As noted in my last several posts, conservative health policy analysts James Capretta and Robert Moffit have now provided one of the best available roadmaps to Republican proposals to replace ObamaCare.

I noted six critical passages that deserve attention. I’m again going slightly out of order to consider principle #5:

5. A replacement plan must be true to the Constitution and reflect a genuine federalist philosophy.

This one will take a few posts to untangle. I’ll start with some basics.

Conservative policymakers, commentators, and jurists have some stark disagreements with the way state-federal relationships have evolved since the 1960s, and perhaps since the New Deal. Many Republicans, including Mitt Romney, wish to loosen regulation of state insurance exchanges and to roll back and block-grant the Medicaid expansions embodied in health reform. Capretta and Moffit note several approaches in this vein:

The fifth key component of a genuine health-care reform plan must be an overhaul of Medicaid. Medicaid is actually three separate programs: health insurance for lower-income working-age adults and their children, health and long-term care for the non-elderly with severe disabilities, and long-term care for the frail elderly. For the purposes of replacing Obamacare, the relevant program to change is insurance coverage for working-age adults and children; the other parts will need reform as well, but should be addressed in a separate legislative effort.

They are right that the different Medicaid populations should be considered separately. When one does so, it quickly becomes apparent that basically healthy working-age adults and children are the cheapest and easiest for Medicaid to serve. It is somewhat paradoxical that these are the groups most likely and most immediately to be affected by “repeal and replace” efforts.

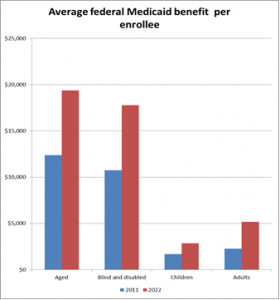

The below graph, based on figures released by the Congressional Budget Office last month, shows per-capita federal expenditures in each population in 2011 and (projected) in 2022.

Working-age adults and kids account for the majority of people receiving Medicaid. Repeal and replace efforts would prevent perhaps fourteen million people from joining the Medicaid rolls.

Working-age adults and kids account for the majority of people receiving Medicaid. Repeal and replace efforts would prevent perhaps fourteen million people from joining the Medicaid rolls.

The impact on Medicaid spending from these changes will be noticeable, but more modest than one might suppose. The aged, blind, and disabled account for two-thirds of the dollars spent on Medicaid, because each of these recipients is so much more costly. The aged, blind, and disabled also pose the greatest long-term challenges in improving the quality and economy of Medicaid care.

The main Republican urgency to quickly implement “repeal and replace” towards this population is political. Measures such as expanded coverage for young adults, limits on insurers’ medical loss ratios, and the curbing of lifetime reimbursement caps in the case of catastrophic illness or injury have already been wholly or partly implemented. These health reform provisions are part of the fabric of insurance markets, and they are popular. They can be overturned by the Supreme Court or repealed by Congress, but only at high political cost.

Right now, though, Republicans can constrain the scope of health reform by forestalling coverage expansion provisions that would be hard to repeal a few years from now as individuals and state governments become accustomed to these financial flows. As Capretta told me for a story in the Washington Monthly: “As soon as the money starts flowing, you can’t stop it.”

Curbing benefits and eligibility promised but not yet delivered under health reform is less politically costly and administratively complex than curbing benefits or addressing delivery system issues among the elderly, the blind, or the disabled. Because Medicaid’s per-recipient costs are so low for low-income adults and kids, constraining the growth of these latter groups within Medicaid cannot appreciably reduce national health care expenditures, if indeed it reduces these expenditures at all.

Capretta and Moffi also lament Medicaid’s genuine defects as a health insurance program:

Furthermore, because Medicaid pays exceedingly low fees to care providers, the program does not always offer high-quality coverage. Not surprisingly, as states have pushed physician-reimbursement levels well below the actual costs of caring for Medicaid patients, many doctors have responded by severely restricting the number of Medicaid patients they will see. The result for people on Medicaid is often a lack of accessible quality health care, precisely what the program is supposed to provide.

Advocates for Medicaid recipients and safety-net providers have spent decades seeking to raise Medicaid reimbursement levels. Many liberals, not only single-payer advocates, lament Medicaid’s status as “welfare medicine” providing a lower tier of care. The Affordable Care Act partly addresses this issue in primary care. More should be done.

Capretta and Moffit go astray in their failure to ask why states provide such stingy Medicaid reimbursements, and why in other ways this deeply necessary program is also so deeply flawed. Ironically, Medicaid’s worst defects are outgrowths of program features which the current “repeal and replace” proposals would generally make worse: Medicaid’s overly decentralized design, its over-reliance on state governments, some of whom display conspicuously tenuous commitment to the well-being of their own disadvantaged citizens, the shifting of costs and risks from the federal government onto state governments that are neither able nor willing to bear this load.

I’ll pick this up in a future post.

(HAP)