From JAMA Internal Medicine, “Effect of Published Scientific Evidence on Glycemic Control in Adult Intensive Care Units“:

Importance Little is known about the deadoption of ineffective or harmful clinical practices. A large clinical trial (the Normoglycemia in Intensive Care Evaluation and Survival Using Glucose Algorithm Regulation [NICE-SUGAR] trial) demonstrated that strict blood glucose control (tight glycemic control) in patients admitted to adult intensive care units (ICUs) should be deadopted; however, it is unknown whether deadoption occurred and how it compared with the initial adoption.

Objective To evaluate glycemic control in critically ill patients before and after the publication of clinical trials that initially suggested that tight glycemic control reduced mortality (Leuven I) but subsequently demonstrated that it increased mortality (NICE-SUGAR).

Design, Setting, and Participants Interrupted time-series analysis of 353 464 patients admitted to 113 adult ICUs from January 1, 2001, through December 31, 2012, in the United States using data from the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation database.

Main Outcomes and Measures The physiologically most extreme blood glucose level on day 1 of ICU admission defined glycemic control as tight control (glucose level, 80-110 mg/dL; to convert to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0555), hypoglycemia (glucose level, <70 mg/dL), and hyperglycemia (glucose level, ≥180 mg/dL). Temporal changes in each marker were examined using mixed-effects segmented linear regression.

So here’s the deal. Some years ago, a study came out which said that there was a benefit to keeping people in the intensive care unit under tight glycemic control. This meant that we had to monitor people’s glucose levels closely and keep them between 80 and 110 mg.dL. The rationale for this is based on lab data and observational studies that showed that having tight control was associated with less hyperglycemia, fewer infections, and a greater chance of survival.

When a large randomized controlled trial was finally done, it showed that providing tight glycemic control to mostly surgical patients in ICUs led to 1 life saved for every 29 patients treated. That’s pretty awesome. So this became recommended practice.

Of course, this being medicine, soon we were providing tight glycemic control not only to critically ill surgical patients, but also non-surgical patients. Cause that’s what we do.

Later, another study was done, called the Normoglycemia in Intensive Care Evaluation and Survival Using Glucose Algorithm Regulation (NICE-SUGAR) study. This was the biggest multinational RCT to examine tight glycemic control in a varied cohort of medical and surgical ICU patients. It showed that tight glycemic control increased (not decreased) the risk of severe hypoglycemia and increased 90-day mortality.

Needless to say, these new data made everyone pause. They also led to some big changes in international guidelines modifying their recommendations for the management of blood glucose in critically ill patients. The original study showing a benefit was published in 2001. The bigger study showing harm was published in 2009.

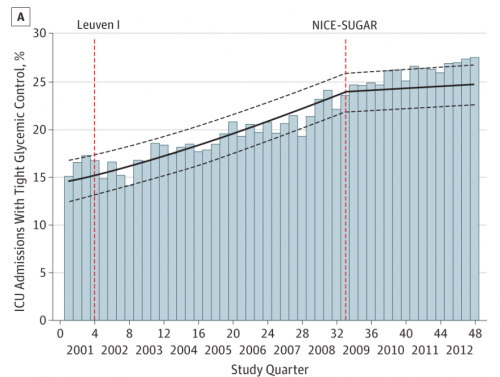

This research looked at how practice changed before and after the publication of the first study and the second study from January 1, 2001 through December 31, 2012.

So before the publication of the first trial, about 17% of admissions to the ICU had tight glycemic control, 3% had hypoglycemia, and 40% had hyperglycemia. After publication of the first trial, each quarter there were 1.7% more increases with tight glycemic control, 2.5% more with hypoglycemia, and 0.6% fewer with hyperglycemia.

This is consistent with what we’d expect a slow, but steady adoption of tight glycemic control to do.

However, after the publication of the second trial, there was no change in the percent of patients with tight glycemic control or hyperglycemia. Here’s how tight glycemic control changed over time:

There are a few things worth noting here. The first is that it is hard to change physician behavior. Even with the first trial, it took years for people to adopt the use of tight glycemic control. But what’s even more important to see is that as hard as it is to get them to do something, it may be even harder to get them to stop doing something.

Tight glycemic control is more involved; it requires more activity, more intervention. It feels like you’re caring for patients. Regular monitoring, especially after years to tight glycemic control, feels like ignoring patients and leaving them in danger. It’s harder to do.

We can’t ignore this. It’s why Choosing Wisely exists. We spend too much time talking about the things we should do, and too little focused on the things we should stop doing.

Unfortunately, doing more often does harm. It also usually costs more money. There’s very little incentive for industry to encourage this type of research. It’s a public good, and we’ve got to invest public money in it.