The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2019, The New York Times Company)

There’s a logic to out-of-pocket medical payments. They’re supposed to make patients think twice before spending money on unnecessary health care.

When it comes to drugs, however, they’re often preventing people from getting necessary care.

A recent data brief from the National Center for Health Statistics said about a quarter of adults who had diagnosed diabetes asked their physician if there was a lower-cost medication they could try, even if things were working for them.

Thirteen percent of them had not taken their medication as prescribed because of the cost.

Some of these patients were uninsured. More than a third of such patients had not taken their medication as prescribed because of the cost; that was also the case for about 18 percent of those with Medicaid. What might be surprising, though, is that 14 percent of patients with private insurance went without their medication as well.

A study in Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice last year examined data on cost-related skipping of diabetes medication. They found that more than 16 percent of those with diabetes engaged in this practice. Those who used insulin and those who earned less than $50,000 per year were more likely to do so.

Such behavior isn’t localized to diabetes. Multiple studies have shown that when more cost sharing is involved, patients are less likely to stick to drug therapy. This is true when considering birth control, as well as the treatment of high cholesterol, high blood pressure and other chronic care medications.

It’s even true in cancer.

Before the introduction of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (T.K.I.s), patients with chronic myeloid leukemia could expect to live five to six years after diagnosis. These medications, taken orally every day, can lead to full life spans. They are costly, however, and need to be taken for the rest of a patient’s life.

In 2013, Stacie Dusetzina, an associate professor of health policy at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, and colleagues published a study in which they looked at health plan claims from 2002 through 2011. They wanted to examine adults who had chronic myelogenous leukemia and who initiated therapy with imatinib, the first tyrosine kinase inhibitor. These were all patients with private insurance.

The researchers found that patients with relatively higher monthly co-payments ($53) were more likely to discontinue therapy within six months than those with lower co-payments (17 percent versus 10 percent).

Stopping the therapy can lead to recurrence, even death. “One of the biggest concerns about cutting back on medications due to cost is that some medications only work well if you take them exactly as prescribed,” Dr. Dusetzina said. “Even worse than that, in some cases if you take only part of what you are prescribed, your disease can change so the drugs no longer work for you. This can happen in the type of cancer that imatinib and other T.K.I.s are used to treat.”

More than 8 percent of all Americans between 18 and 64 have not taken medication as prescribed because of the cost to them. Even 6 percent of those with private insurance haven’t taken recommended drugs because of what they still had to pay.

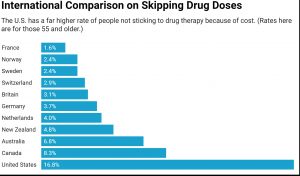

This is mainly an American problem. A study published two years ago in BMJ Open compared rates of cost-related skipping of drugs among people 55 and older in 11 high-income countries. Most countries had a prevalence lower than 4 percent. The second-to-highest rate was in Canada, at 8 percent. (This was still less than half the prevalence we see in the United States, at almost 17 percent.)

Canada’s single-payer system is sometimes held up as the preferred “other” model to the American status quo. But its drug coverage isn’t so good compared with the rest of the world. Pharmaceutical coverage is not part of Canada’s Medicare system, and differs from province to province. Still, Canadians do better than Americans.

A study in Clinical Therapeutics about a decade ago specifically compared the rates of cost-related nonadherence in the United States and Canada. Uninsured Americans were seven times as likely to skip doses of medication. Those with public or private insurance were more than twice as likely.

Insurance isn’t enough, it seems clear. In 2015, researchers published a study in the Journal of General Internal Medicine that looked at medication adherence and cost-saving strategies of those who have Medicare. About 40 percent of this population took actions to try to cut their costs. Some are relatively innocuous — asking for free samples, for example. But more than 3 percent of those surveyed admitted to buying their drugs from another country, and almost 3 percent bought drugs over the internet.

Almost 13 percent split their pills or took less than the prescribed amount to make medications last longer. But this is not how medications work. With many drugs, like imatinib, it can even make things worse.

Most of the discussions around the cost of drugs focus on the extreme amounts that the system will have to pay drug companies so that people can get them. Relatively few discussions focus on the relatively smaller amounts we still require of patients to receive them. These smaller amounts are still a major barrier to care.

“Unfortunately, we — as a society — don’t do a good job of making it easier to afford care with clear benefit and harder to pay for care that is more questionable,” Dr. Dusetzina said. “If we weighed those trade-offs more, I think we could get to a place where drugs that worked were affordable for patients, and companies were paid for their very high-value products.”

Cost sharing is supposed to lower spending without sacrificing quality. It was not meant to prevent patients who need drugs from receiving them.