Abe Dunn, Scott Grosse, and Samuel Zuvekas are right: In many health care analyses, it is important to adjust for inflation, but there are numerous price indexes to choose from for the job. Which one should you use?

Helpfully, the authors surveyed various measures of health care price inflation and provided guidance on which to use in various circumstances. Their paper also explains why price indexes differ.

One important way they differ is the extent to which they incorporate changes in consumption patters. Laspeyres and Paasche type indexes hold fixed the quantities of goods and services consumed. The former fixes them in a base period and the latter fixes them in the current period. The only things that change in such indexes are prices. As such, they could misrepresent the actual impact of prices because people and institutions respond by changing how much of various goods and services they consume.

Put it this way, if the price of a service in the index went from $1 per unit in the base period to $1 billion per unit in the current period, consumption would fall to zero. People would substitute something else that’s cheaper. Lasperyes and Paasche indexes would miss that trend, though in different ways. The former would show massive inflationary effects because the good is in the basket in the base period, while the latter would show no inflationary effects because the good is not in the basket in the current period.

A Fisher index is the geometric mean of a Laspereys and a Paasche index. That makes it responsive to changes in consumption patterns, though not necessarily reflective of how they change period-by-period. A chained index, on the other hand, continuously updates consumption patterns.

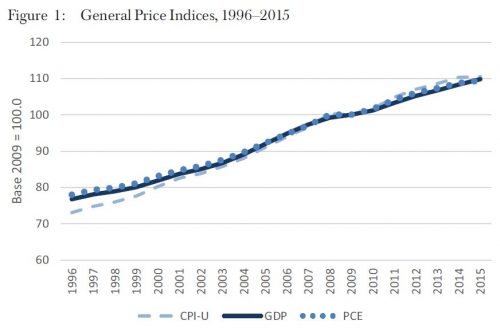

Another way price indexes differ is scope. Some indexes measure general price inflation, encompassing economic sectors beyond health care. Commonly used ones include the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), the Consumer Price Index—all urban consumers (CPI-U), and the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) index. Some details:

- GDP: A Fisher index that includes all sectors of economic activity (i.e., not just consumer spending). It is appropriate for adjusting for societal-level purchasing power changes.

- CPI-U: A Laspeyres index that captures spending by urban consumers (i.e., excluding business and government spending, as well as consumption paid for on behalf of consumers by third parties). It is appropriate for adjusting for purchasing power changes in out-of-pocket spending.

- PCE: A chained index that captures consumer spending, as well as that paid for by business, government and third parties on behalf of consumers. It is appropriate in the same circumstances as the CPI-U.

Despite the differences in how they address consumption changes and scope, these three indexes of general price inflation track one another relatively closely, as shown in Figure 1.

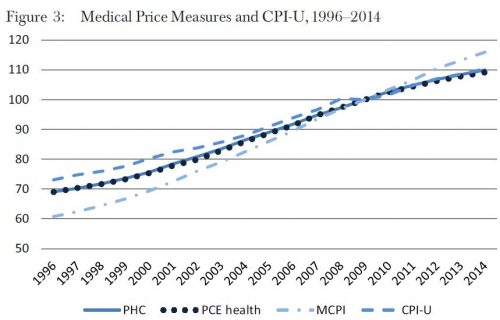

Other indexes measure only health care price inflation. These include the Personal Health Care (PHC) deflator, Personal Consumption Expenditures-health (PCE health), and the Medical Care CPI (MCPI).

Other indexes measure only health care price inflation. These include the Personal Health Care (PHC) deflator, Personal Consumption Expenditures-health (PCE health), and the Medical Care CPI (MCPI).

- PHC: A Fisher index that captures out-of-pocket and third-party health expenditures, excluding administration, research, and capital investment. It is appropriate for adjusting for general medical price changes. (Note, the National Health Expenditures (NHE) price index is an alternative that includes administration, research, and capital investment.)

- PCE health: A chained index that is otherwise nearly identical to the PHC but has a longer history.

- MCPI: A Laspeyres index designed to capture out-of-pocket health care spending, including that paid by individuals with private or Medicare Part B coverage. It is most appropriate for adjusting for out-of-pocket medical price changes.

The chart below (the authors’ Figure 3) shows the historical trends for these three indexes, alongside the CPI-U. All start below the CPI-U and then fall into line with it by the late 2000s, with the exception of the MCPI, which rises above the CPI-U. That the MCPI has a different trend than the other medical price indexes is not surprising, since it is the only one of the three focused exclusively on out-of-pocket spending.

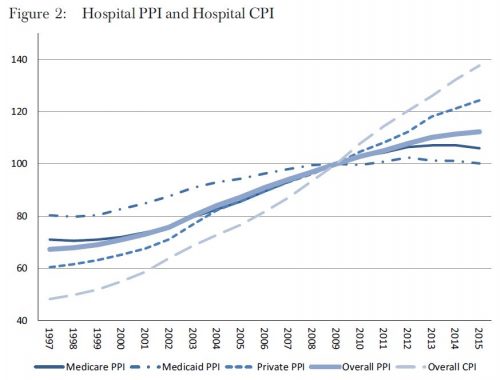

Others indexes are even more narrow, measuring, for example, hospital price inflation overall or for different payers — the Medicare Hospital Producer Price Index (PPI), Medicaid Hospital PPI, Private Hospital PPI, Overall Hospital PPI, and Overall Hospital CPI. All five of these are shown in the author’s Figure 2, reproduced below. They exist for other services as well, not just hospital care.

Others indexes are even more narrow, measuring, for example, hospital price inflation overall or for different payers — the Medicare Hospital Producer Price Index (PPI), Medicaid Hospital PPI, Private Hospital PPI, Overall Hospital PPI, and Overall Hospital CPI. All five of these are shown in the author’s Figure 2, reproduced below. They exist for other services as well, not just hospital care.

- PPI (overall and specific payers, disaggregated by service): A Laspeyres index of third-party payments appropriate for adjusting medical prices from specific payers for specific services.

- CPI (overall and disaggregated by service): The same as the MCPI discussed above, but including components for different services. These are appropriate for adjusting for out-of-pocket spending.

There are large differences in these indexes, as shown in Figure 2, reflecting differences in price growth in hospital care versus overall medical care and/or differences in growth from different payers or out-of-pocket spending. If you’re analyzing hospital payments, it’s very important to match the index to the type of analysis you’re doing and questions you’re addressing.

The authors discuss many other nuances and issues, which are beyond the scope this post. They conclude with this advice:

- To adjust health expenditures in terms of purchasing power, use the GDP implicit price deflator or overall PCE measure. The PCE measure is suitable for personal consumption. The GDP deflator is more appropriate for the societal perspective.

- To adjust overall consumer out-of-pocket spending in terms of consumer purchasing power or out-of-pocket burden relative to income, the CPI-U can be used.

- To convert average expenditures to care for a specific disease for price changes from 1 year to a different year, either the PHC deflator or the PCE health index can be used. Because of exclusions of some payers in its weights, the MCPI may not be appropriate to adjust all-payer expenditures or payments by employers, Medicaid, and Medicare Part A for medical inflation.

- To convert average consumer out-of-pocket health care expenditures from 1 year to a different year, the MCPI can be used.

- To adjust estimates of costs of inpatient services from different years, the PPI for inpatient services appears currently to be the best option.

I’m certain many published analyses do not follow this guidance, including my own. In some cases, it may matter. In offering clear guidance on how to use health care price indexes, Dunn, Grosse, and Zuvekas have provided a valuable service.