Andrew Sullivan linked to Roger Ebert’s listing of the documentaries of the year. One caught my eye:

Andrew Sullivan linked to Roger Ebert’s listing of the documentaries of the year. One caught my eye:

“Art of the Steal.”Dr. Albert C. Barnes invented a treatment for VD, and he founded the Barnes Foundation, an art museum in the Philadelphia suburb of Merion. The first paid for the second, so the wages of sin were invested wisely. How important was the Barnes Collection? It included 181 Renoirs, 69 Cezannes, 59 Matisses, 46 Picassos, 16 Modiglianis and seven van Goghs. Barnes collected these works during many trips to Paris at a time when establishment museums considered these artists beneath their attention. One estimate of the collection’s worth is $25 billion.

Barnes hired some Philadelphia lawyers and drew up an iron-clad will, endowing the foundation with funds enabling it to be maintained indefinitely ‘where it is and how it is.” It was his specific requirement that the collection not go anywhere near the Philadelphia Museum of Art. That’s where it is today. He hated that museum. He hated its benefactors, the Annenberg family, founded by a gangster, enriched by the proceeds of TV Guide, and chummy with the Nixon administration. The Annenberg empire published the Philadelphia Inquirer, which consistently and as a matter of policy covered the Barnes Collection story with slanted articles and editorials.

Don Argott’s “The Art of the Steal” is a documentary that reports the hijacking of the Barnes Collection as the Theft of the Century. It was carried out in broad daylight by elected officials and Barnes trustees, all of whom justified it by placing the needs of the vast public above the whims of a dead millionaire. The vultures from Philadelphia were hovering, ready to pounce and fly off with their masterpieces to their nest at the top of the same great stairs Rocky Balboa ran up in “Rocky.” It is not difficult to imagine them at the top, their hands in triumph above their heads.

This makes me very sad.

I grew up literally blocks away from the Barnes House. My mother dragged me on more than one occasion to go see the museum. Later in life, I would bring many visitors there. Yes, the Philadelphia Museum of Art was impressive, but the Barnes collection was insane. And you could walk there from my home.

The museum was a house, except that it was composed of small rooms filled wall-to-wall with incredible art. Paintings were crammed into every available space, above doorways even (see the above picture). There were no ropes keeping you back. Once, when I was younger, I actually reached out and touched the paint on a picture, just because I could. I felt bad afterwards, but there was nothing stopping you. You could get right up close.

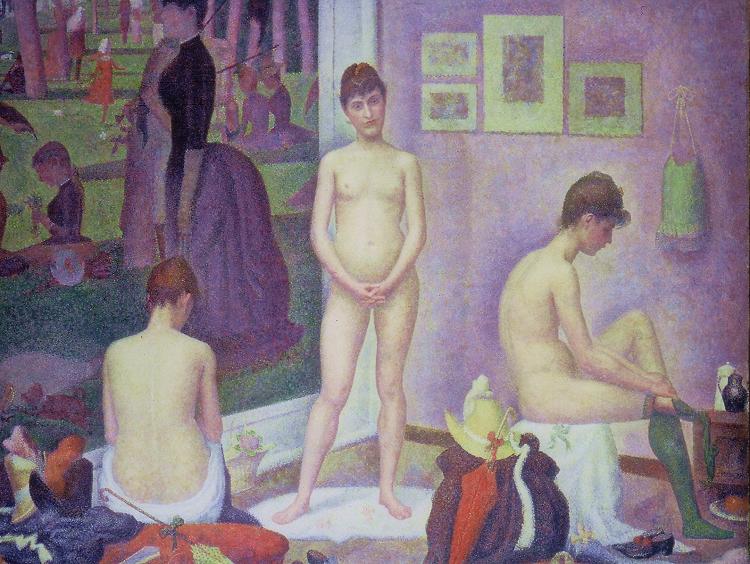

I’m not an art museum kind of guy. But even I could appreciate the Barnes Museum. Just a few days ago, my kids were looking at Seurat’s Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte on some website. I excitedly told them that I used to see this painting all the time:

It was huge. I used to stare at it, amazed at the pointillism. You could get close enough to see at the Barnes Museum. It’s likely you’ve never seen it. Here’s why (emphasis mine):

Following Bathing at Asnieres and La Grande Jatte, Models is the third large picture that Seurat exhibited in public, and the second executed in his new pointillist-or “neo-impressionist”-manner. It was, until now, less famous and popular than the preceding two, only because it has been less looked at and studied, and was almost never reproduced. Nonetheless, one of the artists’ most ambitious works,Models is also among the most important paintings of his career, and one of the richest in interpretive possibilities, as significant for the history of modern painting as Cézanne‘s large Bathers or Picasso’sDemoiselles d’Avignon.

It was less looked at because it was in a tiny museum in Merion, Pennsylvania. But I saw it many, many times.

I told my kids we would go the next time we were in Philadelphia. I assumed, given what I knew about Barnes’ will and fortune, that the museum would still be there. I’m so sad to hear it’s not.