“Simply put” is an ongoing series. See the introduction for an explanation of the series and the full list of topics that have been or may be covered. Feel free to suggest other topics in that post.

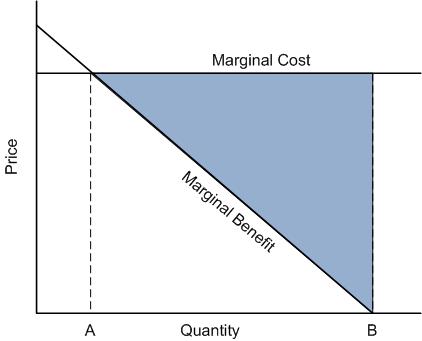

Last week’s “Simply put” post included a discussion of the chart below. It depicts how much health care an insured individual would want to receive, which is the same amount her physician (if properly reimbursed, which I’ll presume holds) would want to provide, quantity B. It also shows how much care an economist would view as efficient (not wasting resources), quantity A.

In an economically perfect market for health care services, quantity A would be purchased. None of the care beyond that would be provided. In a market that maximizes health, on the other hand, perhaps far more care than quantity A would be provided. It turns out that a perfect market for health care or health insurance does not exist. That’s due to various market failures, one of which I’ll explain.

An insurer (public or private) can look at the above chart as well as we can and anticipate that that quantity B of care will be consumed by its customers. That being the case, it will price its policy to account for it. In other words, the insured individuals will have already paid a fair premium that will allow the insurer to purchase quantity B of care without going bankrupt.

What if an individual wants to pay a lower premium, in exchange for less coverage? For example, what if he wants to pay a premium that would correspond to consumption of quantity A of care? Could an insurer write such a policy?

Before I answer that, let me make clear that an insurer can certainly offer a less generous product for a lower premium. For example, an insurer can increase copayments in exchange for a lower premium. Or the insurer can build in a deductible. Covering fewer services or tightening the provider network (i.e., not including the popular hospital in the plan) can also lower the premium. All of these things can push B (the quantity of care the insured individual wants) toward A (the economically efficient quantity), thereby reducing the premium necessary to cover expected utilization.

However, none of this changes one key thing about the graph. The marginal benefit line would still slope downward because to the patient, the next unit of care is less valuable than the last. At some point marginal benefit crosses marginal costs. Now, back to the key question. Can an insurer design a product so that only the (economically efficient) quantity of services corresponding to the intersection of marginal benefit and marginal cost (quantity A) is consumed?

No. Such a policy cannot exist. The reason was discussed in the “Simply put” post on moral hazard, though using different words. Point A is the point at which an individual’s marginal benefit (also called “marginal valuation”) intersects marginal cost. Another way to describe this intersection point is as follows: it’s the point at which the individual is indifferent between receiving the next unit of care or receiving an amount of cash equal to the cost of that next unit of care. That is, it’s the individual’s private determination of the value of that next unit of care.

The insurer does not know the individual’s private valuation. In fact, the individual probably doesn’t know it in advance of the health condition for which he is considering getting care. Quick, how much is a treated sprained ankle worth to you? What about a hernia? An infected appendix? The next visit to your dermatologist? The third visit to your oncologist if you have cancer? I doubt anyone can answer these questions. Moreover, it is impractical or impossible for an insurer to assess the full extent of the health claims that it might seek to cover. Instead, the common practice is to take the stream of health care bills (monetary, not health, claims) as proxies for the health condition itself.

Because the insurer can’t know private valuation or assess health damage-based claims, it cannot offer a policy to bring about use of exactly quantity A of services. Thus, any health insurance policy will lead to some economic inefficiency. In the case depicted above, the insurance leads a level of care that an economist might view as too high, whether it is health improving or not. This is moral hazard. It’s just one type of market failure, which is when a free market cannot be an economically efficient one.* (By the way, this is a market failure that the government cannot solve. If the insurer is a government program, one might just as well call this a government failure.)

There are other market failures pertaining to health care, and moral hazard is just one. Information asymmetry in the doctor-patient relationship is another. There are still more, which have been coved in other posts (here and here).

* There is another economic perspective that views some of this moral hazard as efficient or welfare improving. It brings the economics notion of welfare closer to that of the physician’s. That is, some of the health care use above quantity A is “good” moral hazard. I’ll cover this another time.

Further Reading

David Cutler and Richard Zeckhauser, The Anatomy of Health Insurance, in The Handbook of Health Economics