A recent issue of the New England Journal of Medicine included a concise exploration by Robert Kocher and Nikhil Sahni of an ongoing trend: increasingly hospitals are employing physicians. (The paper is ungated.) What was once more commonly viewed as two types of enterprises, hospitals and physician groups, is now, more often than not, more correctly viewed as one, hospitals and their employed physicians.

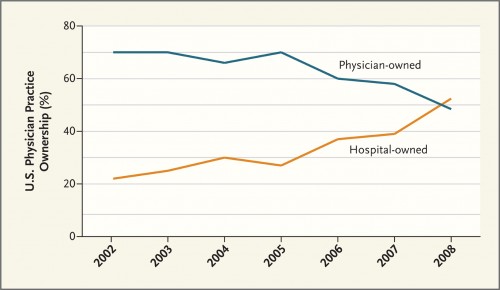

What’s going on? Why is this happening? What does it mean? I’ll answer those questions in turn. Clearly from the graph above (from the paper), the movement toward hospital-ownership of physician practices and away from physician-ownership has been going on for at least a decade. A similar phenomenon occurred in the 1990s, but it was followed by a disintegration. One can’t blame the latest trend on the anticipation of ACOs. Nevertheless, that the health reform law will provide incentives to create ACOs, encourages health care organizations to integrate across provider types. It can only accelerate the trend depicted in the figure above. As the article’s authors put it,

After the current cycle of physician-practice acquisitions, it will be harder to revert to private practice if relationships sour, since new payment structures and care models will make it increasingly difficult for traditional private practices to remain profitable.

Interestingly, according to the authors, hospitals lose between $150,000 and $250,000 per physician per year in the first three years of employing a physician. There has got to be some compelling, longer-term rationale for integration in order to accept that level of loss. What could that rationale be? Kocher and Sahni suggest that hospitals are trying to position themselves to capture more referrals. Hospitals, therefore, are hiring primary care physicians out of

fear [that] physicians [will] becom[e] competitors by aggregating into larger integrated groups that direct referrals and utilization to their own advantage. Hospital-employed PCPs generally direct patients to their own hospitals and specialists affiliated with them. In addition, by employing physicians, hospitals retain maximum flexibility in the market, should health plans change their reimbursement structures to require providers to bear risk and manage population health.

Meanwhile, young doctors may seek hospital employment due to lifestyle factors, like a “better work–life balance, […] flexibility and administrative simplicity provided by hospital employment.”

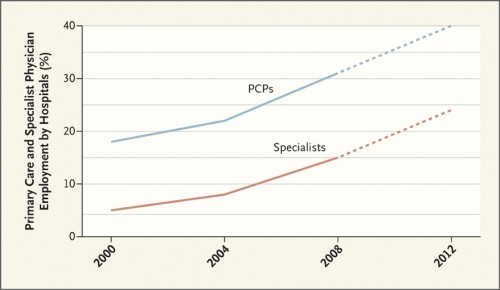

Interestingly, the authors note that different payment schemes suggest different hospital hiring strategies. On the one hand, if fee-for-service payment systems continue, hiring more specialists is advantageous as it will allow the hospital to capture a greater care volume and revenue across a wider range of specialty services. It will also increase a hospital’s power to negotiate higher prices.

On the other hand, if ACO-like models predominate, having a large outpatient network at one’s disposal would facilitate the shifting of patients from high- to low-cost settings. A hospital that succeeds in doing this would be able to retain more of the bundled payment or receive higher cost-based incentive bonuses. Having an army of specialists on staff eager to perform more services would not be as consistent with this strategy. It, therefore, favors the hiring of primary care physicians (PCPs).

So far, hospitals are hedging. They’re hiring more of both specialists and PCPs, as shown in the figure below.

Kocher and Sahni end with a note of optimism.

In the long run, any pricing distortions derived from market power and friction associated with changing the role and behaviors of physicians are likely to dissipate and be outweighed by improved productivity, outcomes, and patient experiences, and more efficient health care markets may translate into lower prices over time.

That is the best possible spin on integration, but it is not a guaranteed outcome and far from likely in the near term. One thing I’ve learned in paying close attention to the history of health care in America is that thing rarely evolve according to plan.