Persons with disabilities report having much poorer access to care as those without disabilities. This is true even among those with health insurance. Those are some of the findings from the latest paper of which I am a coauthor with Lisa Iezzoni and Steve Pizer. It appears in the Disability and Health Journal.

Using data from the 2000-2006 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, we examined measures of access to health care for persons with and without disabilities. We were a bit constrained by the available survey questions in defining “disability” as persistent use of assistive devices, persistent upper or lower body functional difficulty, cognitive limitations, blindness, deaf or hard of hearing.

Relative to those without disabilities, persons with disabilities are more likely to have a usual source of care. Among the insured, 91% of persons with disabilities have a usual source of care, compared to 80% for persons with no disabilities. For the uninsured, the figures are 69% and 46%, respectively. This might suggest that persons with disabilities do not have access problems. That would be an incorrect interpretation since having a usual source of care is only one measure of access. It’s also likely that persons with disabilities are in greater need of services, all other things being equal. Thus, having a usual source is, well, more usual for them.

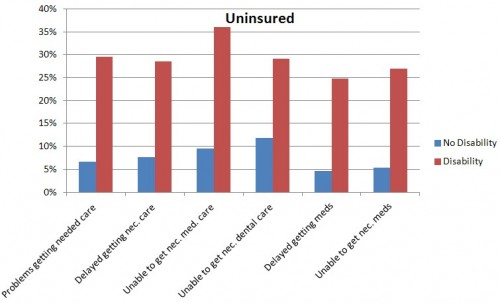

In all other measures of access to health care available on the survey, persons with disabilities had poorer access than those without. For the uninsured, that’s documented in the following figure.

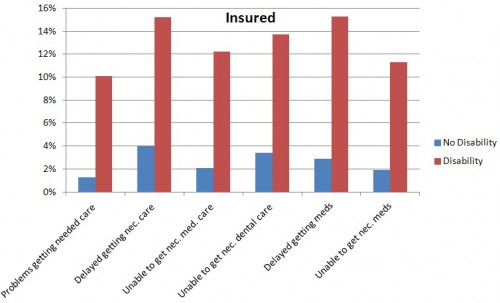

One would hope that insurance would even out access to care. Though it reduces access problems, a disparity between those with and without disabilities remains. Compare the figure above to the one below, which is for the insured (note the scales on these two figures are very different).

Why such a disparity, even for the insured? One reason is that those with disabilities may have more need for health care and, therefore, more opportunity to experience access problems. In addition, quoting the paper,

Several studies have highlighted problems relating to physically inaccessible physical examination tables and basic equipment, such as mammography machines. Recognizing these problems, Section 510 of the ACA, ‘‘Establishment of Standards for Accessible Medical Diagnostic Equipment,’’ mandates that not later than 24 months after ACA enactment, the U.S. Architectural and Transportation Barriers Compliance Board, in consultation with the Food and Drug Administration, shall promulgate minimum technical criteria for ensuring accessibility of medical equipment used in hospitals, physicians’ offices, clinics, and other health care settings. Included among these are examination tables and chairs, weight scales, mammography equipment, x-ray machines, and other radiological testing equipment. The law, however, does not explicitly mandate the use of accessible equipment.

Communication barriers pose enormous problems for persons who are deaf or hard of hearing in health care encounters. Interestingly, 62.4% of cases settled by the U.S. Department of Justice between January 2000 and March 2010 in response to complaints about disability discrimination in health care settings involved failure to provide effective communication (primarily lack of sign language interpreters). [Citations omitted in this excerpt.]

If a policy goal is to increase access to care among those that need it, providing insurance certainly is a helpful step. But there are others we could be taking, like increasing physical access for people for whom such barriers exist.