As I noted in my last post, Nicholas Kristof’s column left the impression that welfare dependence is a growing, chronic problem fed by ballooning SSI rolls:

More than 1.2 million children across America — a full 8 percent of all low-income children — are now enrolled in S.S.I. as disabled, at an annual cost of more than $9 billion.

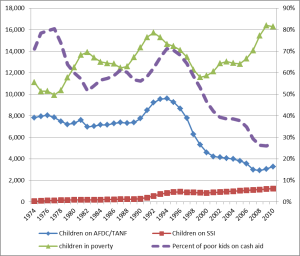

To put this in context, I tracked down some trends in child poverty and welfare receipt over the period 1974-2010. (What I could find 2011 and 2012 seemed quite similar.) Here I included the number of children below age 18 who received either SSI or traditional cash welfare: Until 1996, this was known as Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC). The 1996 welfare reform instituted the more constrained, time-limited program known as Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF).

The ratio of children on cash assistance to children in poverty provides a useful, if imperfect measure of both program generosity and welfare dependence in America. As graphed below, the top green line represents the absolute number of children in poverty—more than 16 million people by 2010. The other two solid lines represent the number of children receiving AFDC/TANF and SSI, respectively, within a given year.

The most interesting curve is the dotted purple one, which is scaled to the right-vertical axis. This is the ratio of children receiving either form of cash assistance to the total population of children under the poverty line. About 28 percent of poor children received federal cash assistance in 2010. That’s less than half of the proportion observed at the passage of welfare reform.

As shown in the bottom curve, absolute SSI receipt is slowly rising. Yet after welfare reform, SSI rolls have held steady for fifteen years at just below eight percent of poor children. Of course, the most dramatic change is in the number and proportion of poor children who receive AFDC/TANF. Both have dropped by more than half in fifteen years. The absolute number of children receiving TANF has sharply declined, even as the absolute number of poor children has markedly increased.

Simply put, cash aid to families with children has failed to keep pace with a deeply punishing recession. As Kristof himself rightly notes,

Our political system has created a particularly robust safety net for the elderly, focused on Social Security and Medicare — because the elderly vote. This safety net has brought down the poverty rate among the elderly from about 35 percent in 1959 to under 9 percent today.

Because kids don’t have a political voice, they have been neglected — and have replaced the elderly as the most impoverished age group in our country.

For many years, SSI-eligible families faced strategic choices regarding whether to apply for SSI or traditional welfare. Families in more generous states were more likely to join AFDC. Families in low-benefit states were more likely to join SSI. The 1996 welfare reform obviously altered this calculation.

This reality creates both the temptation and the real human need to provide economic security and health coverage for families through SSI rather than traditional welfare. Medicaid expansion, CHIP, and health reform lessen the pressure, by providing a non-cash-assistance path to receive essential services. The dilemma remains pressing. Such pressures still provide one reason for the rising absolute number of SSI recipients during a deep recession.

I don’t see much evidence that overall dependence is worsening or that parents gaming the system is the key numerical challenge facing SSI in these difficult economic times. I believe Kristof was led astray by real, powerful, yet unrepresentative impressions of one segment of the SSI population. He is a gifted and humane writer. I hope he returns to this topic, with greater depth and context than he did this week.