The following is a guest post by Stacey McMorrow (@staceymcmorrow), Principal Research Associate, Health Policy Center, Urban Institute; Genevieve M. Kenney (@kenneygm), Co-Director and Senior Fellow, Health Policy Center, Urban Institute; Emily M. Johnston (@_EMJohnston), Research Associate, Health Policy Center, Urban Institute; and Jennifer Haley, Research Associate, Health Policy Center, Urban Institute. This work was supported by the David and Lucile Packard Foundation.

Having a baby is physically and mentally taxing. Losing access to health insurance in the months that follow only adds to this stress. Unfortunately, this situation is all too common, especially for women who rely on Medicaid during their pregnancies.

According to a Health Affairs blog, although only about 3 percent of women who delivered babies in 41 states from 2015 to 2017 were uninsured at the time of delivery, approximately 13 percent were uninsured 2-6 months later. This increase in uninsurance corresponds with a decline in Medicaid—about 42 percent of women were covered by Medicaid for delivery but only 27 percent had Medicaid coverage postpartum.

Since the early 1990s, states have been required to offer Medicaid coverage to pregnant women with incomes up to 133 percent of poverty and, in 2017, the median income eligibility threshold for pregnancy-related coverage through Medicaid was about twice the poverty level. This pregnancy-related Medicaid coverage expires about two months after delivery, however, at which time mothers are subject to their states’ parental Medicaid eligibility thresholds.

In the 32 states that expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) by 2017, women with incomes below 138 percent of poverty would retain parental eligibility after delivery, but those with higher incomes who qualified for pregnancy-related coverage would lose their Medicaid coverage postpartum. An even higher share of women would lose Medicaid postpartum in the 19 states that did not adopt the ACA Medicaid expansion. There, the median parental eligibility threshold was just 44 percent of poverty in 2017—well below the median level for pregnant women.

Postpartum uninsurance has been identified as a potential contributor to a growing maternal morbidity and mortality crisis, and there were several state-specific efforts in 2019 to extend Medicaid coverage beyond 60 days postpartum. In addition, the Helping Medicaid Offer Maternity Services (or Helping MOMS) Act was voted out of the House Energy and Commerce committee in November 2019 and would provide every state the option to extend Medicaid coverage for postpartum women for a full year.

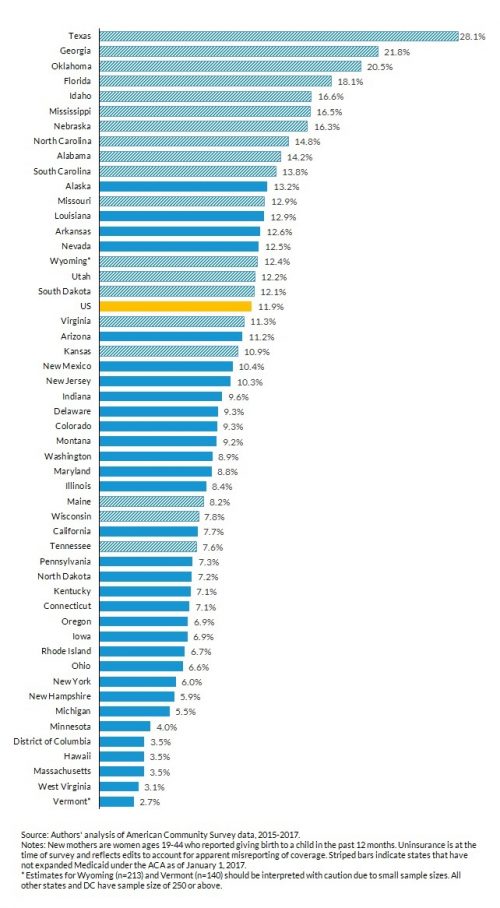

To consider the potential benefits of a postpartum Medicaid eligibility extension, we used American Community Survey (ACS) data to examine insurance coverage among a nationally representative sample of women ages 19-44 who reported giving birth in the past year. Overall, we found that about 12 percent of new mothers were uninsured from 2015-17, with wide variation across states (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Percent Uninsured among New Mothers, by State, 2015-2017.

Uninsured rates among new mothers ranged from above 20 percent in Oklahoma, Georgia and Texas to below 4 percent in DC, Hawaii, Massachusetts, West Virginia and Vermont. None of the ten states with the highest uninsured rates among new mothers had expanded Medicaid under the ACA, while all 17 states with uninsured rates less than 7.5 percent had done so by 2017.

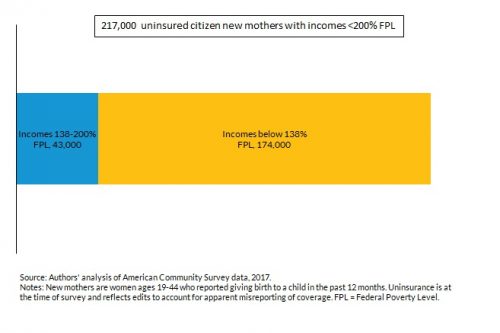

Nationwide, approximately 451,000 new mothers were uninsured in 2017, and about 217,000 were US citizens with incomes below 200 percent of poverty (Figure 2). These women would be most likely to benefit from a postpartum eligibility extension, having incomes that would qualify for pregnancy-related Medicaid in most states. The other 234,000 uninsured new mothers who were not US citizens and/or had incomes above 200 percent of poverty are less likely to qualify for pregnancy-related Medicaid because of restrictions related to income or their residency status and years in the US.

Figure 2. Estimated number of low-income uninsured citizen new mothers, 2017.

Of the 217,000 low-income uninsured citizen new mothers, about 20 percent (43,000) had incomes between 138 and 200 percent of poverty. These mothers are unlikely to be eligible for parental Medicaid due to their income, and although some may qualify for subsidized Marketplace coverage, they may not be aware of it or may not be able to afford the premiums and out-of-pocket cost-sharing requirements.

Extending pregnancy-related Medicaid coverage up to one year postpartum would provide a more affordable option for these new mothers. This coverage would be temporary, but it could increase access to care during a critical period following delivery when pregnancy-related health complications often occur.

The remaining 80 percent (174,000) of low-income uninsured citizen new mothers had incomes below 138 percent of poverty. For those in nonexpansion states (70% of the 174,000), a postpartum extension, while temporary, would increase new mothers’ ability to access needed health care during the postpartum period.

For those in Medicaid expansion states (30% of the 174,000), most are likely already eligible for Medicaid after their pregnancy-related Medicaid coverage expires. Uninsurance in this group suggests that not all women are experiencing smooth transitions from pregnancy-related coverage to parental Medicaid coverage.

Extending postpartum Medicaid coverage has the potential to help at least 200,000 low-income uninsured citizen new mothers gain coverage. Others with higher incomes and some noncitizen mothers could also benefit, especially in states that currently provide more generous pregnancy-related coverage through Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program. A postpartum extension would allow new mothers to maintain continuity of care in the year following delivery, access critical health services as they recover from pregnancy and delivery, and potentially transition to other sources of coverage on a more flexible timeline.

A postpartum Medicaid extension would only benefit women in the first year after pregnancy, however, leaving other low-income mothers and fathers at risk of uninsurance, particularly in nonexpansion states. Evidence from the ACA Medicaid expansion suggests that a more comprehensive expansion has the potential to increase coverage, access to care, and financial well-being among both new mothers and other parents.

Even with a temporary extension or a comprehensive expansion, more outreach and enrollment efforts are likely needed to ensure that new mothers who are eligible for Medicaid or subsidized Marketplace coverage get enrolled before their pregnancy-related coverage expires.