For some time, I’ve had a beef about research presented at scientific meetings. See, the peer review process for scientific meetings is not the same as that for journals. It’s not nearly as thorough, and those working to do the reviews have many, many more abstracts to review than you would for a journal. Moreover, you only get to see a short abstract, so there’s a lot of information you’re missing in order to judge the quality of the work.

You have to understand how meetings work. Some abstracts are rejected outright. Those that are accepted are presented in one of a number of formats. Sometimes they are posters (in a huge room full of posters), sometimes they are posters where you get to talk for a few minutes, and sometimes they are platform presentations (where you get to do a slideshow). There is an unspoken understanding that those are in order of prestige, from least to most. So platform presentations usually get the most attention.

Again, though, the reasons for how choices are made are unclear. It’s important to remember that the goals of a meeting are different than those of scientists. Organizers want people to come, so they are biased into accepting pieces in general. They are also likely biased into accepting and promoting sensational pieces that will bring media attention to the meeting.

All of this led me to be skeptical of research presented at meetings, as opposed to that in peer-review journals. It especially make me skeptical of the press covering research at meetings.

I bring this up, of course, because of Steve’s post on how church makes you fat. The various media articles aren’t based on a peer-reviewed publication, they are based on a press release for a presentation at a meeting. I don’t think that should carry as much weight.

But let’s not take my word for it, when a study has been done. It was done by me, in fact, when I was a fellow: Does Presentation Format at the Pediatric Academic Societies’ Annual Meeting Predict Subsequent Publication?

OBJECTIVE: The validity of research presented at scientific meetings continues to be a concern. Presentations are chosen on the basis of submitted abstracts, which may not contain sufficient information to assess the validity of the research. The objective of this study was to determine 1) the proportion of abstracts presented at the annual Pediatric Academic Society (PAS) meeting that were ultimately published in peer reviewed journals; 2) whether the presentation format of abstracts at the meeting predicts subsequent full publication; and whether the presentation format was related to 3) the time to full publication or 4) the impact factor of the journal in which research is subsequently published.

METHODS: We assembled a list of all abstracts submitted to the PAS meetings in general pediatrics categories in 1998 and 1999, using both CD-ROM and journal publications. In each year, we chose up to 80 abstracts from each presentation format (“publish only,” “poster,” “poster symposium,” “platform presentation”). We chose either 1) all abstracts in each format or 2) when there were >80 abstracts, a random selection of 80 of them. We assessed each selected abstract for subsequent full publication by searching Medline in March 2003; if published, then we recorded the journal, month, and year of publication. We used logistic and linear regression to determine whether publication, time to publication, and the journal’s impact factor were associated with the abstract’s presentation format.

Here’s the gist. We were able to look at what happened to abstracts submitted to the PAS meeting, which is the biggest pediatrics research meeting around, in 1998 and 1999. We then looked to see if those abstracts were ever published in peer-review journals by March of 2003, four to five years later.

What did we find? First of all, about 87% of abstracts submitted to the meeting were accepted for presentation. That’s really high. Only 13% were rejected. Now, that would be OK if a lot of that work was later published in the peer-reviewed literature. But, 5 years out, around 45% of those abstracts were published.

That means that about one out of every two things you saw or heard at a meeting was never published. Now that would be OK if you were able to guess which work is better. In other words, maybe if the platform presentations were really likely to be published, you could focus on those. But that wasn’t the case either.

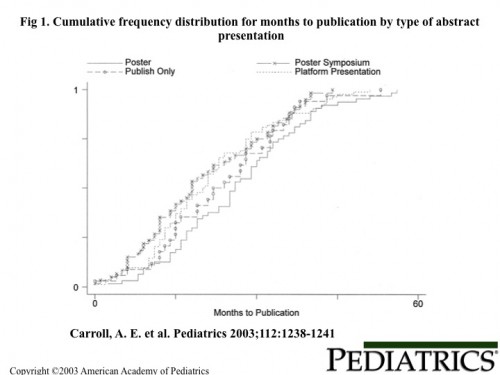

We even went one step further. We looked at time to publication:

On the x-axis is time in months. On the y-axis is the percent of publications that were published. There are the three presentation categories and those that were rejected (called “Publish Only”). There’s really no difference. So what’s the bottom line?

PAS meeting attendees and the press should be cautious when interpreting the presentation format of an abstract as a predictor of either its subsequent publication in a peer reviewed journal, or the impact factor of the journal in which it will appear.

That’s why I don’t trust stories based on meeting presentations. That’s why I’d advise you to be skeptical of them, too. It’s also why I refuse to talk to the media about work I am presenting at meetings. That has annoyed meeting organizers in the past, but based on this study, I think it’s important.