Senior officials reported that some 1.5 million people might be eligible for the latest administrative tweak to the Affordable Care Act, an extension of the “like it/keep it” fix that would permit individuals to maintain plans that don’t meet new coverage requirements through October 2017. The move has already been roundly criticized, but I’m inclined to believe the substantive policy impact will be small.

The thing about the individual market is that it’s volatile. The Kaiser Family Foundation found that about a third of those enrolled in nongroup plans exit within six months. Fewer than half remain after two years. This coverage is transitory for many, a bridge between employer-sponsored plans or other forms of insurance. Since the “fix” only applies to people maintaining these plans, the population eligible for the extension will dwindle over time.

There’s a fear that individuals who cling to old, less generous plans are healthier than those who already jumped to the exchanges. That might be true, but it also probably doesn’t matter much. CBO estimates that the exchange population will swell to 22 million by 2016 as people become more aware of coverage options and the penalty becomes more severe. The specter of adverse selection fades pretty fast when you set 1.5 million—a number that will erode over the life of the administrative fix—in that context.

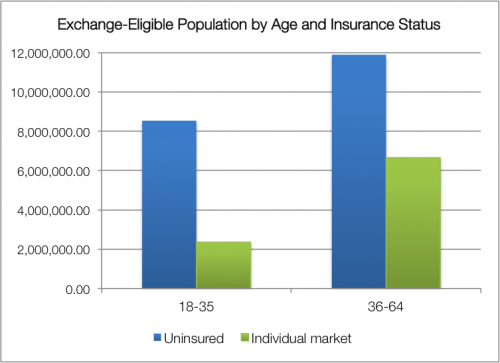

When we talk about exchange enrollment and balanced risk pools, we care about those without coverage, too. I ran some Census data to explore this point last fall. Take a look at the prospective exchange population: about two-thirds are uninsured, not coming from the individual market—and the uninsured skew younger. Considering the enrollment growth anticipated by the CBO, this matters.

It’s true that the uninsured are, on average, less wealthy and may be less healthy. But the individual market also skews older, with individuals over 35 more likely to enroll than their younger counterparts. The young-old distribution of the uninsured is a little more equal […] It’s a tricky business to try predicting consumer behavior—income and subsidy availability will matter, too—but it’s worth noting that people with nongroup plans only makes up about a third of the prospective exchange population; the impact of losing some from the individual market may be overstated.

Furthermore, not all states opted into the administrative fix. Back in November, HHS decided to let state insurance commissioners decide whether or not to take advantage of like it/keep it at all. About twenty decided against it. If the fix proves disruptive or destabilizing in the first year, states can discontinue the practice. And just because a state opts in doesn’t mean an insurer is obligated to continue offering old plans; ultimately, we’re talking about business decisions.

I don’t think the extension will matter profoundly, but I’m not trying to defend its optics, either. The politics feel nakedly transparent, and there are some lingering legal questions I might call “uncomfortable”. More to the point, issuing delays that will burden insurers and confuse consumers three weeks before the end of open enrollment? There are wiser ways to handle policy.

UPDATE: See Kevin Drum’s follow-up commentary here. He cites findings in Health Affairs that have the proportion of individuals maintaining nongroup coverage for two years down to 17%.

Adrianna (@onceuponA)