One of the simplest and yet most difficult health services problems involves the barriers to the delivery of specialized medical care to people living in remote areas.

Consider the province of Ontario. It’s a big place: over 1 million km2, compare this to the unimpressive 700 thousand km2 of Texas. Most Ontarians live in the southeast, near the Great Lakes or the St. Lawrence River. But some live in, for example, Fort Severn, near the Manitoba border on Hudson’s Bay, where there is a First Nations reserve (what an American would call an ‘Indian Reservation’). Fort Severn is 1478 kms from Toronto as a very rugged crow might fly. There are no roads connecting Fort Severn to any other community.

It’s difficult to deliver specialized medical services to people in remote areas. You can fly people to the southern cities for surgeries. But that’s a poor option for chronically ill people who need regular care.

Unfortunately, some chronic illnesses are concentrated in remote places. In Canada, there are clusters of mental health and substance abuse problems in the north, including many First Nations communities. Health Canada reports that suicide rates among First Nations youths are an astonishing five to six times higher than among the general population. Rates among the Inuit youths (the indigenous people of the Arctic), are even higher. Pikangikum (Ontario) is believed to be the community with the highest suicide rate in the world. Pikangicum is 1416 km from Toronto and, again, effectively unreachable except by air.

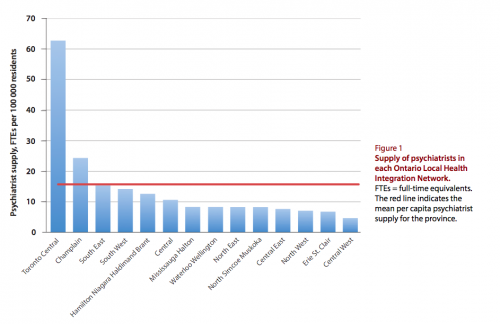

Unfortunately (again), Ontario’s psychiatrists are highly concentrated in the southeastern cities. The Figure below, from Paul Kurdyak and his colleagues, shows the numbers of psychiatrists per 100,000 residents in each of Ontario’s Local Health Integration Networks (LHINs, a scheme for dividing the province into health catchment areas). The towering bar on the left is Toronto. The next bar to the right is Ottawa.* Mental health professionals are the kind of people who prefer to live in the metropolis, and have the means to do it.

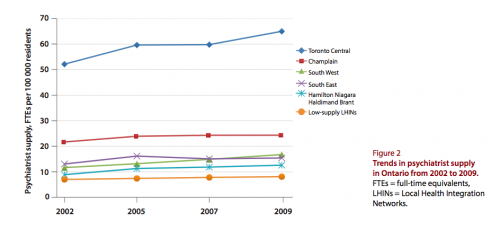

Ontario has tried to address the problem of lack of access to psychiatrists by hiring more of them. But as you can see in the next Figure, this just resulted in an increasing concentration of them in Toronto.

As more psychiatrists started practicing in Toronto, the number of patients seen by each psychiatrist in that LHIN declined.

as the supply of psychiatrists increased, outpatient panel size for full-time psychiatrists decreased, with Toronto psychiatrists having 58% smaller outpatient panels and seeing 57% fewer new outpatients relative to LHINs with the lowest psychiatrist supply. Similar patterns were found for inpatient practice. Moreover, as supply increased, annual outpatient visit frequency increased: the average visit frequency was 7 visits per outpatient for Toronto psychiatrists and 3.9 visits per outpatient in low-supply LHINs. One-quarter of Toronto psychiatrists and 2% of psychiatrists in the lowest-supply LHINs saw their outpatients more than 16 times per year. Of full-time psychiatrists in Toronto, 10% saw fewer than 40 unique patients and 40% saw fewer than 100 unique patients annually; the corresponding proportions were 4% and 10%, respectively, in the lowest-supply LHINs.

An increased number of visits per patient might represent better care for those patients. But it is unlikely to be optimal for the population mental health of Ontarians, nor does it help address the acute disparities in mental health and access to mental health services.

Poor access to specialty care is a central problem in global health. There are billions of people who have minimal access to specialty care and millions who therefore die annually as a result of treatable conditions.

But the Ontario example suggests that however obvious it seems, simply increasing the supply of specialists is unlikely to fix the access problem. There are better approaches, which I hope to address in a later post.

*Where, I must disclose, I live. As a mental health professional, I am part of the problem depicted by the Figure.