One of my regular complaints about the blunt instrument of cost-sharing is that it works great for healthy people, but terribly for sick people. For healthy people, it makes sense – you want healthy people to avoid care they don’t need and so economically incentivizing them not to get it is a great idea. But sick people – people with chronic conditions – we want them to get care. Therefore, economically incentivizing them not to get it is a bad idea.

This month, in Health Affairs, a paper* addresses just that:

High-deductible health plans—typically with deductibles of at least $1,000 per individual and $2,000 per family—require greater enrollee cost sharing than traditional plans. But they also may provide more affordable premiums and may be the lowest-cost, or only, coverage option for many families with members who are chronically ill. We surveyed families with chronic conditions in high-deductible plans and families in traditional plans to compare health care–related financial burden—such as experiencing difficulty paying medical or basic bills or having to set up payment plans.

Before we get into the weeds, here’s the difference between high-deductible and traditional plans:

For this study we defined high-deductible health plans as plans with annual family deductibles of at least $1,000, with or without a savings option. The Harvard Pilgrim high-deductible plans studied had family deductibles up to $6,000 per year. Services subject to the deductible included emergency department visits, diagnostic tests, hospitalizations, and therapeutic procedures such as physical therapy.

In most plans, office visits were subject to a $20 copayment and were excluded from the deductible. Prescription drugs were also exempt from the deductible and subject to copayments. In high-deductible plans eligible for health savings accounts, nonpreventive office visits and prescription drugs were subject to the deductible. Preventive services were covered at no cost.

The maximum amount enrollees were required to pay out of pocket for health care ranged from $4,000 to $10,000. Health reimbursement arrangements or health savings accounts were available but not offered by all employers.

The traditional plan group consisted of plans that did not have a deductible. These plans had office visit copayments ranging from $5 to $25, emergency department visit copayments ranging from $0 to $100, full coverage for preventive care and diagnostic tests, and limited cost sharing for hospitalizations. Most had out-of-pocket maximums of $4,000.

So high-deductible plans require spending at least $1000 (and up to $6000) out of pocket to get tests, hospitalizations, ER visits, and more. In addition, there were co-pays for other things. This isn’t uncommon. The whole point is to try and make you “feel it” more when you get care, so that you get less of it. The traditional plans, on the other hand, had no deductible. Cost-sharing existed, but out of pocket-spending was less, and was capped at a lower amount.

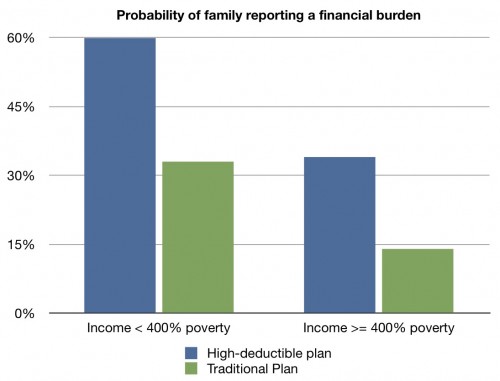

The purpose of the study was to compare the financial burden of people with chronic conditions in the two types of plans. What did they find? (I made the following chart from their data.)

Even after adjusting for other factors, a family with a member with a chronic condition was about twice as likely to report a financial burden if they were in a high-deductible plan than in a traditional plan. This was true whether the family was well-off or making less than 400% of the poverty line. For families making less than 400% of the poverty line (many of whom we would not consider poor), 60% of those in high-deductible plans reported having a financial burden. More than half of those families reported that out-of-pocket health care expenses were more than 3% of their income.

I’m not denying that the economic incentives of cost-sharing work. I’m not denying that high-deductible plans are cheaper than traditional plans, and so would allow more people with limited means to buy insurance. As I noted last week, however, there is a lot of fuzziness in what we all think of when we define insurance.

Me? I define insurance to mean the ability to get needed care without fear of financial hardship or bankruptcy. High deductible plans allow many people to say they have insurance, but if illness still causes you financial hardship, or leads to bankruptcy, I believe you are underinsured.

The disagreement here is that health insurance is the same as any other insurance. If you are a bad driver, for instance, your insurance costs more, or you accept a plan with a very high-deductible. Some of you think the same argument should apply to health care. But as one of the millions who has a chronic disease which is not my fault, I don’t agree. Moreover, unlike some people who could learn to become better drivers, I cannot lose my chronic illness or medical history.

So I’ll say it once again. I think that shifting more and more people to high-deductible plans as a blanket solution to our health care system’s ails is a bad idea. It will result in much cheaper rates for healthy people and may seem like a great idea initially. But it will likely cause harm to sick people and people with chronic conditions, the very people I’d argue the health care system is for. There’s likely a place in the health care system for the use of cost-sharing as an economic incentive, but I don’t think it should be the overall philosophy.

*Full disclosure – one of the authors is a close, personal friend of mine. I won’t embarrass the person by saying which one, but you should all know the conflict exists.