Joseph Antos of the American Enterprise Institute recently highlighted some findings from the Census Bureau. In a report released last week, the Current Population Survey found that 13.4% of Americans were uninsured in 2013. Furthermore, Antos notes:

A day after the two main reports were issued, the CDC quietly placed another table on its website. The new table compares estimates from the NHIS and the CPS for the early months of 2014. It reports the NHIS result that 13.1 percent of the population lacked health insurance when they were interviewed in the January through March time period of 2014. But it also reports the CPS estimate that 13.8 percent were uninsured during the February through April interview period.

Ergo, Antos concludes, the number of uninsured would appear to be higher in the first quarter of 2014 than in 2013, by CPS measures. The story has since been republished on Forbes and picked up by other conservative outlets, including Townhall and the National Center for Public Policy Research. (The AEI post was later taken down, after Antos issued a correction.)

I have a lot of respect for Antos as a conservative commentator on health policy, but his observation glosses over a crucial point. The 2013 statistic is for the number of people who were uninsured for the duration of 2013. That is to say, anyone who had health insurance at any point during 2013 is classified among the 86.6% “insured.” The 2014 measure is the number of people who were uninsured at the time of the interview. We shouldn’t compare longitudinal observations against point-in-time estimates.

If I asked whether you ate breakfast today, you might say no. But if I asked whether you ate breakfast at all this week, the probability that you would say no goes down. I can’t use the fact that you didn’t eat breakfast today to say you were less likely to eat breakfast this week than last week. I need more information.

It’s the same story with these statistics.

Churn is a standard part of our messy, multi-layered health care system. People lose insurance when they lose their jobs. People’s incomes rise and they lose Medicaid eligibility. There’s hope that the ACA will reduce the number and duration of uninsured spells, but the two numbers that Antos points to don’t tell us about whether or not that’s happening.

Those two numbers don’t tell us much at all, because we shouldn’t be comparing them.

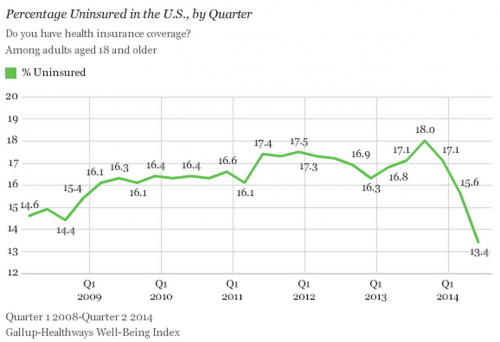

Gallup—which strictly uses point-in-time estimates—has been a demonstrably reliable survey when it comes to measuring the uninsured rate. And there, the news isn’t even remotely ambiguous:

Antos’s broader point, that we don’t know how many previously-uninsured have gained coverage under the ACA, is true. It’s complicated by the fact that Census reports haven’t captured the March enrollment surge yet. But the data so far certainly don’t justify headlines about Obamacare increasing the number of uninsured.

Adrianna (@onceuponA)

Update: on 10/6 Antos wrote another post acknowledging his error.