Speaker Paul Ryan wants to reform Medicaid by “block granting” the program, that is,

by capping federal funding and turning control of the program over to states. The aim of such reforms is to reduce federal funding over the long term, while preserving a safety net for needy, low-income Americans. An additional valuable aim of this effort has been to advance federalism by reducing the federal government’s role and giving states and governors more freedom and flexibility in managing their Medicaid programs and helping people in their states.

What are the likely consequences of block granting? Benjamin Sommers and David Naylor write in JAMA about how Canada’s joint federal/provincial funding of health care provides lessons about the likely consequences of block granting.

Canada is a single payer health care system. However, there isn’t a Canadian single payer. Rather, there is a single payer for each province: I am covered by the Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP). These plans are primarily funded by provincial taxes. However, provinces also receive a health transfer from the Canadian federal government, i. e., a block grant. The provincial health insurance plans are run by provincial health ministers, not the federal minister in Ottawa.

So, does provincial autonomy facilitate experimentation and tailoring by the provinces? Sommers and Naylor think not.

there is little evidence that the alleged advantages of block grants have materialized in Canada. Advocates argue that with greater flexibility and proper incentives, states can reduce costs by improving the efficiency of care. In Canada, however, the provinces’ primary means of coping with budget pressures under block grants has been to reduce funding to hospitals and bargain harder with provincial medical associations. Ironically, then, if this scenario plays out in the United States, it would exacerbate one of the chief Republican criticisms of Medicaid — that it pays clinicians such low rates that they have reduced incentives to care for low-income patients.

Indeed, physician refusal to take Medicaid patients is one of Speaker Ryan’s central criticisms of Medicaid.

What about the effects of a block grant system on federal funding of health care?

Once block funding was initiated in 1977, health care funding became a line item in the federal budget that could be arbitrarily cut or capped for fiscal or political reasons, as opposed to a level of spending pegged to the needs and health care use of the population. Importantly, these cuts occurred under both conservative and liberal federal governments.

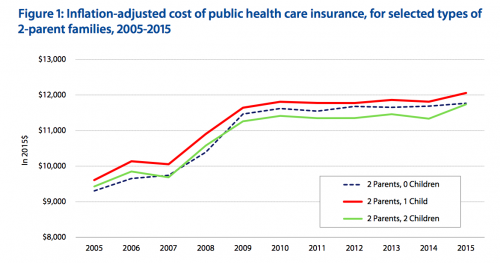

When the Canadian health transfer began, the federal government paid 50% of provincial costs. However, the transfer has steadily declined, until it is now about 20%. Sommers and Naylor predict that US federal block grants would also decline, and this is clearly one of Speaker Ryan’s goals.

However, Canadian health care spending per capita has not declined.

As the cost of providing care has risen, but the federal health transfer has stayed fixed or declined, the provinces have taxed more and the federal government has taxed less. The provincial governments hate this, because they would rather have the federal government make the unpopular choice to raise taxes. But it’s not clear whether block granting has made a big difference in the health care received by Canadians.

American states could similarly increase taxes in response to a declining federal Medicaid block grant, but would they? The key difference between Canadian public health insurance and Medicaid is that the former is universal, while the latter is means-tested. Ontarians prefer lower taxes, but if Ontario decreases funding for OHIP, every Ontarian will experience longer waits for care. But American states can cut Medicaid — and reduce taxes — without affecting the health care of better off and able-bodied citizens.

The affluent and able-bodied are also the citizens most likely to vote. American states determine their own voting procedures. Block granting gives states an incentive to manage voting so as to reduce the participation of the marginalized communities who are most in need of public health insurance. Block granting is likely to undermine the health care for the poor and disabled, and it could reinforce the post-Shelby County v. Holder efforts to restrict voting.