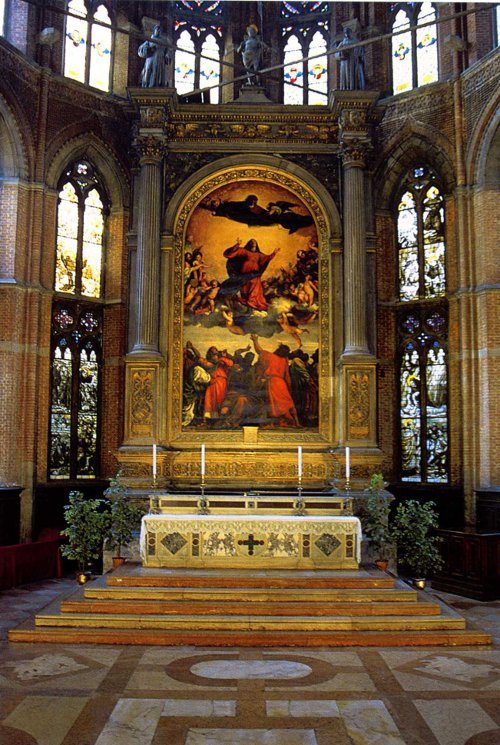

My wife and I were in Venice recently. You may have heard about the city’s crowds and the smell of stagnant water. Visit in January when it’s cold. You could find yourself alone in a church, in front of the most beautiful painting you have ever seen.

Unfortunately, AirCanada lost our luggage for several days. We hadn’t thought to put our power adapters in our carryon bags, so we couldn’t charge our devices.

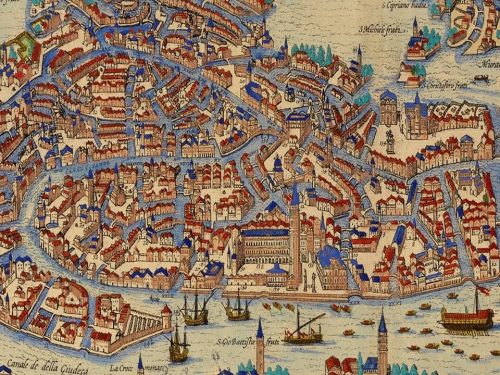

Letting our devices die was wonderful. We had no email, social media, podcasts, recorded books, or GPS-powered maps. Exploring a city without Google maps is interesting. Venice is a random graph, traversable only by foot or by boat. Piazzas are connected by canals, alleys, bridges, and little tunnels. There are no right angles. After a few days, however, we could find our way around. Perhaps it was because we were looking at the city instead of our phones.

The best thing was what happened to my writing. I rose early for a couple of hours each morning, working in black ink on graph paper. Outlines for several papers flowed quickly onto the pages. In part, I was stimulated by the setting. But I also benefited from what Cal Newport calls digital minimalism. Newport argues that disconnecting from the internet helps you concentrate.

[Y]ou should avoid wasting your limited time and attention on low-value online activities, and instead focus on the much smaller number of activities that return the most value for your life. This is a basic 80/20 analysis: doing less, but focusing on higher quality, can generate more total value.

The reason is that

You have a finite amount of attention to expend each day. If aimed carefully, your attention can bring you great meaning and satisfaction. At the same time, however, hundreds of billions of dollars have been invested into companies whose sole purpose is to hijack as much of your attention as possible and push it toward targets optimized to create value for a small number of people in Northern California.

Cut off from the internet, my brain was not processing research messages, reviews for the hospital ethics committee, diverse tasks for the journal I help edit, or Twitter’s perpetual turmoil. Sheltered from this turbulence, I had more capacity to see and lay out extended arguments.

So now I’m home in Canada with a commitment to shelter more time from the internet. But how much? Newport acknowledges that few of us can or should completely disconnect. He is an applied mathematician and solitude is an ideal work environment for proving theorems. But I can’t become a digital hermit. Running a lab, doing administrative service, and trying to drive clinical practice change are all practices that require digital media.

However, those activities don’t account for all the time I spend online. Newport asks us to reflect on what will “return the most value for your life” and to focus on that. So I’ll start by asking what was the point of the blogging and — God help me — tweeting?

And there was a point. Through the health policy blogosphere, I have made friendships with people whom I wouldn’t have encountered otherwise in disciplines I barely knew. I’ve learned a lot and it has improved everything I’ve done in the last decade.

Moreover, I claim that TIE itself has, in a small way, changed the world by showing researchers and journalists how to disseminate research. Our goal has been to make health services research available to clinicians, health organization leaders, policymakers, other academics, and intelligent laypeople through writing that is, as Austin put it, “fast, accessible, knowledgeable, relevant, [and] credible.” TIE has informed many of the last decade’s key health policy debates. At the Times, Aaron and Austin are now bringing the style they honed here to millions of readers.

These days, however, the suggestion that science could influence US health policy seems like a joke in questionable taste. The government can’t keep the National Parks open, and it’s going to tackle health care? In 2017, a bill to repeal and replace the ACA was voted on the same day it was introduced and came within one Senate vote of passing. There is a temptation to withdraw from the public sphere, focus on research, or maybe just enjoy life.

That choice seems wrong. I recall how the Hungarian Marxist literary critic György Lukács scorned the detached, elitist academic leftism of Theodor Adorno and other Frankfurt Schule philosophers.

A considerable part of the leading German intelligentsia, including Adorno, have taken up residence in the ‘Grand Hotel Abyss’ which I described in connection with my critique of Schopenhauer as “a beautiful hotel, equipped with every comfort, on the edge of an abyss, of nothingness, of absurdity. And the daily contemplation of the abyss between excellent meals or artistic entertainments, can only heighten the enjoyment of the subtle comforts offered.”

The image of the Grand Hotel hits close to home: I drafted this post in the bar of the Palazzo Sant’Angelo on Venice’s Grand Canal. Contrary to Lukács’, I don’t want to be an activist or partisan. But neither do I wish to withdraw. My goal has been to write about health and well-being from the viewpoints of empirical research and analytic moral philosophy, to write for non-specialists, and to engage policy on a longer time frame than an immediate political battle. This can only be done online: Humanity is digitally-mediated and will only become more so.*

The challenge is to find a strategy for disciplined disconnection to enhance focus, followed by selective reconnection to stay in the stream of discourse. I’m looking forward to reading Newport’s book when it comes out this week.

*This is tangential, but I can’t resist. I have been part of the internet for a long time: I began using email and Usenet (a Unix-based global discussion platform) as a graduate student in the early 1980s. In 1990, I published an article in Psychological Science arguing that scientific publishing should move to hypertext on the internet. Perhaps you think that this idea would have been obvious in the late 1980s, but not so. At the time, there were no working examples of internet-scale distributed hypertext. Unknown to me or anyone else, Tim Berners-Lee invented the World Wide Web in 1989 while working as an IT wonk at CERN. He built the first internet browser in 1990. His descriptions of this work were published in obscure places in 1992. The idea for electronic scientific publishing that competed with mine involved the delivery of journals on CD-ROMs sent through the mail. I was a programmer, but not skilled enough to build a hypertext journal, and the quantitative psychologist Peter Bentler wisely talked me out of trying. My article was ahead of its time, has attracted only 30 citations, and is forgotten. I point this out only because it was such fun to write it, and because it provides evidence that at least once, I had insight into where things were going.