I’ve fallen a bit behind, on account of being sick and having to sleep more than normal. I’ll use that as an excuse to do a quick drive-by on an interesting paper. Forgive me for not blogging in depth on it. I just can’t muster the energy. And if I wait until I have it, I’ll be swamped with other things.

Here’s how it’s going down. I’m not going to comment much on the methods. It’s an NBER working paper and I do have some questions about the methods (which reflects that I haven’t had time to think deeply about them, not that there is necessarily anything wrong with them). I’ll leave the scrutiny of methods to peer review. Until then, take all this with a grain of salt.

The Long-Term Impact of Medicare Payment Reductions on Patient Outcomes, by Vivian Y. Wu and Yu-Chu Shen:

This study examines the long term impact of Medicare payment reductions on patient outcomes using a natural experiment – the Balance Budget Act (BBA) of 1997. […] We find that […] hospitals facing large payment cuts saw increased [AMI] mortality rates relative to that of hospitals facing small cuts in the post-BBA period (2001-2005) after controlling for their pre-BBA trends. We find support that part of the worsening AMI patient outcomes in the large-cut hospitals is explained by reductions in staffing level and operating cost following the payment cuts, and that in-hospital mortality is not affected partly due to patients being discharged earlier (shorter length-of-stay).

To my eye, this paper has a terrific literature review on the relationship between hospital payment and quality/outcomes. It’s not a literature I know, so , as best I can tell, this would be a good place to start, if you’re interested.

To get at what is important about this paper, one has to recall my cost shifting posts. OK, you don’t have to recall it, because I’ll tell you. When hospital payments are cut hospitals have, broadly, two choices, cut costs or shift them. In a prior paper, Vivian Wu did the most credible analysis on cost shifting in something like the modern era, finding that hospitals shifted to private payers (insurers) 21 cents of every dollar in Medicare payment shortfall. Therefore, this paper on cost cutting is a nice companion. It gives some sense of where the other 79 cents went.

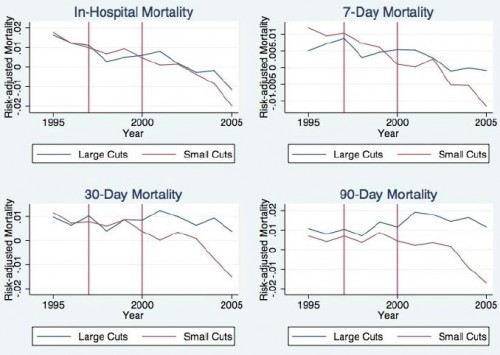

Wu and Shen begin with the following figure, which is just descriptive. Then, recognizing that hospitals are not randomized to payment levels, they ask what other possible factors could account for the difference in trends in risk-adjusted AMI mortality between hospitals experiencing large (top quartile) vs. small (bottom quartile) cuts in payments. This leads to a multivariate model in which actual changes in Medicare payments are instrumented because hospitals may respond to payment cuts in unobservable ways that affect the severity of those cuts and risk-adjusted AMI (e.g., upcoding).

Here are some of the findings:

The average Medicare revenue cut due to exogenous factors is 15% at large-cut hospitals. The coefficient estimates for this group of hospitals indicates they have 0.8 to 1.6 percentage points higher AMI mortality relative to that of small-cut hospitals. These translate to about 5% to 7% percent increase in mortality rates. Taken together, the elasticity is about -0.45, implying a 1% reduction in payment would translate to a 0.4% increase in mortality rates. The elasticity for moderate-cut hospitals in the post-BBA period is about similar around -0.38, given that the average Medicare revenue cut due to exogenous factors for this group is 8% and the effect on mortality is 3% to 4%.

When cost cutting has consequences like this, maybe we shouldn’t rejoice at low levels of cost shifting. Or maybe it’s just the payment rate changes we should think more about. By this paper, it’s not obvious those cuts led to reductions in “waste” only.

UPDATE: The original title said “two good papers.” Clearly I only covered one. I’m not going to do the other one.