The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2018, The New York Times Company). Research for this piece was supported by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation.

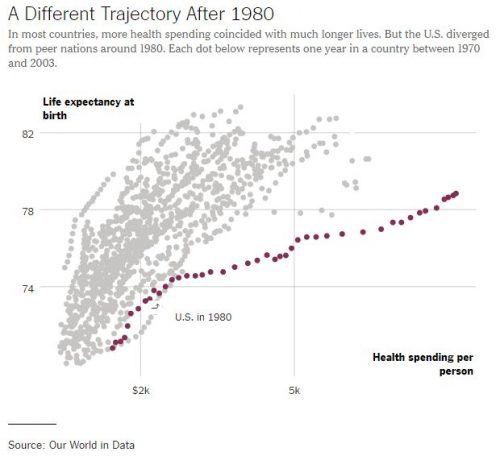

The United States devotes a lot more of its economic resources to health care than any other nation, and yet its health care outcomes aren’t better for it.

That hasn’t always been the case. America was in the realm of other countries in per-capita health spending through about 1980. Then it diverged.

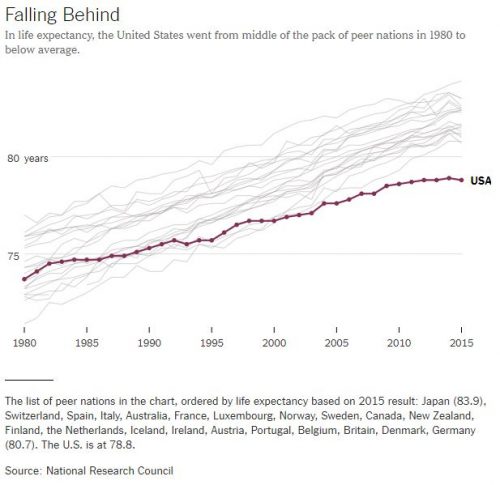

It’s the same story with health spending as a fraction of gross domestic product. Likewise, life expectancy. In 1980, the U.S. was right in the middle of the pack of peer nations in life expectancy at birth. But by the mid-2000s, we were at the bottom of the pack.

What happened?

Health spending and life expectancy are not necessarily closely related, so it’s helpful to consider them separately.

“Medical care is one of the less important determinants of life expectancy,” said Joseph Newhouse, a health economist at Harvard. “Socioeconomic status and other social factors exert larger influences on longevity.”

For spending, many experts point to differences in public policy on health care financing. “Other countries have been able to put limits on health care prices and spending” with government policies, said Paul Starr, professor of sociology and public affairs at Princeton. The United States has relied more on market forces, which have been less effective.

“Confronted with fiscal pressures, as the share of G.D.P. absorbed by health care spending began to get serious, other nations had mechanisms to hold down spending,” said Henry Aaron, a health economist with the Brookings Institution. “We didn’t.”

One result: Prices for health care goods and services are much higher in the United States. Gerard Anderson, a professor at Johns Hopkins and a lead author of a Health Affairs study on the subject, emphasized this point. “The differential between what the U.S. and other industrialized countries pay for prescriptions and for hospital and physician services continues to widen over time,” he said. Other studies also support this idea. However, by some measures, growth in the amount of health care consumed has also been a factor.

The degree of competition, or lack thereof, in the American health system plays a role. A recent study by economists at the University of Miami found that periods of rapid growth in U.S. health care spending coincide with rapid growth in markups of health care prices. This is what one would expect in markets with low levels of competition.

Although American health care markets are highly consolidated, which contributes to higher prices, there are also enough players to impose administrative drag. Rising administrative costs — like billing and price negotiations across many insures — may also explain part of the problem.

The additional costs associated with many insurers, each requiring different billing documentation, adds inefficiency, according to the Harvard health economist David Cutler. According to a recent study, the United States has higher health care administrative costs than other wealthy countries.

“We have big pharma vs. big insurance vs. big hospital networks, and the patient and employers and also the government end up paying the bills,” said Janet Currie, a Princeton health economist. Though we have some large public health care programs, they are not able to keep a lid on prices. Medicare, for example, is forbidden to negotiate as a whole for drug prices, as Ms. Currie pointed out.

But none of this explains the timing of the spending divergence. Why did it start around 1980?

Mr. Starr suggests that the high inflation of the late 1970s contributed to growth in health care spending, which other countries had more systems in place to control. Likewise, Mr. Cutler points to related economic events before 1980 as contributing factors. The oil price shocks of the 1970s hurt economic growth, straining countries’ ability to afford health care. “Thus, all across the world, one sees constraints on payment, technology, etc., in the 1970s and 1980s,” he said. The United States is not different in kind, only degree; our constraints were weaker.

Later on, once those spending constraints eased, “suppliers of medical inputs marketed very costly technological innovations with gusto,” Mr. Aaron said. They “found ready customers in hospitals, medical practices and other entities eager to keep up with rivals in the medical arms race.”

The last third of the 20th century or so was a fertile time for expensive health care innovation. Sherry Glied, an economist and a dean at New York University, offered a few examples: “Coronary artery bypass grafting took off in the mid-to late 1970s. Later, we saw innovations like drug treatments for H.I.V. and premature babies.”

These are all highly valuable, but they came at very high prices. This willingness to pay more has in turn made the United States an attractive market for innovation in health care.

Yet being an engine for innovation doesn’t necessarily translate into better outcomes. Almost no matter how it’s measured, longevity in the United States has not kept pace with that of other nations. Again, the inflection point is around 1980. Why?

A study examining the period 1975 to 2005 by Ms. Glied and Peter Muennig, from Columbia, suggests that international differences in rates of smoking, obesity, traffic accidents and homicides cannot explain why Americans tend to die younger.

Some have speculated that slower American life expectancy improvements are a result of a more diverse population. But Ms. Glied and Mr. Muennig found that life expectancy growth has been higher in minority groups in the United States. Another study, published in JAMA, found that even accounting for motor vehicle traffic crashes, firearm-related injuries and drug poisonings, the United States has higher mortality rates than comparably wealthy countries.

The lack of universal health coverage and less safety net support for low-income populations could have something to do with it, Ms. Glied speculated. “The most efficient way to improve population health is to focus on those at the bottom,” she said. “But we don’t do as much for them as other countries.”

The effectiveness of focusing on low-income populations is evident from large expansions of public health insurance for pregnant women and children in the 1980s. There were large reductions in child mortalityassociated with these expansions. “Those reductions were much larger for poor children than for richer children,” Ms. Currie said.

A report by RAND shows that in 1980 the United States spent 11 percent of its G.D.P. on social programs, excluding health care, while members of the European Union spent an average of about 15 percent. In 2011 the gap had widened to 16 percent versus 22 percent.

Although this is a modest divergence over time, Mr. Anderson says it could be significant nonetheless. “Social underfunding probably has more long-term implications than underinvestment in medical care,” he said. For example, “if the underspending is on early childhood education — one of the key socioeconomic determinants of health — then there are long-term implications.”

Slow income growth could also play a role because poorer health is associated with lower incomes. “It’s notable that, apart from the richest of Americans, income growth stagnated starting in the late 1970s,” Mr. Cutler said.

Even if we can’t fully explain why the United States diverged in terms of health care spending and outcomes after 1980, one thing is clear: History demonstrates that it is possible for the U.S. health system to perform on par with other wealthy countries. That doesn’t mean it’s a simple matter to return to international parity. A lot has changed in 40 years. What began as small gaps in performance are now yawning chasms. And, to the extent greater American health spending has spurred development of valuable health care technologies, we may not want to trade away all of our additional spending.

Nevertheless, Ashish Jha, a physician with the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the director of the Harvard Global Health Institute, is hopeful: “For starters, we could have a lot more competition in health care. And government programs should often pay less than they do.” He added that if savings could be reaped from these approaches, and others — and reinvested in improving the welfare of lower-income Americans — we might close both the spending and longevity gaps.