opioid analgesics cost insurers about $14,000 more than average patients between 1998-2002.

(Source: Nora Volkow et al.)

Of course, my state of residence—Massachusetts—and its neighbors are not immune to the growing opioid abuse problem. According to the Alanna Durkin, reporting for the Associated Press, in Maine, deaths from heroin overdoses quadrupled from 2011 to 2012; in New Hampshire the number of such deaths doubled from 2012 to 2013; in Vermont they doubled recently as well. New England governors suggested approaches to addressing this growing epidemic. Proposed solutions often include enhancing treatment programs and “hunt[ing] down drug dealers.”

These numbers serve to shock, but they do not address the pervasive misunderstandings of drug use and abuse in general and the opioid problem in particular. An insightful conversation between Harold Pollack and Keith Humphreys illuminated some hard truths. A few highlights:

- Substance use disorders are not confined to Hollywood stars or the poor. Most people with drug problems have jobs; a huge proportion are “nice, middle class people.” They are your neighbors, friends, family members, coworkers, or you.

- Though deaths due to drugs now rival those from AIDS at the peak of its epidemic, unlike the early outbreak of AIDS, substance use is not focused within a “pre-existing community of people. […] It’s spread all over.”

- Detox that isn’t “followed up with careful interventions and monitoring” have relapse rates close to 100%. There are no quick fixes here.

- Most opiate overdose deaths and growth in them can be traced back to prescriptions: “4 in 5 of people today who start using heroin began their opiod addiction on prescription opioids.” Clamping down on the supply of heroin alone will not address the problem.

- U.S. clinicians “write more prescriptions for opiate painkillers each year than there are adults in the United States.” Think about that.

The health system itself plays a large role in the problem, and should be part of any solution. Recent work by Christopher Jones and colleagues, published in JAMA Internal Medicine, shows that while friends and relatives are the predominant, proximate source of opioid analgesics used for nonmedical purposes, about 20% are directly prescribed by physicians, the second most common source (others being stolen or bought from friends or relatives, bought from a drug dealer or stranger, and other). However, almost all opioid analgesics begin with a prescription, even if they’re later transferred by sale or theft.

What can be done? A full answer takes far more space than one post, and I’ll come back to it later (stay tuned). Ways to address the problem include alternative pain management, adjustments to prescribing practices, and expansion of access to a wider range of longer-term addiction treatment programs.

Responding to the overprescribing of opiate-based painkillers, in July 2012 Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts attempted to change prescribing patterns. It began requiring prior authorization for more than a 30-day supply within a two-month period. After 18 months, the insurer estimates that it cut prescriptions of opiate painkillers by 6.6 million pills.

In addition to attacking the problem on the front-end, there’s another way to save lives from the opioid epidemic. Better access to and protections for use of naloxone—an opioid agonist—could prevent death from overdose. Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick recently made naloxone (brand name: Narcan) more available to first responders and to families and friends of drug abusers. Other states have already taken similar measures to promote life-saving naloxone use. Maine Governor Paul LePage is considering reversing his opposition to allowing health care providers prescribe naloxone to opioid addicts’ family members and allowing them to deliver it as required.

To better understand what’s known about options to manage opiate dependence, the New England Comparative Effectiveness Public Advisory Council (CEPAC)* will hold a public meeting to consider the relevant evidence and how it applies to New England patients, payers, and providers. I will summarize findings in a future post.

* I am a member of CEPAC. [This meeting has now been held. Details here.]