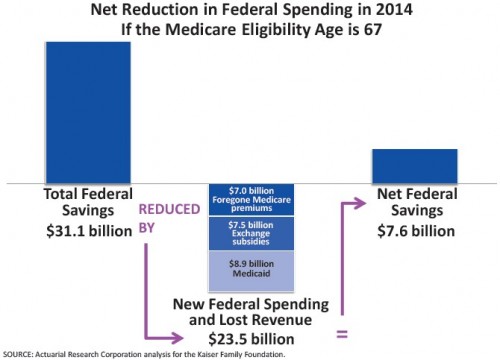

The Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) has released a report about the budgetary impact of raising the age of Medicare eligibility to 67. If you think it’s a great way to save a lot of money, it isn’t according to KFF and the actuaries the organization worked with to produce the report. As the following figure shows, the total gross savings is just over $31 billion. Once you factor in what those 65 and 66 year olds would do after losing Medicare eligibility, the net savings is only $7.6 billion. The analysis is for the year 2014 so health reform is largely implemented (the exchanges and subsidies exist as of that year).

What’s $7.6 billion? To put it in perspective, the annual cost of the Medicare program was about $600 billion in 2010. Thus, $7.6 billion is only 1.2% of that total. And this is an overestimate in percentage terms because the program will cost much more in 2014, the year for which the $7.6 billion was figured. That small an amount of savings will be wiped out by much less than one year of typical inflation of health care costs. It’s quite modest, to say the least. By itself, raising the age of Medicare eligibility does next to nothing in addressing the cost of health care.

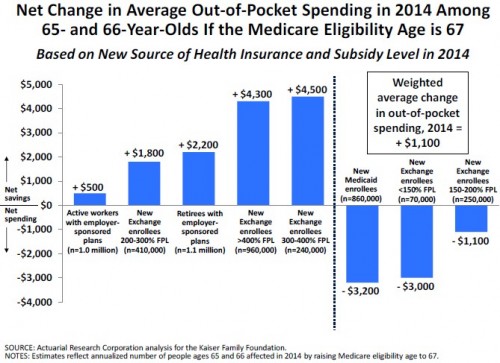

The report also documents how some of costs that would have been borne by Medicare for 65 and 66 year olds. In the following figure positive numbers mean higher out-of-pocket costs if the eligibility age were increased. On average, a 65 or 66 year old would pay $1,100 more relative to Medicare as we know it.

Thus, increasing the age of eligibility would change how income is redistributed. It would cause the average 65 or 66 year old to pay more than he or she otherwise would, though, as the above chart shows, it actually helps very low income individuals in that age range.* Still, it’s a funny way to determine who bears what portion of the costs of health care. If we’re concerned about who pays what, then the focus should be on, well, who pays what, not what age groups qualify for what program.

This suggests a point that Harold Pollack raised yesterday, that the balance of taxation and benefits for affluent seniors, not to mention the rest of us, may need some reexamination.

Any reasonable solution [to entitlement reform] should include a closer look at the tax breaks we give to affluent seniors.

Elizabeth McNichol of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities has done important work on state tax preferences for seniors. Measures differ across the states, but include property tax reductions, exclusion of pension and Social Security income from state income taxes, and more. These tax expenditures are typically poorly-targeted. They also cost states billions of dollars every year.

At the federal level, these tax expenditures are even larger. The estate tax issue gets greatest play, but the tax code is larded with many other items that allow upper-middle-class and affluent seniors to avoid some or all taxes they really should pay. […]

We have real intergenerational equity issues, too. Accounting for investment returns and the like, current retirees receive substantially more than they have contributed to finance public social insurance systems. Particularly in the case of Medicare, the lifetime actuarial subsidy is surprisingly large, often exceeding $100,000. […] Many seniors are also shielded from our current macroeconomic traumas in a way that young people are not.

If we were to seriously consider adjustments to Medicare that redistribute income in a way that differs from how Medicare currently does so, then that suggests we are open to redistributing income in a way that differs from how Medicare currently does so. If that’s the case, let’s look at it. Do we find the balance of costs and benefits to be fair and equitable? Is there something about the change in distribution in the figure above we like better? Why? Why not?

More broadly, this gets to something I’ve raised before. The real problem with health care costs may not be their level or even their rate of increase. One can view those as problems, but one can also view them as evidence of the value we place on health care. Whether problematic or not, health costs will likely out-pace the economy for the foreseeable future. Thus, independent of how you view the level and rate of increase, one must address how those costs are distributed. Who receives the benefit and who pays for it? It’s a tough question. Yet technically, though not politically, reforming how costs and benefits are distributed is far simpler than curbing the growth of health care costs.

* There are other effects I’m not mentioning, but the report is ungated and has an executive summary so read for yourself.