Westyn Branch-Elliman, MD, MMSc is an Assistant Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and a specialist in infectious diseases. She is formerly the Medical Director of Infection Control for the Eastern Colorado VA Healthcare System. She is a clinician investigator at the VA Center for Healthcare Organization and Implementation Research with expertise in epidemiology and implementation science. Her research is focused on measuring the risks and benefits of different infection prevention strategies and on expanding infection control beyond traditional inpatient settings. You can follow her on Twitter: @BranchWestyn

One of the cornerstones of infection control is hand hygiene, but it can be challenging to impart to kids why it is important, and also how to perform hand hygiene most effectively. As a former hospital epidemiologist, promoting compliance with hand hygiene was one of the most important parts of my job: hand hygiene really does save lives.

In my role as Medical Director of Infection Prevention, one of the strategies I found to be the most effective for showing the importance of basic hand hygiene was the “handprint” experiment. The basics are simple: make a handprint on one agar plate, then wash your hands, then make a handprint on another agar plate and compare them. The results of this experiment are usually dramatic—and can lead to a long-lasting memory about the effectiveness of hand hygiene among participants.

Because of the effectiveness of this teaching method, I spent a long time thinking about how to translate it into an at-home or in-school experiment so that kids could also benefit from the visualization of seeing what is living on their hands (at least the bacteria), and how hand hygiene (either with sanitizer or soap and water) impacts bacterial growth, or the “germs living on your hands.” In thinking through how to do this myself, without the back up of a fully functioning microbiology laboratory, the biggest roadblock I encountered was the lack of an incubator—pretty much everything else is readily available on the web. My husband inadvertently solved that problem when he purchased himself a folding proofer for his bread making. One day, we were sitting in our kitchen and he was proofing his bread at a particularly high temperature. While he was programming the machine, I noted that his collapsible proofer could hold a temperature of at least 97 degrees for days at a time and I realized—much to my husband’s horror—I was finally in business.

At the time I designed these teaching experiments (step-by-step instructions can be found here), my kids were in first and third grade, and so I tailored the teaching and the framing to different grade levels. I kept things simple for the younger kids, and just designed a simple pre-/post experiment with hand sanitizer (Option 1 in the step-by-step instructions).

For the older kids, I tried to incorporate some teaching about the scientific method, including developing and testing a hypothesis (Option 2 in the step-by-step instructions). For this version, I split the class in two, with half of the students performing hand hygiene with soap and water, and half performing hand hygiene with hand sanitizer. Then, I asked the kids to make a prediction about which one would work better, and then we tested that prediction (they were surprised by what they found!).

Our Real-World Findings:

Their hypothesis was that soap and water would be superior to hand sanitizer.

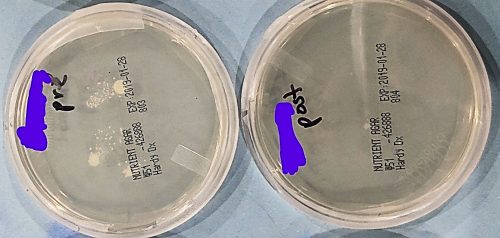

Some pictures of the paired hand sanitizer results:

Note that there are many more little dots (e.g., different bacterial colonies) on the pre-plate than the post-plate. The number of different dots is what you (and the kids) should be looking for to measure efficacy. The post-plate does have one big circle, but that is just one large colony!

This one (also a hand sanitizer example) is particularly good for demonstrating the difference between pre- and post hand hygiene:

Here are a few more examples:

These were some of the examples where you can really see that the hand hygiene worked, and the counters of the fingers on the “pre-plate.”

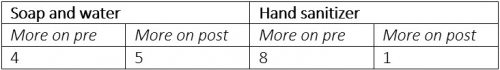

Each kid in the class graded their own plates and we tallied the results as a group. Here are the approximate results:

Being an epidemiologist, I actually calculated a p-value (using a chi-squared calculator to test the significance of the difference between pre and post in soap and water versus hand sanitizer): P= 0.046—statistically significant (which was a surprise—I did not expect it to be with such a small sample)!

How We Interpreted the Results:

We found that our hypothesis was incorrect: in our experiment, hand sanitizer appeared to be superior to soap and water hand washing. This is probably because sanitizer is more user-friendly. We find this pattern in other settings as well, and trials in schools have also suggested that sanitizer is probably better than soap and water. When thinking about infection control strategies, it is always important to think about practical issues and implementation outcomes!

Closing Thoughts:

There are lots of ways to do these experiments—these are a couple of designs that I hope will get you thinking about what you can do! For example, when I did the experiment with my son’s class, I did not include teaching on proper hand washing technique, because I wanted to demonstrate how well soap and water performed in real-world settings, and to compare that performance to the real-world performance of hand sanitizer. Teaching about how to do soap and water could certainly be incorporated into a slightly different design!

Thank you!

Thank you to Ms. Sarah Hammond and her third-grade class for participating in this experiment with me, and to Jasper for permitting me to share his results! I also need to thank my husband, for letting me use his bread proofer (I promise I fully disinfected it afterwards 😊).