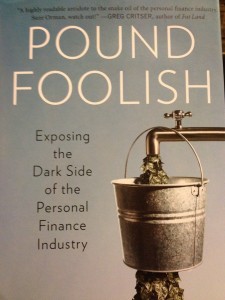

I recently completed a long video interview with Helaine Olen, whose fascinating new book Pound Foolish excoriates the personal finance industry. More on that interview in due course.

I recently completed a long video interview with Helaine Olen, whose fascinating new book Pound Foolish excoriates the personal finance industry. More on that interview in due course.

I’m fascinated by the ways that families respond to financial crises, the way that families save—or don’t save–for retirement, college, or unexpected medical bills. The source of my fascination is clear enough. In 2004, Veronica and I unexpectedly assumed responsibility for her disabled brother Vincent. He faced complex medical and social service challenges. We’ve chronicled this story elsewhere.

His arrival crushed our grand financial plans, too. We never had much money. I had dawdled finishing my dissertation. Then we lived on my assistant professor’s salary while Veronica managed our home and cared for our children while attending graduate school. We had just bought our first home in the summer of 2003. Vincent’s arrival was a scary time, not least from a financial perspective.

Nine years later, he is doing well. Our household economy survived, too. We adjusted our life to fit a simpler single-earner model than we were expecting. No snazzy cars, no fancy vacations or private schools. We own a modest home. We made things work. Every year since 2004, we’ve put aside 25% of our income. I’m here-to-tell-you that spending less, methodically following basic principles of household finance, making sensible, diversified investments really can change your life.

I’m proud of what we accomplished. Yet looking back on these nine years, I realize that many readers couldn’t expect follow the same path. We were helped at so many points by simple luck, the security provided by an upper-middle-class income, and the generosity of social insurance programs that quietly protect us without our even noticing.

Luck

We benefitted from lucky accidents of timing. We benefitted even more from things that didn’t happen—or at least didn’t happen at the worst moments. Our family crisis hit right after I was awarded tenure. Had things happened a few years before, Vincent’s arrival would have derailed my career the same way it derailed Veronica’s. There were other things, too. My mother-in-law left a modest home outside Oneonta, NY. It sat unsold, a financial albatross, for a year. Fortunately, we managed to sell it just before the market crashed.

Oh yeah. We didn’t divorce. That’s not cause for complacency or self-righteousness, either. Loving marriages easily crack in a crisis, or shortly thereafter. Maybe one partner loses a job and spouses disagree about where to go next. Maybe your marriage doesn’t survive general stress, disappointment, or changes in family roles. Divorce is expensive. It can also make people crazy right when they face big financial and life decisions.

A good, secure job

When I noted our good luck, you might have expected the obligatory: “And no one else got sick.” Actually, Veronica did get sick. She landed in a cardiac ICU with a scary heart infection several years ago. That brought more than $50,000 in medical bills. Fortunately, our insurance covered almost everything with little hassle. The full cost (to the university and to us) of that nice tax-subsidized family policy: $17,000/yr. Tenured full professors can afford that kind of insurance. Most Americans can’t.

My job has helped in other ways. Veronica could focus on caring for her brother, knowing that my paycheck was secure. Historically low interest rates allowed us to cheaply refinance our mortgage, twice. Our less-affluent, underwater neighbors can’t do that.

We also availed ourselves of various tax-advantaged savings vehicles. We max out our 401(k) account. We also rely on an alphabet soup of other tax-favored options: SEP- and Roth IRAs, 529s, and ESAs. I now have a 457(b)–whatever that is. All of these accounts have blossomed during the worst-socialist-ever-Obama stock market boom. Since Inauguration Day 2009, our untaxed capital gains on our daughters’ college accounts amount to one full year of college tuition each.

These active-savings incentives are hard to justify in policy terms. They soak up billions in tax expenditures, which mainly benefit affluent people. There is surprisingly little evidence that these increase overall national savings. Hey, this is America. I’ll grab these opportunities.

Don’t forget public insurance

We also benefitted from Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. As a “disabled adult child,” Vincent receives an inflation-protected monthly Social Security benefit of about $1,100. Those checks were a Godsend in his first months with us, when he required supports ranging from medical help to hospital parking fees to a sturdy recliner that could support his 340-pound frame.

Much ink is spilled regarding Medicaid’s shortcomings. A lot of the pointed criticism comes from conservatives opposed to universal coverage. We’ve seen quite enough of Medicaid’s gaps and shortcomings. American social insurance isn’t always smooth or pretty. We’re still so grateful for the services Vincent receives. The steady stream of five-figure bills gets paid. Essential services are provided. Without this support, Vincent’s care would have wiped us out. He might well have ended up in the back ward of some institution someplace.

The necessity and the limitations of smart personal finance

I’ve noted these personal financial realities for reasons that come back to Helaine Olen’s book. My family has saved well. You should try to do the same. But don’t expect people can replicate our experience across the income and education distribution. It’s easy to blame people for their poor choices, poor job skills, or lack of investment acumen. And when you’ve gotten past terrible financial challenges, as we hope that we have, it’s easy to be a bit self-righteous, too.

So much willful naiveté pervades the world of personal finance. So many commentators and researchers express an ultimately misguided hope that effective financial management by individuals will accomplish more than it actually can.

For reasons Olen relates, millions of people won’t save for their retirement. They just won’t. Yeah, these failures partly reflect mistakes, impatience, and naiveté. People will under-contribute to (and screw up) their 401(k) accounts. Seniors, desperately afraid of outliving their savings, will fall for rip-off variable annuities sold over a free dinner in the local steakhouse. People will follow deeply dubious advice from self-interested financial advisors and television personal finance gurus.

I’m all-in for policies that reduce the stupidity, that promote financial literacy and encourage smart choices, policies that give people a helpful nudge to save along the way. This won’t be enough. People’s failure to save goes beyond individual miscalculation. It reflects punishing realities of our national economy. People get sick and lose jobs. The bottom half of the income distribution has been hammered by low wage growth since the 1970s.

Until these economic realities change, personal finance will be a mug’s game for millions of families. And until these economic realities change, people like me should pay higher taxes to support stronger insurance structures that protect people in illness, disability, and retirement.

That’s the right thing to do. It’s the smart thing to do, too. I’m-here-to-tell-you: You never know when your own family might need the help.