Paul Krugman, reacting to Florida’s waiver to direct its Medicaid expansion population to private managed care:

And despite some feeble claims to the contrary, privatizing Medicaid will end up requiring more, not less, government spending, because there’s overwhelming evidence that Medicaid is much cheaper than private insurance. Partly this reflects lower administrative costs, because Medicaid neither advertises nor spends money trying to avoid covering people. But a lot of it reflects the government’s bargaining power, its ability to prevent price gouging by hospitals, drug companies and other parts of the medical-industrial complex.

He didn’t mention Arkansas in the column. The claim/hope for that state is that by permitting newly eligible Medicaid beneficiaries to sign up for private, exchange-based plans, they’ll take advantage of cost-reducing, price-lowering, market competition. I have not yet seen the theory that explains how segmenting the market among multiple private health plans reduces prices. With that stipulated, let’s move on.

First thing’s first. Does Medicaid managed care reduce spending? Mark Duggan and Tamara Hayford asked and answered this question.

[S]hifting Medicaid recipients from fee-for-service into [Medicaid managed care] did not reduce Medicaid spending in the typical state. However, the effects of the shift varied significantly across states as a function of the generosity of the state’s baseline Medicaid provider reimbursement rates. These results are consistent with recent research on managed care among the privately insured, which finds that HMOs and other forms of managed care achieve their savings largely through reduced prices rather than lower quantities. [Emphasis mine.]

Where state Medicaid payments to providers were relatively more generous, managed care organizations had room to maneuver on price and could produce savings. (Aside: the same savings could have been produced by simply lowering state rates.) Where Medicaid payments were relatively low, managed care didn’t do much. On average, according to the Duggan/Hayford study, it doesn’t.

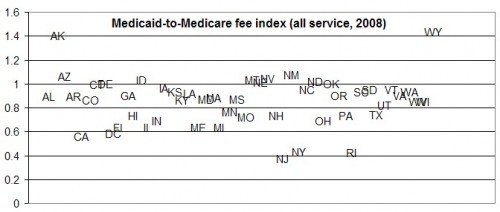

I covered this, and wrote pretty much the paragraph you just read, over a year ago. Then I went a bit further and did something that sheds some light on how much market competition will have to do to bring prices down to what they are under the public program. Exhibit 3 of the 2009 Health Affairs paper by Stephen Zuckerman, Aimee Williams, and Karen Stockley reports state Medicaid rates relative to those of Medicare for all services,* primary care, obstetric care, and other services in 2008. This is handy because Medicare rates are adjusted for variation in underlying cost. Below I’ve graphed the ratios.

There were, in 2008, eleven states with Medicaid physician payments at least as high as Medicare’s (AK, AZ, DE, ID, MT, NE, NV, NM, ND, OK, WY). If you’re looking for a state that has some running room to bring down Medicaid prices through competition or privatization, good candidates are among these. (What’s going on in Alaska and Wyoming?) Note, however, Florida and Arkansas are not among them.

* All services include primary care, obstetrical care, hospital visits, surgery, radiology, psychotherapy, and laboratory tests.