Austin’s last post is a great one on why raising the Medicare age is a bad idea from fiscal standpoint. But it’s bad for so many other reasons. Here are just a few:

1) It’s likely health will suffer:

The authors found that, relative to those with insurance before age 65, those without insurance prior to Medicare eligibility spent much more money on health care after they became Medicare eligible. In other words, people wait to get care until their Medicare kicks in. This is bad both for health and for the federal government’s bottom line.

Delaying Medicare even longer would likely make this worse. People would forego care longer, health would suffer, and Medicare would pay for the consequences later.

2) It’s a regressive way to “save” money, because poorer people will lose a greater percentage of benefits:

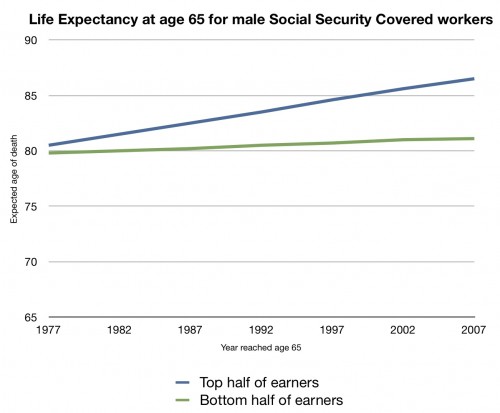

This is the life expectancy of a covered male Social Security worker who reached age 65 in 1977-2007. The blue line is the top 50% of earners; the red line is the bottom 50%. While earners in the top half have seen an increase of their life expectancy at 65 rise about five years over these three decades, the bottom half saw their life expectancy at 65 rise barely a year.

This is what you should think about whenever someone talks about increasing the eligibility age for Medicare or Social Security. Not everyone’s life expectancy is increasing. Those who need the benefits the most would be the ones who stand to lose the biggest percentage of them by raising the eligibility age. Asking them to pay more out-of pocket doesn’t seem like a fair, nor workable, solution.

3) If you raise the retirement age, then a whole bunch of people age 65 and 66 will not be able to buy insurance without the PPACA. Yet there are any number of people trying to get rid of it. How can you bargain away these people’s coverage without some assurance that they will be able to buy insurance?

4) Even if they can buy insurance, it will be ridiculously expensive without the regulations of the PPACA. Chronic conditions are common as people get older, especially in the uninsured population:

Chronic illness is common among persons without insurance. We identified individuals without insurance who had a previous diagnosis of cardiovascular disease (1.3 million), hypertension (5.9 million), diabetes (1.4 million), hypercholesterolemia (4.0 million), active asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (3.5 million), and previous cancer (1.1 million). We estimate that nearly one third of nonelderly U.S. adults without insurance (that is, 11.4 million individuals) had at least 1 chronic condition. These findings counter notions that persons without insurance are a largely healthy population with little need for ongoing medical care.