By Chapter 4 of The Cost Disease Baumol has explained the key concept several times. Nevertheless, he does so again:

Trash removal costs go up not because garbage collectors become less efficient but because less labor is needed to manufacture a single computer, for instance, and wages in that industry (and others, as well) continue to climb. Although the sanitation worker’s productivity is barely increasing, her wages must go up in order to keep her at her garbage removal job—otherwise, she might be tempted to join the computer assembly line. Productivity growth in some sectors of the economy—and the wage increases that accompany it—thus raises the cost of garbage removal and other personal services.

Here, Baumol has added one more step in his chain of logic. The garbage collector’s wages rise even though her productivity has not because if they don’t she’ll find something else to do. We still need garbage collected, though, so if a more lucrative occupation existed for every possible garbage collector who might serve us, we would have no choice but to pay more for trash removal. This is the source of increased cost, the cost disease.

Productivity growth makes a society wealthier, not poorer, and able to afford more of all things—televisions, electric toothbrushes, and cell phones, as well as medical care, education, and other services. This outcome is particularly likely, given the impressive speed at which overall productivity is increasing, relative to the costs of personal services.

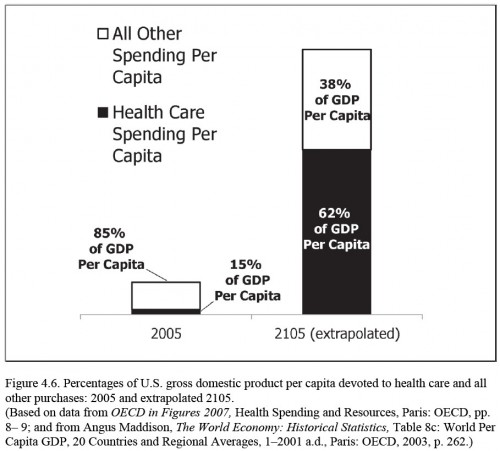

Baumol then demonstrates the awesome productivity growth we’ve experienced in the past century. Extrapolating recent trends, he arrives at the chart below, which is worth understanding, so I’ll explain it slowly. On the left, year 2005 GDP per capita is broken down into that spent on health care (15%) and that spent on everything else (85%). On the right, the same is shown extrapolated out to year 2105. However, by then several things are projected to have happened.

First, in 2105, productivity is projected to have grown such that the overall economy is eight times that in 2005. On average, each of us (or our progeny, really) will be eight times wealthier. At the same time, because productivity in health care has grown more slowly than that for other sectors of the economy, we will spend a much larger share of our wealth on health, 62% of it. This is what freaks people out.

But notice that even though we only have 38% left to spend on other goods and services in 2105, we still have vastly more in absolute terms than we did in 2005. Even though we are spending vastly more on health, we can still afford more of everything else. Why worry?

This brings me to the best part of Chapter 4. In the last few sections of the chapter, Baumol explains why we still have some things to worry about, including:

- The distribution of benefits of productivity growth may be highly skewed. To whom will all that growth in wealth between 2005 and 2105 accrue? If largely to the richest 1%, say, then they will be just fine, but many others will not be. Obviously, under the assumptions that produced the chart above, the wealth exists to make everyone better off in 2105 than 2005, but it is up to us to decide if we wish to ensure it is distributed such that that is the case.

- Too much emphasis on health care cost control, whether by the public or private sectors, could cause unnecessary problems. We ought to spend as much on health care as is allocatively efficient. And we ought to distribute money dedicated to health care in a manner that is productively efficient. Even if you don’t know quite what I mean by those terms (though, follow the links in that case), you can tell that what I’m getting at is that efficiency — using dollars wisely — is what is paramount, not keeping spending below some target that makes us feel good. Too much cost control can hamper quality and, in fact, can be inefficient. Yet, most of our focus on health care is about our level and growth of spending, not on efficient use of the dollars we spend. This is a mistake. It is possible to spend too little on health care, after all.

- To the extent that the government plays a large role in redistributing resources toward health care, Baumol’s projection implies a huge increase in government spending. That implies a huge increase in government revenue (taxes). Do you see a political problem? Go ask Grover Norquist.

- The projection presumes delivery and exploitation of innovation at the pace we’ve seen in recent decades. That could fail to materialize if the incentives that support it weaken. That might happen, for example, if supporting institutions, infrastructure, and government policy do not continue to foster growth in the manner they have. Past performance is no guarantee of future returns.

For all that, Baumol has illustrated that it is at least possible that rapid growth in health care costs need not be viewed as the central problem or even a problem at all. Much more important problems are: fostering productivity growth, promoting efficient use of resources within and across sectors, wrestling with the distribution of gains in wealth and, related, the burden of growing government revenue requirements.

All posts about the book are under the Cost Disease tag.