Have you ever seen a commercial that says, “If you have insomnia, ask your doctor about cognitive behavioral therapy” (CBT)? I haven’t. But I have seen many that urge consumers to talk to their doctors about Lunesta (Eszopiclone) or Ambien (Zolpidem) or Restoril (Temazepam) or other insomnia drug.

Does that mean the drugs are more effective than CBT? Actually, no. But they are more costly for payers and more lucrative for pharmaceutical manufacturers, generating revenue that supports expensive ad campaigns. And insomnia and other sleep problems are a huge market. About 30% of adults report some symptoms of insomnia and 10% meet all the criteria for the condition.

I’m one of them. However, instead of turning to one of the prescription drugs, I’m trying CBT. I’ll write more about my experience with it after I’m further along in the program I’m following (designed by Dr. Gregg Jacobs and recommended by my physician). For now, I want to go over some of the underlying research.

You can get up to speed on CBT by reading the Wikipedia entry on it. But it may suffice to know that its “a psychotherapeutic approach that addresses dysfunctional emotions, behaviors, and cognitions through a goal-oriented, systematic process” with the aim of “changing maladaptive thinking [that] leads to change in affect and in behavior.” In short, get right by thinking right. Obviously that’s not going to be effective for everything. But for insomnia, it is. The studies say so, and some say it’s more effective than pharmacological therapy (PCT).

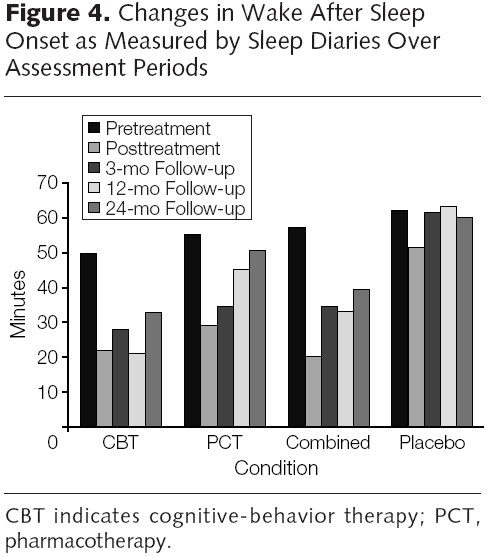

For example, in a comparative effectiveness, randomized controlled trial (RCT), Morin and colleagues compared the effects of CBT, PCT (drug: Temazepam), CBT + PCT combined, and placebo in subjects ages 55 years and older. Though they report numerous results consistent with CBT leading to longer lasting improvements in sleep than other approaches, their Figure 4 (below) provides one summary. The bars represent the number of minutes subjects were awake after sleep commenced (sleep onset), according self reports (sleep diaries).* Notice that for all follow-up intervals CBT outperformed all other approaches.

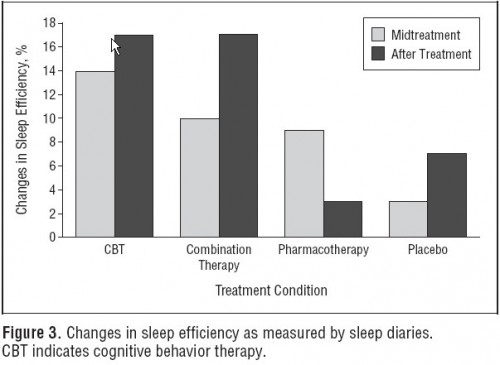

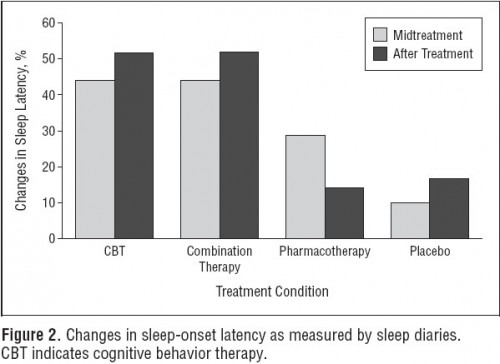

In another RCT focused on 25-64 year olds, Jacobs and colleagues found that CBT outperformed PCT (drug: Zolpidem) and placebo and was as effective as CBT+PCT combined therapy in sleep efficiency (percentage of time devoted to sleep that the subject is actually sleeping) and sleep onset latency (how long after intention to sleep the subject actually fell asleep). The charts are below.

Based on these studies, there does not seem to be any lasting advantage to PCT over CBT. I acknowledge that these are just two studies, but they are the only two RCTs comparing CBT to PCT (alone and in combination with CBT) that I am aware of. (Update: there is a third, about which I will write another time.) I will be reading other CBT studies and will likely blog on them as I do. It’s worth noting that a limitation related to the study of CBT is that a placebo is not possible, as it is for drugs. In the trials discussed above “placebo” means a drug placebo. You can’t blind the patient or practitioner to CBT.

Even with that limitation, since CBT will cost me very little and can be self-administered (and effectively so, according to another RCT), I consider it worth the effort for me. It’s cheaper and it seems to work better. Maybe fewer Americans should pop pills and more should ask their doctors about CBT for insomnia.

* The authors also show results based on objective measures of sleep, which are generally consistent with the subjective-based findings. The subjective measures (sleep diaries) are not considered inferior in this type of work because self assessment of sleep (concern about insufficient sleep) is one of the key psychological drivers of insomnia. Insomnia can be relieved in a patient who thinks he is sleeping better. Put another way, subjective improvement is improvement.